US steel baron helped found Mayo's library service

Castlebar Courthouse was the first headquarters for Mayo County Library in 1926.

A century ago last month, the members of Mayo County Council voted by 23 to five to establish Mayo’s first public library service. While the margin in favour was significant, it had taken the council quite a while to endorse the work of the Carnegie Trust, which was instrumental in the development of Ireland’s public library service in the early 1900s.

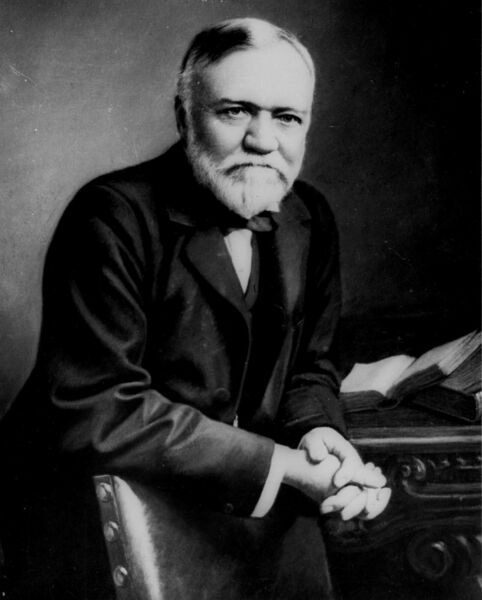

Scottish-born Andrew Carnegie (1835-1919) emigrated to the United States with his parents in 1848 and made his fortune in the steel industry in the second half of the 19th century before selling his company for an astonishing $480 million in 1901. He dedicated the rest of his life to philanthropy and one of his first acts was to donate $5.2m to New York City for the establishment of 65 branch libraries.

Carnegie was a fervent advocate for public libraries, believing they were “the best gift that can be given to a community”.

“A library outranks any other one thing a community can do to benefit its people,” he said. “It is a never-failing spring in the desert.”

Carnegie’s philanthropy was not confined to his adopted United States. Brendan Grimes, in an article in , outlines the impact of the industrialist’s largesse on Ireland.

“By early 1905, [Carnegie] had pledged $39,325,240 for 1,200 libraries in English-speaking countries, and of this money $598,000 was for Ireland. He (and his trusts) were to finance more than twice that number before the library building programme came to an end. Estimates of the number of libraries he paid for vary between 2,500 and 2,509…

“Between 1897 and 1913 he promised over £170,000 to pay for the building of about eighty libraries in Ireland. Sixty-six of the libraries were built and sixty-two of them have survived. Although the money that Carnegie gave for Irish libraries was small in proportion to his total expenditure it greatly helped the library movement in Ireland."

The Carnegie Trust built some magnificent public libraries in Dublin, Cork, Waterford, Limerick, Kerry, Kilkenny and Wicklow, but it also funded book-lending schemes in other counties, including on the western seaboard. By 1925, local authorities in Galway, Sligo and Donegal had endorsed the Carnegie Trust Scheme to fund a public library service for an initial two-year spell before handing it over to the local county council, which would impose a small fee – less than a penny in the pound – on ratepayers.

Mayo had the third largest population in the country in the census of 1926 – bettered only by Dublin and Cork – and it seemed an obvious candidate for a public library scheme, but the county council was initially reluctant to take up the Carnegie Trust’s offer of financial assistance. In the spring of 1924, councillors were asked to consider a proposal from the Trust to supply 8,000 books, valued at around £2,500, to a new public library service headquartered in Castlebar. The Trust was also willing to pay the salary of a county librarian at a rate of £250 per annum for two years.

Surprisingly, the offer was rejected by 12 votes to eight, with several opponents arguing that the new service would only benefit the people of Castlebar. Afterwards, the speculated that the library project had become collateral damage in a wider dispute in the council chamber about the increasing centralisation of public services to Castlebar under the newly established Free State. Workhouses and district hospitals had been closed in several towns in the preceding years and councillors from the rest of the county were resistant to any new project that might have its headquarters in Castlebar.

There were, however, some councillors from rural districts who were supportive of the project and chief among them was John O’Boyle, from Kilmeena, near Westport, who had worked for one of Andrew Carnegie’s companies in the United States many years earlier. O’Boyle campaigned tirelessly to get the council to reconsider its decision and managed to get the matter put back on the agenda later that year. In September 1924, the council voted by 15-11 to approve the scheme in a ballot that saw quite a few members set aside their Civil War allegiances to vote either for or against the new library. However, the scheme’s opponents managed to postpone its implementation until after the local elections in 1925, arguing that the library required a mandate from the people of Mayo.

“I am prepared to leave it to the will of the people because they are in favour of it,” remarked Patrick Corrigan, from Achill Island, who was another of the proponents of the scheme.

It was left then to the new county council – elected in the local elections in June 1925 – to decide the fate of the Mayo public library project. Just 11 of the 34 outgoing councillors were re-elected, so there was a very different dispensation in the council chamber in the second half of 1925. A new sense of urgency was also given to the project when the Carnegie Trust announced that the grants in their existing form would not be available after December 31, 1925.

In August, the new council decided to refer the matter to its Joint University Scholarships and County Education Committee, which consisted of members of the clergy, several teachers and councillors. The committee voted by 11 to three to adopt the scheme and the matter came back before the council on Saturday, November 14, for a final decision. Among the attendees was the county librarian from Sligo, where the Carnegie Scheme had already been successfully implemented.

Ironically, several of those who had opposed the library a year earlier had been re-elected and they continued to voice concerns, not just about its headquarters in Castlebar, but about the potential cost of the project once the Carnegie Trust’s funding ended and the danger of ‘immoral literature’ finding its way into the hands of impressionable young people. However, they were reassured on the final point when it emerged that the education committee had recommended the establishment of a seven-man book selection committee consisting of four members of the clergy – three monsignors and a canon, no less; clearly, there would be no fear of or any other ‘immoral literature’ getting past that particular committee.

The cost, however, was an issue that repeatedly arose during a lengthy and, at times, fractious debate in the council chamber at Castlebar Courthouse. From a vantage point of a century later, such penny-pinching may seem short sighted, but it is worth remembering that this was an era when the Minister for Finance Ernest Blythe was cutting the old age pension by a shilling a week. Rates were charged on all property owners in 1925, as opposed today when rates are paid on commercial premises alone, so small farmers in rural districts would end up footing the cost of the new library.

“It is putting our hands into the pockets of the poor people for a thing that will not benefit them,” remarked one councillor. “Bread and butter they want and not a library.”

However, others argued that the library would lift people out of poverty and give them the “mental nourishment”, as Cllr Sean T. Ruane described it, currently unavailable to the majority who could ill-afford to spend money on books. Ruane, a schoolteacher from Kiltimagh, was one of the strongest advocates for the new scheme, telling his colleagues it would be “very foolish” to turn down the offer from the Carnegie Trust. He also disputed the “insinuation” that the library would only be used by the urban-based professional classes, arguing that there was “a great demand for literature of the right type” in rural areas.

Cllr Ruane’s view was endorsed by the Sligo librarian, Mr Wilson, who noted that the demand for books in Sligo “was greatest in the Ox Mountains, and along the coastline from Sligo to Bundoran”. Dr Peter Daly, another vocal supporter of the Carnegie Scheme, said councillors were being given the opportunity to provide “valuable education for the masses”.

A proposal by the dissenting councillors to reject the recommendation of the education committee was defeated by 23 votes to five, thus paving the way for the establishment of a Carnegie Library in Mayo. By the end of 1926, a county librarian had been appointed – Dublin native Brigid Redmond – and rooms were provided at Castlebar Courthouse for the new service. Ballina Library opened in the spring of 1927, and there were soon library branches in towns across the county. In a report published in the in July 1927, Brigid Redmond noted that public libraries were now being served by voluntary workers in Westport, Ballinrobe, Balla, Ballyhaunis, Belmullet, Swinford, Crossmolina and Killala, with new ones opening all the time.

“Judging from the returns records, book hunger seems to be keener in the rural areas than in the towns,” she wrote. “There is a demand for books not only for recreation but for inspiration and for self-instruction.”

A century later, Mayo has one of the finest public library services in the country, with a magnificent headquarters in Castlebar and an excellent branch network across the county. Generations of Mayo people have benefited enormously from the outstanding service provided by Mayo County Library – and this writer certainly counts himself among them. We all owe a debt of gratitude to the councillors who had the foresight to approve the Carnegie Scheme in 1925, and to Andrew Carnegie, whose generosity and civic-minded spirit laid the foundation for today’s thriving public library service.