New book offers insight into land ownership in Kilmaine

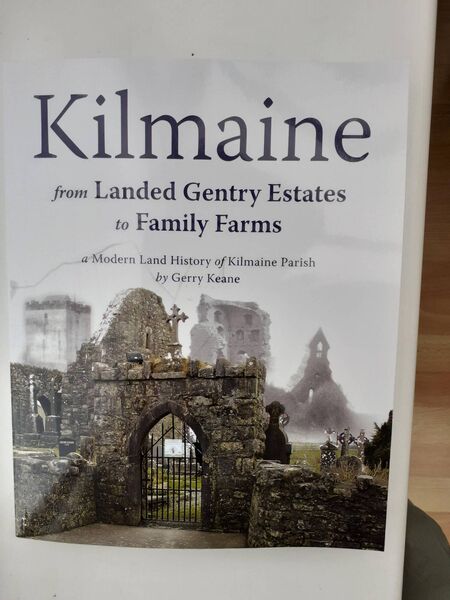

The historic Turin Castle near Kilmaine.

A new book offers a fascinating insight into the history of land ownership in a South Mayo village.

Gerry Keane's 'Kilmaine - From Landed Gentry Estates to Family Farms' has received huge acclaim since it was first published last month. The book delves deep into the shift in ownership of land in Ireland in the early decades of the 20th century.

Up to the turn of the 20th century, practically all Kilmaine land was owned in large estates by landlords of mainly Anglo-Irish background. About two-thirds of the land was rented to tenants in predominantly small holdings (5 to 15 acres). The remaining one-third was retained by the landlords for their own use or was rented to graziers on the 11-month system.

Graziers were large drystock farmers who rented land for grazing. They mostly farmed it themselves but they sometimes sublet portions of it to tenants who struggled to survive on their existing small holdings. This system of land tenure had lasted for so long that no one could envisage it changing. Yet, in less than 30 years, the ownership of all Kilmaine land transferred from the landlords to the occupying tenants. Some landlords remained put and continued to farm much-reduced acreages but most departed, mainly to England but in some cases to African countries then in the British empire.

Land transfer from landlords to tenants happened in a number of different ways. On a few estates, the tenants purchased their tenancies directly from the landlord using loans provided under the Land Acts. This method of land reform was only viable where tenants already had economic holdings, which was rare in Kilmaine. To create economic holdings the land previously owned by the landlords together with that let to graziers was used to enlarge tenants’ existing holdings. Thus land reform in Kilmaine generally involved either the Congested Districts Board (CDB) or the Estates Commissioners (acting for the Land Commission) purchasing entire estates including the landlords’ demesnes and the grazing farms for ‘striping’ amongst the existing tenants.

Severe as congestion (many small uneconomic holdings) was in Kilmaine, it was even worse elsewhere so a number of untenanted Kilmaine estates were reserved for migrants from severely congested areas elsewhere in Mayo. An unforeseen consequence of this was a shortage of graveyard space as the existing graveyard was at capacity. The local landlord was willing to provide land for a new graveyard but some of his tenants objected. They were campaigning to have his estate striped and didn’t want any land removed from the estate that might reduce the size of their striped holdings. The impasse was eventually resolved and the new Kilmaine graveyard was established.

Many Kilmaine landlords did not live on their Kilmaine estates so Kilmaine did not have many ‘big houses’. Some Kilmaine landlords lived in adjacent areas (Bowen, Ruttledge, Lindsay Fitzpatrick in Hollymount, Knox in Ballinrobe, Tighe in Ballinrobe and Scardaune. Lord Kilmaine in The Neale, Lewin in Castlegrove, Blake in Towerhill, etc.). Others lived in Laois (Staples), Galway (Costello), Rosturk Castle (Vesey Stoney) and the Isle of Man (Cromie).

The book has three sections, 27 chapters and 357 pages. Section 1 defines and describes the present-day parish of Kilmaine – an amalgamation of three civil parishes, Kilmainemore, Kilmainebeg and Moorgagagh. The townlands comprising Kilmaine parish are listed and mapped. In Section 2, each landed estate is described showing the townlands comprising it and listing the tenants who farmed the land over the years. In Section 3 the history of some of the larger estates is summarised together with some significant events during the period of land reform.

The book is available in all local bookshops.