We waste so much time worrying about ageing

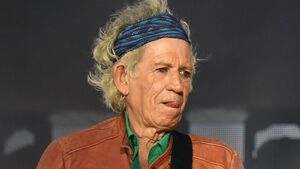

The difference between Keith Richards and those desperately clinging to youth is that Richards has embraced his decrepitude with such enthusiastic abandon that it has transformed into its own peculiar beauty. Picture: Boris Horvat//AFP/Getty Images

There's something terribly evasive about our relationship with ageing. We acknowledge it with the same stoicism we reserve for discussions about taxes, the weather, and the inevitable annual defeat of our Mayo football team. "Memento mori," whispers the dermatologist as he injects enough toxin into your forehead to fell a small village of enemies. Remember, you must die, but perhaps not look it until the very last moment.

There was a time when I consumed whatever treats a stocked fridge might offer me, staring mortality square in its bloodshot eyes before reconsidering when faced with the precipice of an early demise. Now, I scrutinise my reflection with the same forensic intensity I once reserved for kitchen cupboards, counting the creases that map my journey from there to here.

I was reminded of this temporal tyranny during a recent trip to the fashionable climes of Dublin's thoroughfares. I spied women, and increasingly more men, of indeterminate vintage with embalmed faces stretched so taut that closing their eyes seemed improbable.

Flush with money and indulgence, they've doubtless returned from some fashionable spa retreat, which involved being buried up to the neck in mineral-rich mud while drinking the purified urine of Himalayan goats, all for the bargain price of what might feed a small African nation for a month. They inevitably look terrible, but expensively so.

The anti-ageing industry - that gloriously optimistic cathedral of denial - promises salvation through serums and supplements, through creams that cost more per ounce than vintage champagne. We are told with evangelical certainty that boyish good looks need not fall by the wayside if only we submit to their rituals of retention and restoration.

My untidy and messy bathroom cabinet is a graveyard for half-used potions purchased during moments of existential panic. Small jars with promises larger than their contents, each bearing clinical-sounding names that suggest they were formulated by scientists rather than marketers.

"Cellular Regeneration Complex" one proclaims as if my skin cells might spontaneously declare independence and form a parliamentary democracy if only given the right topical encouragement.

What's fascinating isn't our collective terror of ageing but rather the intellectual contortions we perform to avoid confronting it. We've rebranded "getting old" as a disease that requires intervention rather than the fundamental condition of having survived. Scientists in white coats speak gravely about "epigenetic changes" and "cellular noise" – poetic metaphors for the cocktail party of life growing louder until you can no longer hear the conversation.

I watched a lecture on YouTube by one of those prophets of prolonged youth, a man whose own face betrayed a suspicious immobility at odds with his animated hands. He spoke at length about mitochondrial function and telomere length, using words that sounded as if they'd been invented specifically to confuse the audience into submission. "Cellular senescence," he declared with the gravitas of Moses delivering commandments, "is not inevitable." The crowd - mostly wealthy individuals with nothing better to spend their money on than the possibility of more time to accumulate more wealth - nodded sagely as if they understood a word of it.

Spouting their empty promises of turning back biological clocks, the beauty clinicians of this lucrative industry are selling the same snake oil that has lubricated human hopes since time immemorial, just with better advertising. Their ultimate product isn't youth; it's the tantalising possibility that death might be optional, at least for the moneyed who can afford the subscription fee.

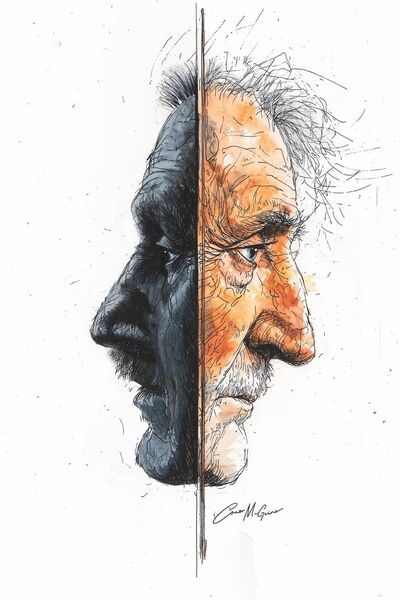

These immortality merchants fail to grasp that a face without lines is a book without text or an author. The crow's feet, laughter lines, and furrowed brows are maps that tell of battles won and lost, jokes shared, and griefs endured and transmuted into understanding.

They're not imperfections to be erased but evidence of having properly participated in the messy business of living. My words on the page dance before me with confrontational swagger, and so should my face in the mirror - cocky and strutting when observing the ravages of time.

There is something unexpectedly offensive, true, about ageing – the perfect formula for self-deprecating humour if we could just remember the punchline. The awful reality is unavoidable, while the defiant are busy injecting, restricting, and lamenting, time continues its inexorable march. The real tragedy isn't ageing; it's wasting what little time we have worrying about it.

Consider the sun worshipper with their leathery complexion, the smoker with their etched lines radiating from pursed lips, and the drinker with their gin-blossomed nose. These aren't failures of preservation but testaments to appetites indulged, pleasures savoured. Each wrinkle is a souvenir from a moment when living took precedence over preservation.

I know a few rugged seafarers who've spent years sailing the coasts of Mayo with nothing but cigarettes, booze, stiff breezes and reflected sun for company. Their faces inevitably resemble a well-used leather glove, and their voices have the texture of gravel being dragged over concrete. They have precisely two expressions: squinting against the sun and squinting against everything else.

The Saudi-backed 'Hevolution' Foundation – now there's a name that conjures images of people evolving into oil wells – claims to be pumping billions into ageing research. But what they're really funding is our collective delusion that we might somehow negotiate better terms with the universe.

Our time could be better spent cultivating the art of ageing disgracefully. After all, isn't there something infinitely more appealing about a face that bears witness to its excesses than one frozen in a perpetual state of bewildered surprise? The difference between Keith Richards and those desperately clinging to youth is that Richards has embraced his decrepitude with such enthusiastic abandon that it has transformed into its own peculiar beauty.

The Saudis talk of "healthspan equity" with the conviction of the recently converted, while their population suffers from heart disease and diabetes at alarming rates. Perhaps before funding research into the fundamental biology of ageing, they might consider addressing the fact that in parts of the region, smoking remains as common as prayer. But I suppose it's easier to write checks than to change cultures.

Their manifesto reads like a pharmaceutical prospectus written by someone who has just discovered adjectives like "laser-like focus", "razor-sharp" and "cutting-edge." They speak of "democratising science" while being funded by one of the least democratic regimes on earth. The irony, like their oil, flows thick and unrefined.

When my time comes to join the celestial waiting room, I'll leave behind a face that bears witness to a life not entirely wasted on sensible decisions. My epitaph should probably avoid flattery like "He looked good for his age" and instead offer the more honest assessment: "Here lies a man whose wrinkles were earned honestly - each one the receipt for a smile, a worry, or a raised eyebrow at life's absurdities."

These well-funded optimists fail to grasp that ageing isn't a condition to be cured but a privilege to be earned. Each line on my face - and there will be many more, time allowing, a veritable ordnance survey map of my journey. My face tells the story of a life that, while perhaps not always prudent, was undeniably lived.