There's no excuse for turning away refugees

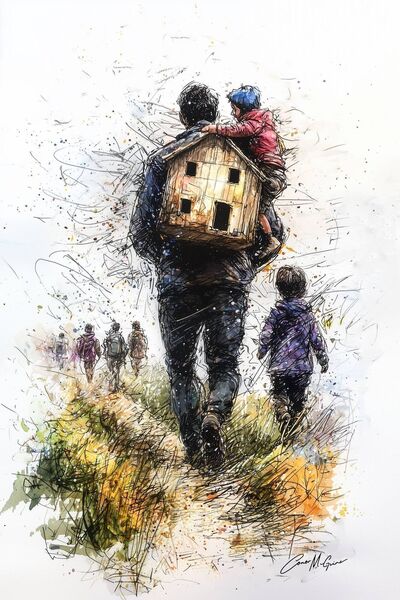

We want our refugees to be exceptional - Olympic athletes, concert pianists, cancer-curing scientists, or at least accomplished professionals - as if ordinary people fleeing extraordinary horror aren't worthy of basic human dignity. Picture: Eyad BABA/AFP via Getty Images

There's something unmistakably nauseating about watching the well-fed, centrally heated citizens of the western world wring their sanitised hands over what they insist on calling "the refugee crisis". Crisis... as if it were some passing inconvenience, like finding your favourite gastropub fully booked on a Friday night or discovering the barista has run out of oat milk for your flat white.

What we're witnessing isn't a crisis but an intergenerational reckoning, a test of that nebulous concept we've been patting ourselves on the back about for generations: civilisation. We've spent centuries congratulating ourselves on our concert halls and art galleries, literature and philosophy, and ability to create exquisite architecture and perfectly balanced educational opportunities - all while failing the most basic test of human decency.

Contrary to popular self-congratulation, being civilised isn't about creating art or building skyscrapers. Baboons groom each other, wolves care for their packs, and Paleolithic humans managed to paint rather impressive bison on cave walls without calling themselves civilised. No, civilisation is that quiet, uncomfortable moment when we choose to work against our baser instincts - against self-preservation, tribalism, and fear - to alleviate suffering simply because suffering exists.

Since World War II, we've dressed this fundamental moral principle in legal finery. We've named it "nonrefoulement" - a fancy French word for "don't send desperate people back to die". One hundred and forty-five countries signed their names to this concept, pinky-promised they'd uphold it, then developed extraordinarily sophisticated legal frameworks to wriggle out of their obligations, like schoolchildren claiming the dog ate their homework.

Ireland presents a particularly fascinating case study in collective amnesia. Our Emerald Isle - a nation whose history is defined by emigration, whose diaspora spans the globe, whose cultural identity is inextricably linked to the experience of being unwelcome strangers on foreign shores - now finds itself uncomfortable with foreigners arriving on its own doorstep.

In Dublin, Cork, and Galway, the housing crisis has reached such severity that even middle-class professionals struggle to secure affordable accommodation. When refugee centres are established in such contexts, they inevitably become lightning rods for pre-existing social tensions. This knee-jerk reaction isn't simply xenophobia; it's the predictable friction that occurs when new demands are placed on inadequate systems.

The village of Listowel recently witnessed protests when a former convent was earmarked for conversion into asylum-seeker accommodation. For concerned locals, these aren't the dramatic slants that fuel sensational headlines or political speeches, but they're the stubborn realities that define daily life in both worlds: for the villagers worried about further strain on fragile systems and for the refugee families who'll arrive to face these same broken infrastructures while carrying the additional weight of trauma, displacement, and hope.

But it is undeniably discomfiting watching the descendants of those who fled famine and persecution now raising the drawbridge.

This cognitive dissonance is equally present in our public discourse. We want our refugees to be exceptional - Olympic athletes, concert pianists, cancer-curing scientists, or at least accomplished professionals - as if ordinary people fleeing extraordinary horror aren't worthy of basic human dignity. We demand they be grateful, humble, and preferably invisible, carrying their trauma with the discretion of well-trained butlers.

Our empathy, such as it is, is tightly rationed. We can muster tears for a single drowned child on a beach but remain unmoved by statistics of thousands dying in the Mediterranean. As psychologists have argued, we are not wired to feel a million times worse about a million deaths than about one. Our moral mathematics fails on scale.

Meanwhile, our online social warriors - those keyboard-wielding vigilantes - have discovered that empathy can be weaponised with surgical precision. For every appeal to feel for drowning refugees, there's a countervailing plea to empathise with the mythical native worker supposedly displaced by immigration. These digital gladiators, fighting with metaphors and storytelling rather than facts, have created a grotesque emotional auction house where suffering is commodified and traded for paranoia.

They insist we open our hearts to the struggling pensioner in Dublin while hermetically sealing them against the Syrian family drifting on a raft of hope and desperation. It's a peculiarly modern form of emotional triage conducted by people whose experience of real suffering rarely extends beyond a poor WiFi connection.

In Ireland, this manifests in concerns about housing competition. When refugees receive accommodation while Irish citizens remain homeless, activists exploit the resulting resentment. They conveniently ignore that housing shortages predate the refugee crisis and stem from decades of policy failures rather than migration patterns.

The truth, of course, is that our treatment of refugees isn't about capacity or resources. America's obscene wealth could easily absorb millions without noticing; Ireland's Celtic Tiger economy, despite its cyclical nature, remains among Europe's most robust. For all its post-Brexit economic troubles, Britain is still one of the world's wealthiest nations. What we lack isn't capacity but will.

Yet we cannot entirely dismiss the complex security environment that shapes Western responses to refugee flows. Great power competition increasingly defines Europe's security landscape, with Russia's shadow looming particularly large. These geopolitical tensions create a context where migration inevitably becomes securitised - sometimes reasonably, sometimes unreasonably.

There's a legitimate security apparatus that must assess risks from all corners, including the possibility of bad actors moving among displaced populations. This is not merely xenophobia dressed as prudence; intelligence agencies worldwide acknowledge the potential security challenges of mass migration. Yet the magnitude of response often bears little relation to the actual risk.

The assumption that compassion necessitates naivety about security risks creates a false dichotomy that serves neither refugees nor host nations.

Perhaps we need what psychologists call "rational compassion" - objective triggers for action regardless of who's in trouble, regardless of whether their suffering makes compelling television or aligns with geopolitical interests.

Ireland could pioneer this approach by establishing clear, objective refugee assistance criteria that acknowledge humanitarian obligations and practical limitations. Rather than reactive policies driven by media cycles or emotional appeals, a framework balancing compassion with pragmatism might include transparent capacity assessments, proportional distribution of refugees, dedicated funding for integration, and regular, honest communication with host communities.

Such frameworks acknowledge legitimate capacity concerns while preventing these concerns from becoming excuses for inaction or cruelty.

Until we make these changes, however, we will continue this dance of pretend civilisation, congratulating ourselves on our art galleries, symphonies, and craft breweries while turning back boats filled with the desperate and drowning. We are, in essence, cave dwellers with smartphones, making the same tribal calculations our ancestors made, just with better public relations.

The refugee isn't seeking heroism from us. They're merely asking that we live up to our own lofty rhetoric about civilisation. They're asking us to be as good as we pretend to be. And so far, we've responded begrudgingly. Our fears - while sometimes grounded in legitimate security, infrastructure, and cultural concerns - too often become excuses for abdicating our most basic moral responsibilities.

The path forward isn't ignoring legitimate concerns about security, housing, or cultural integration. It's addressing these concerns while refusing to let them become pretexts for abandoning our humanity. It's recognising that civilisation isn't measured by the height of our buildings or the sophistication of our technology but by how we treat those with nothing to offer but their desperate need.

The question for us isn't whether we can afford to help refugees; it's whether we can afford to become the kind of people who turn them away.