The wisdom of grandparents is never outdated

There is something intrinsically fascinating about observing grandparents with their grandchildren on family outings. These intergenerational tableaux reveal more about our cultural evolution than a thousand sociological papers.

The grandparents of the war generation - those stoic, weathered custodians of privation's memory - are all but gone now. They carried themselves differently. Their economy extended beyond money to words, gestures, and expectations. They were the masters of the level gaze that could silence childish complaints at twenty paces. Their affection was expressed in plain, practical things: a bar of chocolate, money pressed into a small palm, the meticulous darning of a school jumper.

These were people who understood hunger not as a trendy intermittent lifestyle choice but as a winter companion. They had an encyclopedic knowledge of how to make meals from scraps, how to repurpose clothing, and how to stretch coal. Their wisdom was not acquired through mindfulness retreats but through the brutal university of survival.

The modern Irish grandparent is a curious hybrid: half traditional authority figure, half desperate supplicant at the altar of youth. They arrive at these family rendezvous laden with gifts, their phones filled with photos, their conversation peppered with effortful references to TikTok or Minecraft, their faces fixed in expressions of strained comprehension. They are determined to be "relevant", that most desperate of middle-aged aspirations.

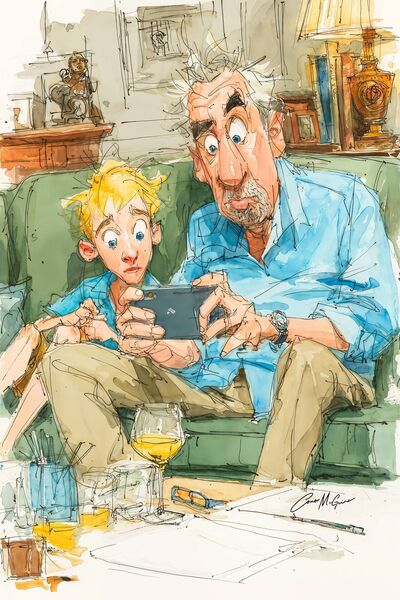

What distinguishes this generation of grandparents most starkly from their predecessors is the reversal of the knowledge hierarchy. Where once wisdom flowed downhill from age to youth like water finding its natural level, now it gushes upward against gravity's pull. The seven-year-old explains encryption to the seventy-year-old. The teenager delivers lectures on the climate crisis to the retiree who survived rationing. The toddler navigates streaming services with the nonchalant expertise of a Formula One driver while the grandparent looks on in mystified admiration.

This reversal produces its own peculiar tension. Watch carefully as the retired surgeon defers to his primary-school-aged grandson on matters of digital security, his face a complex snapshot of pride, embarrassment, and the faintest trace of resentment. His hands, which once held the literal power of life and death, now fumble through smartphone apps under the impatient tutelage of a child who has never known a world where information wasn't instantaneously available.

The war generation would have sooner gargled with broken glass than acknowledged superior knowledge in a child. Not because they were cruel or dismissive but because, in their world, wisdom was earned through suffering, patience, and endurance. It couldn't be downloaded or Googled; it had to be lived into, like breaking in a stiff pair of boots until they moulded perfectly to one's feet.

Yet there is something remarkable in how eagerly many modern grandparents embrace this inverted apprenticeship. They submit to instruction with the humble enthusiasm of novices, their reading glasses perched precariously on noses that have smelled out scarcity, recessions, and tragedy, now bent earnestly over screens being explained by voices that have not yet broken.

What we're witnessing isn't simply technological ineptitude versus digital nativity. It's a profound shift in how authority and knowledge are conferred and recognised. The grandparent who survived want with ingenuity knows how to predict rain by watching swallows, how to stretch a pound of mince to feed nine people, and how to re-wallpaper a room with wallpaper retrieved from a bargain basket. But this practical almanack of survival is as obsolete as a telegraph in an age where abundance has replaced scarcity as our defining condition.

The old metrics of competence - endurance, resourcefulness, the ability to make do and mend - have been replaced by new ones: technological fluency, the capacity for constant reinvention, and comfort with ephemeral trends. In this upturned framework, the child is sovereign and the elder a well-meaning anachronism.

Despite these changes, something timeless remains in these family encounters. Beneath the digital divide, the essential alchemy of the grandparent-grandchild relationship persists. It still exists in that privileged space outside the immediate pressures of parenting, involving the exchange of stories, secrets, and small rebellions against the middle generation's rules.

And perhaps most poignantly, both are engaged in a form of mutual tourism. The child gets a glimpse of history with a pulse and a pension; the elder gets a guided tour of a future they will largely not inhabit. Each is an emissary from a foreign country the other will never fully visit.

When the war generation grandparents dispensed wisdom, it came with the unarguable weight of experience. "Don't waste food; I've known hunger", "Don't complain about walking; I've known a time when petrol was impossible to get", "Don't take peace for granted; I've seen what happens when it disappears". Their authority came with footnotes written in privation and grief.

Today's grandparental advice comes hedged with qualifications, delivered with the tentative politeness of a guest unsure of the house rules. "I don't know if this is still how things are done, but in my day..." They are historians of their own obsolescence, curators of approaches to life that have been superseded like VHS tapes or floppy disks.

Yet something vital is exchanged in these encounters that transcends the evident comedy of their differences. The best grandparents still offer what they always have: the long view. In an age of perpetual present tense, where history has been compressed to anything before last week's viral sensation, they are repositories of perspective.

We're observing adaptation in real time – the remarkable plasticity of human relationships across generational divides. The war generation adapted to peace and prosperity while maintaining the reflexes of scarcity. Today, we are adapting to the terrors of the AI technological revolution while maintaining the reflexes of analogue communication. Each brings to the encounter their own form of emotional currency, their own metrics of care.

This refusal to calcify provides a curious bridge to their grandchildren, themselves in perpetual states of becoming. Both generations find themselves defined by fluidity in a way the more rigid middle generation often is not. Watch the teenage boy patiently explaining non-binary identity to his widowed grandmother. Her comprehension comes not from intellectual analysis but from her own recent experience of redefining herself after fifty years as someone's wife.

There's an unintentional comedy in these encounters – the clash of vocabularies, the mismatched references, the occasional chasms of mutual incomprehension. But there's grace, too, in the willingness of each to reach across decades of differing experience toward some common ground.

Different languages of care, perhaps, but recognisable translations of the same essential message: I see you. You matter to me. I am investing in your world even though it is not mine.

And in that simple, profound exchange lies the true wonder of the relationship – this bridge built between worlds that span not just decades but entire ways of being human. It suggests that despite our technological acceleration and cultural reinvention, something essential about human connection remains constant: the need to be witnessed by those who came before and understood by those who came after.

Perhaps this is the greatest gift exchanged in these encounters: not wisdom or technological know-how, but perspective itself – that most precious and elusive of commodities in an age of narrowing horizons. The long view from one end of life, meeting the fresh gaze from the other, creating something more valuable than either could manage alone.