The poorest will suffer from Trump's tariffs

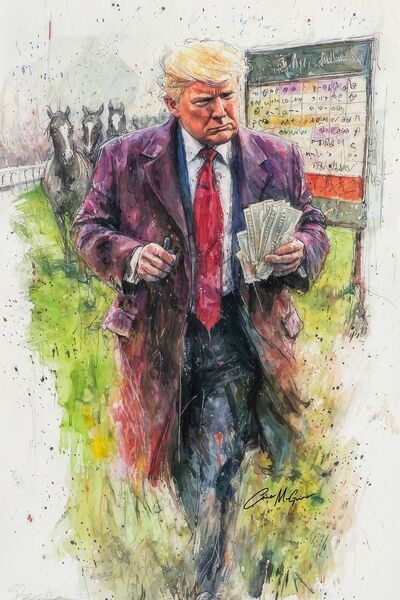

US President Donald Trump has unleashed the 'mother of all trade wars'. Picture: Andrew Harnik/Getty Images

In what can only be described as economic chest-thumping of Cro-Magnon proportions, US President Donald Trump has unleashed his latest fiscal cudgel upon the world. A 20% tariff on all European Union goods to America joins a veritable smorgasbord of punitive measures against nations Trump seems to have selected with all the careful consideration of a toddler picking a fight in preschool.

The UK, spared the full European spanking, will still face a 10% levy. One imagines the special relationship is now about as special as a participation medal at a bridge tournament. The UK government, bravely maintaining that a deal is still "possible" and "favourable", has launched a consultation faster than you can say "desperate measures". Jonathan Reynolds, with the enthusiasm of a man attempting to bail out a breached Thames barge with a teacup, assured the Commons they're keeping "every option open" while drafting an "indicative list" of potential retaliatory tariffs.

The spectre of past protectionist catastrophes looms like an uninvited guest at this fiscal feast. The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, Herbert Hoover's masterstroke of economic self-immolation, imposed tariffs of around 20% on over 20,000 imported goods. The goal was noble - protecting American farmers and businesses during the Great Depression. The result? A global trade war that made the Depression about as "Great" as it sounds.

Trump's sweeping new tariffs threaten to slash EU exports by at least €85 billion, with the automotive and food sectors bearing the brunt of this economic bludgeoning. The modern equivalent may well be a digital-age depression - one where supply chains collapse not with a bang but with algorithmic precision. What began as "America First" posturing will likely end in America Isolated, as major trading partners from China to Canada have already demonstrated their willingness to implement retaliatory measures.

In 1930, countries retaliated with their own tariffs on American goods faster than you could say "economic suicide pact". Bank failures bloomed like spring flowers, particularly in agricultural regions. What began as economic nationalism ended as international mutually assured destruction.

The 2025 version of this retaliation appears meticulously crafted. Now, with Trump unleashing what amounts to the "mother of all trade wars", we can expect surgical strikes against his support base rather than random economic bombardment.

Yet some lessons from history remain stubbornly unlearned. As the philosopher George Santayana might have said (had he lived to witness today's economic posturing): "Those who cannot remember tariff wars are condemned to repeat them, usually with greater enthusiasm and less foresight."

If American protectionism feels novel, one need only look to the British Corn Laws of 1815-1846 – tariffs designed to keep domestic corn prices artificially high to benefit landowning aristocracy. The effect was to make food unaffordable for ordinary Britons while stifling manufacturing growth by decimating disposable income.

The contemporary parallel might be Trump's determination to artificially inflate prices of everyday goods to benefit specific American industries. Just as the Corn Laws protected the landed gentry at the expense of the common citizen, today's tariffs may disproportionately benefit certain American corporations while the average consumer foots the bill through higher prices and economic disruption.

For anxious Irish exporters, these tariffs don't just represent economic theory but pose "major threats to Irish firms" with the potential to devastate the Irish economy. The scrambling EU, much like the opposition to the Corn Laws, is not taking this lying down, with responses being formulated that could escalate this economic skirmish into a full-blown trade war.

These 1815 myopic measures became the crucible for David Ricardo's law of diminishing marginal returns, laying the foundations for modern economic theory – perhaps the only positive outcome of the Corn Laws legislative folly. The laws were eventually repealed, but not before they had inflicted economic damage with the precision of a drunken dentist.

Perhaps today's trade war will similarly birth new economic theories – cold comfort for businesses caught in the crossfire of what appears to be economic policy dictated by wounded pride rather than sound fiscal reasoning.

The law of unforeseen consequences dances through economic history with the grace of a hippopotamus in ballet shoes. Trump's tariffs may aim to protect American jobs and reduce trade deficits, but they can't simultaneously achieve all their intended goals.

For tariffs to generate the predicted revenue, American consumers must absorb price increases while maintaining their purchasing patterns – buying the same Bangladeshi clothing and South Korean electronics, just at higher prices. Yet for American manufacturing to benefit, those same consumers need to switch to domestically produced alternatives - meaning less tariff revenue. It's economic quantum mechanics – you can observe the position or velocity, but not both simultaneously.

The Irish casualties in this economic Verdun are already emerging. Kerrygold butter, our grass-fed dairy darling of American consumers, now faces a competitive disadvantage against products from tariff-favored nations like New Zealand. Irish whiskey, which constitutes a significant portion of Ireland's €865 million annual drinks export to America, anticipates immediate sales impacts. The Taoiseach's assurance that Ireland will "weather this storm" carries all the conviction of a meteorologist announcing light showers during a hurricane.

Tariffs are fiscal boomerangs, thrown with precision at foreign targets only to return and strike the thrower with unanticipated force. When New Zealand attempted extreme protectionism before opening its economy in the 1980s, importers would purchase finished television sets, disassemble them, and then reassemble them to qualify as locally made, finding this Byzantine process cheaper than paying tariffs or manufacturing from scratch. The economic distortion created absurdities that would make a comedic playwright proud.

The European response remains measured for now. France's government spokesperson, Sophie Primas, declared, "We are ready for this trade war," with the enthusiasm of someone preparing for bowel surgery. The EU promises to "protect business" while avoiding escalation, though targeting American tech giants like Meta, Google, and Apple remains an option should diplomacy fail.

Lost in the diplomatic sabre-rattling is the silent victim – the consumer. Tariffs invariably transform into inflation, reduced product choice, and economic stagnation. As JP Morgan's David Kelly eloquently put it: "The trouble with tariffs, to be succinct, is that they raise prices, slow economic growth, cut profits, increase unemployment, worsen inequality, diminish productivity and increase global tensions. Other than that, they're fine."

The Tánaiste Simon Harris called the move "pretty darn stupid from an economic point of view" – a statement displaying both remarkable restraint and economic literacy. He warned against the EU deploying its "nuclear option" of service tariffs, which might impact Ireland's tech sector.

The bitter irony is that free trade when conducted in a truly competitive environment benefits everyone. But our EU political overlords, long jealous of our tech Golden Goose, urged on by continental industry lobbyists, have apparently decided that mutual prosperity is less exciting than reciprocal punishment.

As we face this brave new world of economic nationalism, one can't help but recall that the introduction of the Corn Laws benefited the top 10% of income earners in the United Kingdom while causing hardship for the bottom 90%. Perhaps therein lies the answer to why, despite centuries of economic evidence, protectionism remains stubbornly popular among certain political classes.

The race to the bottom has begun, with nations introducing defensive tariffs like medieval kingdoms building higher walls. – "History is a teacher of life" – but only to those prepared to listen. In the cacophony of economic posturing, it seems few are willing students.