Rural midwives: the unsung guardians of their day

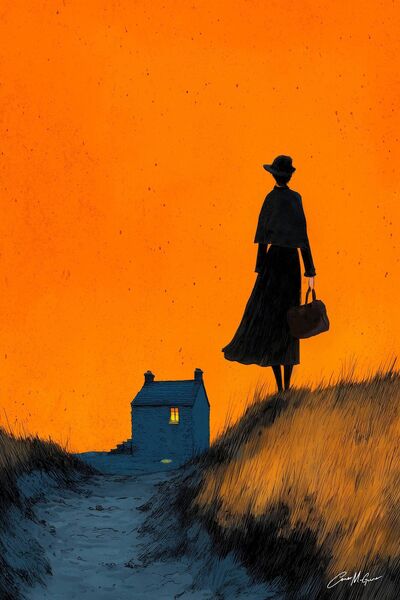

Mary Anne Fanning's midwifery bag dating from 1898.

In the shadow of the round tower, where history whispers through the corridors of Turlough Park, a leather bag tells a story that would make the most hardened cynic pause for breath.

The National Museum of Ireland's Country Life at Castlebar has become an unlikely shrine to one of the most profound yet overlooked chapters in Irish social history. Here, amongst the usual suspects of agricultural implements and domestic curiosities, sits Mary Anne Fanning's 125-year-old midwifery bag, a repository of miracles and tragedies that speaks to something far more elemental than mere medical practice.

Fanning, who worked as a district midwife and nurse in Co Kerry and then in Co Dublin for 48 years in the first half of the 20th century, represents a vanishing breed of rural Irish women whose very existence challenges our contemporary understanding of female agency in what we lazily assume was an oppressive patriarchal society. Her exhibition, running until July 2025, forces us to confront an uncomfortable truth: that long before the apparatus of modern healthcare descended upon rural Ireland, there existed a parallel universe of female authority, knowledge, and power that operated entirely outside conventional historical narratives.

The midwife's bag itself - cracked leather worn smooth by countless urgent journeys across Kerry's unforgiving landscape - contains instruments that seem almost medieval to our sanitised sensibilities. Yet these tools delivered thousands of Irish children into the world when hospitals were the preserve of the urban elite and death in childbirth remained a stark reality rather than a statistical abstraction. Fanning's career spanned nearly half a century, taking her from the poverty-stricken cottages of Kerry to the more genteel confines of Garristown in Dublin, where she attended to rebels during the 1916 Rising, a detail that adds revolutionary flavour to what might otherwise seem a conventional tale of female service.

But to reduce these women to mere servants of the community would be to fundamentally misunderstand their place in Irish society. The country midwife occupied a unique position in the social hierarchy - neither fully respectable nor entirely marginal, wielding intimate knowledge of bodies and births that granted them a form of authority unavailable to other women of their class. They were the keepers of secrets, the arbiters of life and death, and crucially, the only medical professionals most rural Irish families would ever encounter.

The tension between these traditional "handywomen" - as they were sometimes dismissively called - and the emerging medical establishment provides a fascinating subplot to Ireland's broader story of modernisation. Lady Dudley's Scheme, implemented in 1903, brought trained nurses to the remote western counties, creating an often bitter rivalry between local knowledge and institutional authority. One nurse's report from 1910 captures this friction perfectly, describing a confrontation with a "handy woman, who is a great scold" who had to be removed before professional care could be administered to a woman giving birth in what the nurse described as "an old stable".

These reports, steeped in professional disdain, expose the class warfare beneath the veneer of medical progress. The sneering dismissal of traditional birth attendants betrays something more profound than concern for standards - it reflects genuine terror at women who answered to no institution, who wielded authority derived from skill rather than certificates. Here were practitioners who had absorbed their knowledge through years of attending births, watching, learning, failing occasionally and succeeding mostly - an entirely different epistemology that made bureaucrats and medical boards profoundly uncomfortable.

The folklore surrounding Irish midwives suggests powers that transcended the merely medical. Stories persist of midwives who could transfer the pain of labour from woman to man - a piece of vernacular justice that speaks to both the mystique surrounding their profession and the community's recognition of their special status. Whether such tales reflect the genuine belief or represent a kind of collective wishful thinking matters less than what they reveal about how rural Irish society understood female power and authority.

Mary Anne Fanning's story intersects with broader currents in Irish history that extend far beyond the delivery room. Her attendance on Thomas Ashe and other 1916 rebels reminds us that the intimate and the political were never truly separate spheres. Birth and death, the domestic and the revolutionary, the sacred and the secular - all these supposedly distinct categories collapsed in the face of human need and the midwife's calling to respond to it.

The exhibition includes a christening gown from 1902 that Fanning herself sewed, still in use by her family today - a tangible link between generations that speaks to continuity and tradition in ways that political narratives often miss. This simple garment passed down through children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren, represents a form of cultural transmission that operated independently of formal institutions, creating bonds of memory and identity that state-sponsored nationalism could never quite capture.

The poverty that characterised much of rural Ireland during Fanning's career adds another dimension to her story. Working in houses without running water, electricity, or sometimes even proper beds, these midwives improvised constantly, making do with whatever materials came to hand. The conditions they encountered - patients lying on tables or straw mattresses, births taking place by candlelight in single-room cottages - would appall modern sensibilities, yet somehow, these women managed to bring thousands of children safely into the world.

We cannot know precisely how many mothers and babies these women saved, but the evidence suggests their record was extraordinary, considering they worked without antiseptics, electricity, or backup. Their success stemmed from something hospitals were rapidly forgetting - that birth belongs to women, not doctors. As city hospitals began treating labour like a disease requiring aggressive treatment, rural midwives held fast to an older wisdom that saw pregnancy as fundamentally normal, something to be shepherded rather than conquered.

When traditional midwifery finally surrendered to medical orthodoxy, Ireland lost far more than a profession - it witnessed the dismantling of an entire way of understanding who could know what. The new state, flexing its institutional muscles after independence, systematically replaced informal women's networks with formal male hierarchies. What vanished was not just midwifery but a parallel universe where female authority had flourished independently, beyond the reach of church or state approval.

The timing of this exhibition feels pointed. Just as modern women increasingly reject the conveyor-belt approach to childbirth, questioning why perfectly healthy pregnancies require intensive medical management, Mary Anne Fanning's story resurfaces to remind us that such scepticism has deep roots. Her battered bag arrives at Castlebar precisely when women are rediscovering that birth worked perfectly well for millennia before obstetrics decided otherwise. Mary Anne Fanning's story suggests that such questioning has deep historical roots and that the tensions between professional authority and personal autonomy are neither new nor easily resolved.

Turlough Park's decision to celebrate Fanning feels long overdue - a belated nod to women who've been airbrushed from the national narrative with suspicious thoroughness. These midwives were hardly wallflowers waiting for history to happen around them. They held life and death in their weathered hands, making split-second decisions that shaped entire family trees across rural Ireland. What they left behind reaches well beyond obstetrics - networks of women supporting women, knowledge passed hand to hand, courage exercised without fanfare or expectation of glory. Their achievements deserve to stand beside the poets and politicians we typically celebrate.

In an age when expertise is increasingly contested and traditional knowledge dismissed as superstition, Mary Anne Fanning's battered leather bag offers a different model - one where authority derived not from credentials but from competence, where power emerged from service rather than status, and where women found ways to carve out spaces of influence even within deeply patriarchal societies. Her story reminds us that progress is never simply linear, that modernisation always involves loss as well as gain, and that the most critical chapters in human history are often written by those whose names we never learn to pronounce.