Priest's tragic death is a challenge to us all

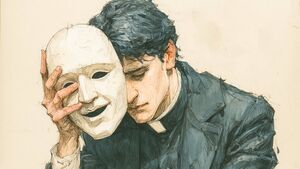

Fr Balzano's tragedy strips away the ecclesiastical veneer to reveal what we'd rather not acknowledge: that beneath the Roman collar beats a heart no less fractured than our own. Illustration: Conor McGuire

On Saturday, July 5th, 2025, in the quiet parish rectory of Cannobio, overlooking the serene waters of Lake Maggiore, Fr Matteo Balzano reached a conclusion that defies our understanding. At the age of 35, this priest who had chosen a life of service in one of Italy's most beautiful corners, where ancient churches nestle against alpine landscapes and the rhythms of parish life follow the seasons of both liturgy and lake, took his own life.

What led him to that final, irreversible moment remains hidden within the privacy of his own struggle - a struggle that reminds us that even those called to minister hope can find themselves overwhelmed by forces we cannot fathom. His death confronts us not with easy explanations but with the mystery of human suffering that respects neither collar nor calling. His death has left the parish reeling, but it shouldn't surprise anyone who's been paying attention to what's happening to priests across Ireland and beyond.

When a priest ends his life, it breaks something fundamental in how we think about faith. We expect these men to be repositories of hope, dispensers of comfort, the ones who show up when everything else falls apart. But Matteo's death exposes an ugly truth: the people we rely on for spiritual strength are sometimes the ones most desperately in need of it.

The priesthood is built on a contradiction. Priests are simultaneously the most visible people in their communities and the most isolated. They stand before congregations every day, officiate at weddings and funerals, and get called out for midnight emergencies. Everyone knows them. Nobody really knows them.

This wasn't always the case. For generations, priests occupied a clearly defined social position. People might not have been friends with their priest, but they knew where he fit in the community hierarchy. That distance was limiting, but it also provided a kind of structural support. The priest had his role, parishioners had theirs, and everyone understood the boundaries.

Those boundaries have collapsed. The abuse scandals didn't just damage the Church's reputation - they left individual priests carrying the psychological burden of historical institutional failure. A priest today might walk into any room wondering if people are looking at him with suspicion rather than respect. That's a corrosive way to live.

The practical realities make everything worse. Vocations have dropped through the floor. The average Irish priest is pushing seventy. Young priests find themselves managing multiple parishes, juggling pastoral care, administrative work, building maintenance, and parish politics while trying to maintain some semblance of spiritual life.

People always bring up celibacy when discussing priestly loneliness, as if getting married would solve everything, but that misses the real problem. It's not about lacking a wife and children. It's about inhabiting a role that society increasingly doesn't understand or value. A married priest might still feel profoundly isolated if his fundamental purpose has been eroded.

Consider the difficulty of what we expect from priests. They're supposed to counsel couples on marriage while never having been married. They advise parents while having no children. They're meant to understand worldly success while having renounced material ambition. They comfort the grieving while their own grief - for departed loved ones, for the declining Church, for their own sacrificed possibilities - goes largely unacknowledged.

The Irish context adds particular complications. Many priests still live in supportive arrangements, sharing presbyteries with colleagues or living in religious communities where shared meals and conversation provide natural buffers against isolation. Despite broader cultural shifts, many Irish Catholics continue to sincerely appreciate their priests, creating pockets of genuine relationships that sustain many clergy during difficult periods.

But the support is wildly uneven, as some priests thrive within caring communities while others find themselves stranded in parishes where their presence feels like a reminder of scandal rather than a source of comfort. The contemporary Irish priest experiences constant whiplash, moving between communities of genuine appreciation and contexts where he feels more like a scapegoat than a shepherd.

Something unexpected has emerged from this crisis. The priests who remain, especially those who entered the priesthood recently, have chosen their vocation with full knowledge of its difficulties. They represent a purified calling, stripped of the social privileges and cultural respect that once made priesthood an attractive career path. What remains is closer to the original Christian witness: a radical commitment to service that makes little sense by worldly standards.

The most effective responses to priestly loneliness haven't come from church hierarchies but from grassroots initiatives. Priest support groups, modelled on everything from AA to book clubs, provide spaces where men can acknowledge their struggles without compromising their authority. Others use technology to maintain connections across vast rural parishes.

Such well-intended initiatives point towards a broader truth, perhaps suggesting the solution isn't to radically change the priesthood but to quietly reimagine it so it becomes fit for purpose. The stilted model of the multitasking priest, heroically managing his parish single-handed, is no longer a viable reality. We are envisioning priests as part of wider teams, including laypeople, deacons, and religious sisters, where responsibilities are distributed among those best equipped to handle them.

This shift makes theological sense. Only priests can consecrate the Eucharist, absolve sins in confession, anoint the sick, and perform the sacred rites that form the irreplaceable heart of Catholic worship.

Here's the thing about having fewer priests: it's actually liberating. For generations, we've turned these men into glorified middle managers, drowning them in account books and building maintenance when they ought to be doing what they trained for - consecrating bread, absolving sins, and anointing the dying. It's like asking Pavarotti to tune the orchestra's instruments. The shortage forces a brutal clarity: let priests be priests, and find someone else to balance the books. Revolutionary stuff, obviously.

Fr Matteo's tragedy should serve as a wake-up call for Catholic communities everywhere. Too often, less committed parishioners treat their priests as spiritual service providers rather than fellow travellers on the Christian journey. They demand availability without offering friendship, seek comfort without providing support, and expect perfection while forgetting that their pastor needs salvation as much as anyone else.

The most profound lesson from this episode is that the Church's mission of accompaniment - walking alongside those who suffer - must extend to its own ministers. The priest who comforts the bereaved needs comforting. The confessor who grants absolution needs forgiveness. The shepherd who protects the flock requires protection himself.

The loneliness of our priests reflects a broader spiritual crisis in our culture, an age of unprecedented connection yet epidemic isolation, where traditional communities have fragmented and ancient sources of meaning have been discredited. The priest, standing at the intersection of the sacred and the secular, bears the full weight of this cultural transformation.

A priest taking his own life shouldn't be seen as evidence that priestly celibacy must be abandoned or that the institutional Church is beyond reform. It should remind us that the ministry of presence - simply being with others in their struggles - is perhaps the most radical act possible in our disconnected age. But for that ministry to continue, those who practice it must themselves experience the grace of being truly seen, truly known, and truly loved by the communities they serve.

Fr Balzano's tragedy strips away the ecclesiastical veneer to reveal what we'd rather not acknowledge: that beneath the Roman collar beats a heart no less fractured than our own. The priest who absolves our sins wrestles with the same midnight terrors, the same gnawing questions about whether any of this matters. We've demonised and sanctified our clergy by turn, then wondered why they prove so disappointingly mortal.

Death settles accounts with brutal honesty. Those who devoted themselves to purposes beyond their own comfort deserve better than our crude mythology - neither the convenient scapegoats for historical institutional failings nor the bloodless icons we chisel from stone. They were men who chose difficult paths, who stumbled and doubted and persevered anyway. Their humanity was not a flaw to be airbrushed away but the very thing that made their service meaningful. We diminish them when we reduce them to caricatures of corruption or sanctity. Better to remember them as they were: mortal, fallible, and worthy of our respect.