Preparing for the inevitable next pandemic

Belmullet in lockdown in 2020. Picture: Tom Reilly

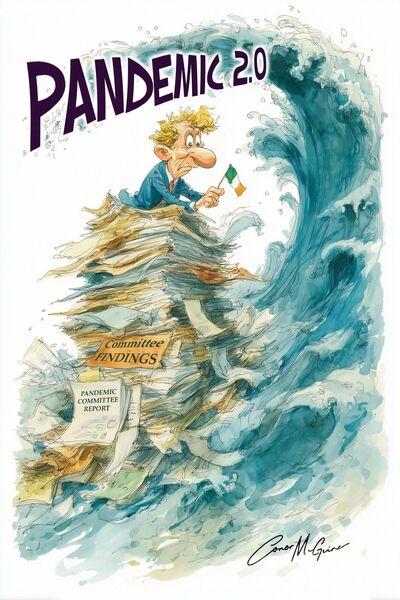

As the rapids of Covid-19 fade into memory, is Ireland truly ready for the next deluge? Where do we stand on pandemic preparedness as an administration is still drying off from the last flood?

There's something inherently Irish about our approach to catastrophe – a peculiar blend of fatalism, flexibility, and that uniquely Celtic capacity to follow the rules while silently questioning their wisdom. We endured Europe's longest lockdown with the stoicism of medieval monks, only occasionally slipping out for illicit pints when the self-flagellation became too much to bear.

The narrative arc of our Covid saga reads like a Yeatsian poem – full of beauty and terror, rich with metaphor, occasionally sublime, and frequently baffling. We were "battening down the hatches" and "riding waves" while our politicians spoke of "flattening curves" and "following science" with the uncertain conviction of altar boys reciting Latin without comprehension.

In September 2023, with chastened post-pandemic grimness, then Minister for Health Stephen Donnelly announced with characteristic bureaucratic fanfare that Ireland would appoint an expert to design a "new emerging health threats agency". One could almost hear the rustle of civil service papers and smell the fresh paint on another government edifice. Ireland planned to build "on existing assets and infrastructure" – that delightful euphemism for "making do with what we've already got" – to focus on infectious diseases and pandemic preparedness. What became of this avowed intention I do not know, despite some research on the topic.

The great Irish tradition of establishing committees to study the establishment of further committees continues unabated.

Professor Hugh Brady, chairman of the Public Health Reform Expert Advisory Group and president of Imperial College London, kindly informed us that Ireland performed rather well during the Covid-19 pandemic. Our excess mortality was comparatively low and our vaccine uptake was enviably high. Irish people are good at being told what to do when sufficiently frightened. It's one of our more endearing colonial hangovers, so well done to one and all and condolences to the myriad of deceased.

What the report doesn't capture is the peculiar texture of the Irish lockdown – the way we transformed cocooning into a competitive sport, the WhatsApp groups blooming like spring flowers as neighbours coordinated grocery deliveries for the elderly, the ritual evening applause for healthcare workers that made us feel marginally less useless as we sat in our pyjamas grimacing through yet another Zoom meeting.

Ireland's pandemic management resembled one of those meandering Irish drives through winding country roads – replete with surprising vistas, frequently terrifying, and somehow arriving at the destination despite - rather than because - of the navigator's instructions. We zigged when others zagged. We masked when others were bare-faced. We closed pubs when others merely limited capacity.

What's most intriguing about our approach to future pandemic preparedness is what remains unsaid. The report acknowledges with admirable understatement the "mental health issues" that emerged from our prolonged isolation – the "worrying levels of loneliness" and "post-traumatic stress symptoms". What it doesn't capture is the way Irish society became both more atomised and more cohesive simultaneously – neighbours who hadn't spoken in years exchanged observations over garden walls, while family members a county away became strangers.

The economic impact receives a similar understatement. The Covid-19 Pandemic Unemployment Payment cost a mere €9.2 billion, a figure tossed out with the casual indifference of someone ordering a round at closing time. What price can we put on lost businesses, closed restaurants, and the elderly dying in futile isolation? Even the most numerate accountant would struggle to calculate the whole ledger.

Our government's approach to future pandemic preparedness has all the urgency of a man contemplating life insurance while being administered the last rites. Since 2021, we've filled 40 consultant posts in public health medicine, with 242 staff hired under the public health reform programme – numbers that sound impressive until one considers the vastness of what we're preparing for.

In office until May 2024, Professor Breda Smyth, the Chief Medical Officer, noted with scientific precision that we must be prepared for "Mpox, Ebola, Marburg disease, and the evolving threat of avian influenza". One wonders if there's a government bingo card of potential apocalypses, with civil servants marking them off over coffee and biscuits.

What's fascinating is how we've transformed pandemic management into a peculiarly Irish inertia, like lamenting the shortening days of late autumn or complaining about the weather. We've become connoisseurs of isolation, experts in restriction. During Covid, we embraced the guidelines with the fervour of religious converts, occasionally peering through twitching curtains to tut-tut at neighbours hosting illicit gatherings of six.

One recommendation in the report suggests having "a more strategic plan to protect society's most vulnerable people". One might reasonably ask why such a plan wasn't already in place. The nearly one-third of Covid deaths occurring in nursing homes represent not just a statistical footnote but a moral failing of spectacular proportions. Our elderly, sequestered from family and friends in their final moments, paid the highest price for our unpreparedness.

The report also called for "a robust communication plan including localised information to prevent 'pandemic fatigue". How charmingly optimistic. It is as if the problem with government pandemic communications was merely one of frequency rather than clarity. Recall the delightful confusion of the five-level restriction system that seemed to possess more sub-clauses than the Maastricht Treaty.

The proposed new agency will (or is?) presumably be housed in a Dublin office block, staffed by earnest professionals with advanced degrees and substantial experience in committee sitting. They will produce reports of exquisite thoroughness, filled with actionable recommendations that will sit on ministerial desks like unwanted Christmas fruitcakes.

What's needed isn't another bureaucratic superstructure but rather a fundamental rethinking of how we approach the collective crisis. The Covid experience revealed Irish society's strengths and weaknesses – our capacity for solidarity alongside our institutional fragility.

The Irish response to Covid was, in many ways, like our approach to most crises – a peculiar blend of chaotic effectiveness. We muddled through with a mixture of good humour, government support, and the stoic recognition that things could always be worse. It's an approach that has served us surprisingly well through centuries of famine, colonisation, and economic collapse.

What the technocratic language of pandemic preparedness misses is the human dimension – the lonely deaths in nursing homes, the cancelled weddings, the graduations reduced to laptop ceremonies, and the funerals attended via live stream. These experiences have traumatised Irish society in ways we're still struggling to articulate.

As we wait for the next wave, whatever form it takes, one wonders if we've learned the deeper lessons of the pandemic: that bureaucratic structures, however well-intentioned, are no substitute for community resilience; that experts, however qualified, cannot predict chaotic systems with certainty; that the most vulnerable among us require protection not just in crisis but always.

Ireland's pandemic experience was, like most Irish experiences, contradictory and complex. We endured Europe's most extended lockdown with remarkable compliance while simultaneously developing elaborate systems to bend the rules just enough to maintain sanity. We trusted authority figures with a level of deference that would make our revolutionary ancestors blush while privately maintaining a healthy contempt often divided along political allegiances.

The next pandemic, when it comes – and come it surely will – will find us better prepared in some ways and woefully unprepared in others. We'll have more consultants, better surveillance systems, and undoubtedly several additional layers of bureaucracy. Whether we'll have addressed the underlying vulnerabilities of our society remains an open question.

In the meantime, the Irish public will do what it has always done - hope for the best, prepare for the worst, and maintain a healthy supply of toilet paper... just in case.