'To boldly go where no-one has gone before'

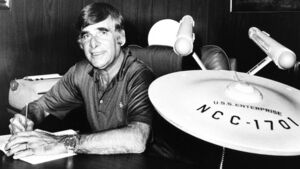

As we move into 2026, I think of Gene Roddenberry and his vision of a better future.

For a television series that began in the 1960s, has had an uncanny habit of staying ahead of its time. Not just technologically, but morally. It imagined a future that wasn’t perfect, but was purposeful - one in which humanity hadn’t solved every problem, yet had at least (eventually) agreed to try.

I grew up with partly by accident, partly by mother’s decree. My Mam wouldn’t let us watch - I never quite understood why - so became our childhood science-fiction universe. The original series - switched off when it became “too scary” (as in an episode where the crew lost their faces, which has stayed with me since) - and later series, which I loved. Its calm confidence rooted in our humanity, its faith in reason and its embrace of the future as a joyful but purposeful exploration of the universe, left a lasting impression on me.

What fascinated me most was not the technology, but the intent behind it. In Season 1, the episode 'The High Ground', during a discussion about political violence and liberation movements, Captain Jean Luc Picard made a pointed historical comparison, noting that Ireland achieved reunification in 2024 - a small but gratifying detail for a nationalist teenager.

In a forerunner to Chat-GPT, the crew interact with an AI computer which operates the starship USS Enterprise and used hands-free “combadges” to communicate with each other. Federation officers used “tricorders” - portable, hand-held scanning and analysis devices used especially in medical and scientific contexts. Captain Picard may be seen using an iPad-like device, 20 years before its invention. All this technology wasn’t prediction so much as aspiration. creator Gene Roddenberry was less interested in guessing what the future would look like, than in asking how it should be.

That distinction matters now more than ever, because the future is no longer a distant horizon. It is arriving quickly, unevenly and without asking our permission. Artificial intelligence is no longer theoretical. This revolutionary leap forward in technology is already shaping how we work, how we learn and how we communicate. As is evidenced in America right now, jobs that did not exist two years ago now do and others, which have been around for generations, don’t. Entire sectors are reorganising themselves around tools that didn’t exist when the decade began.

Despite the doomsayers, I am not afraid of AI. I have worked with it. I see its potential. But like every transformative technology - from electricity to the atomic bomb - it cannot be put back into the bottle. The question is not whether we embrace it, but how. And crucially, whether we allow ourselves to subcontract human responsibility and accountability to robots, machines and software code. AI should assist judgment, not replace it.

If we get this right, Ireland is unusually well placed to benefit. We sit at the cutting edge of technology, not by accident but because of decades of investment, education and exposure to leading US firms. For a small country, our advantage has never been size - it has been intellect (and taxes!). We should lean into that. We should be an innovation economy, confident in research, discovery and imagination, unafraid to occupy niches where we can genuinely excel. A small country can still think boldly, deftly.

But the future is not built only in code. It is built in streets, towns and landscapes. The health of our communities will drive AI innovation, or not.

Ireland needs to have a serious conversation about how we build. We cannot continue sprawling outwards into car-dependent satellite settlements that drain social life and isolate people from one another. High-density, well-designed urban living is not a threat to Irish life; it is a precondition for it in the decades ahead. Cities and towns need to be walkable, liveable and humane. America is learning this the hard way. Build up our lived-in landscape sensibly, sustainably and imaginatively.

And we need to build for the Irish climate we actually have - and the one we are getting. It rains here. It always has. Yet we persist in designing towns that offer no shelter from wind or downpours, as if acknowledging weather were a concession rather than a design principle. Covered walkways and streets, sheltered public spaces and imaginative outdoor environments are not luxuries. They are common sense. Even in Mayo, the ill-fated Connacht GAA Air Dome - destroyed by wind, but ambitious in intent - showed what imagination looks like. The lesson is not to abandon ambition, but to place it wisely and learn from our mistakes. Build better.

We also need to rethink how we tax and value our town centres. Physical shops and public-facing businesses do more than sell goods; they create social space. Yet we burden them with commercial rates while online commerce often escapes equivalent responsibility. We are taxing presence and rewarding absence - and wondering why streets feel empty.

Underlying all of this is a deeper democratic problem. Ireland is one of the most centralised countries in Europe. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, we sit near the bottom when it comes to local autonomy - below countries such as Russia and just above Hungary. Toothless local government, run by unelected administrators, should trouble us deeply.

Real democracy is not just voting every few years. It is allowing communities to decide whether they want hedges or walls along roads, free parking on Saturdays, a roofed pedestrian street, or buildings painted pink if that’s what they collectively choose. It also means allowing communities to make mistakes - because that is how learning happens. Accountable power exercised locally breeds imagination. Dublin-centred power hoarding breeds resentment, conspiracy and enfeebles democracy.

None of this is radical. In many ways, it is deeply traditional. Rural Ireland once understood reuse, repair and sustainability not as ideology but as necessity. The 'meitheal' - collective, voluntary and shared labour - was not a policy; it was a way of life. Informal social rules governed behaviour long before formal regulation arrived. In trying to build a future, we would do well to remember what we were once good at in rural Ireland.

That sense of continuity matters too when we talk about immigration. Immigration is not, in itself, a bad thing. But it must be managed with honesty and care. Placing large numbers of people into small rural communities without consultation or capacity helps no one. Irish history carries a deep memory of imposed settlement - from plantations to empire - and pretending that legacy does not exist is naïve.

Integration works best when it is mutual and respectful. Anyone coming to live in Ireland has a responsibility to understand the culture they are entering, just as my wife and I did when moving to Los Angeles. Respecting diversity does not require erasing the existing culture of a country. We can be inclusive without being self-effacing. Integration, not segregation, is the goal - and that requires confidence as well as kindness.

As a historian, I am struck by how often certainty ages badly. Many people who once spoke with absolute confidence about the future are now footnotes, if remembered at all. Predicting is a mug’s game. Faith, not hope, endures. What lasts longer than ideology is character. Kindness. Patience. The ability to distinguish malice from incompetence, conspiracy from mistake. To aim to do good. Fail. Try. Fail Better. Try again. Succeed.

The world is going through something. Climate change is real. Huge regional demographic changes are real. Wars in Ukraine, Gaza, Sudan, Yemen and elsewhere are real. Sometimes progress requires dealing with people, governments and systems we do not like, because effectiveness matters more than moral posturing. Without a healthy planet, debates on injustice or equality become academic, unless we prioritise the problem.

So as we move into 2026, I think of Gene Roddenberry and his vision of a better future. Not wishing for perfection, nor having simplistic hope, but to act with courage in facing into uncertainty, for behaving thoughtfully and with intent, for empowering imagination and kindness to collectively build a better future for our communities, for Ireland, for the United States, for the world.

To do that, we must boldly go where no one has gone before... and have some craic along the way.

Athbhliain faoi mhaise daoibh go léir.