New pope is the right man for a turbulent era

Pope Leo XIV needs to perform a balancing act in the years ahead.

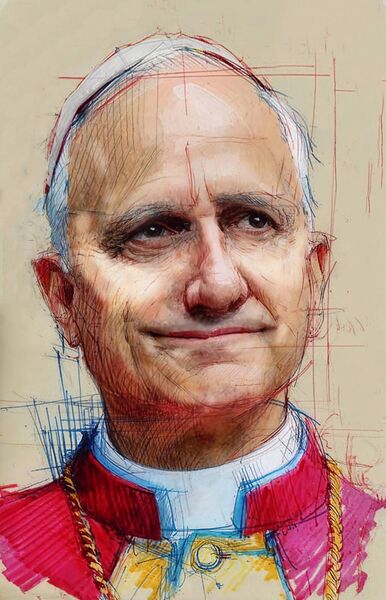

There's something intrinsically Jesuitical about Cardinal Robert Prevost's ascension to the papacy. The Chicago-born, Peruvian-shaped intellectual who now styles himself Leo XIV arrived in Rome like some theological commando, swooping in from the intellectual hinterlands to capture the most gilded throne in Christendom.

The cardinals, those red-hatted princes of the Church, have elected not just another learned cleric but a man who embodies the Church's most fascinating contradiction - its ability to stand with one sensibly shod foot in the 13th century while stretching the other into the quantum realm.

I found myself enthralled as the white smoke billowed. The crowd - that peculiar mix of devout grandmothers clutching rosaries, selfie-stick tourists, and earnest seminarians - erupted with a roar that bounced between Bernini's colonnades like a theological tennis match. 'Habemus Papam!' they cried, though what they actually have is far more interesting than they might realise.

The new Pope, with his mathematician's precision and theologian's curiosity, represents something the secular world persistently fails to understand about Catholicism: its intellectual bloodline runs deeper than the Tiber. The world's media, with its religiously illiterate lens, presents Leo's scientific background as though he'd arrived with a pocket calculator rather than a pectoral cross.

"Pope has a degree in mathematics," they trumpet as if announcing a dog walking on its hind legs.

It's almost willful ignorance. The Catholic Church has been nurturing intellectuals since before Oxford had its first dreaming spire. This institution preserved Aristotle while barbarians were using philosophy books as kindling. It's the enterprise that kept the flame of Western knowledge flickering through Europe's darkest intellectual winter. Our Irish monks weren't just illuminating manuscripts; they were illuminating minds.

Leo XIV, with his thesis on monastic leadership models and his penchant for teaching mathematics in Peruvian slums, isn't the exception to Catholic tradition - he's its embodiment. The Church that condemned Galileo is the same Church that now operates an astronomical observatory where Jesuit brothers track near-Earth objects and contemplate the cosmic origins of our universe. The Church that once feared the printing press now debates artificial intelligence ethics with IBM executives.

In an age when secular universities increasingly resemble expensive finishing schools for the professionally offended, the Catholic intellectual tradition maintains a rigorous commitment to reason that would make Aquinas proud. While academic departments collapse into ideological chaos, Vatican conferences still invite atheist scientists to speak alongside cardinal-theologians, creating a dialogue that spans not just disciplines but metaphysical divides.

This intellectual promiscuity wasn't invented yesterday. When you walk through the Vatican Museums, past the Raphael Rooms, towards the Sistine Chapel, you're traversing a physical timeline of Catholic patronage of arts and sciences. Popes weren't commissioning these works merely to show off their wealth (though let's be honest, there was plenty of that); they were demonstrating the Church's conviction that truth, beauty, and goodness are intertwined pursuits.

Leo XIV comes from the Augustinian order - the same religious family that gave us Gregor Mendel, the friar who meticulously crossbred pea plants in his monastery garden and inadvertently founded the science of genetics. This isn't coincidental. The Augustinians, like their Dominican and Jesuit cousins, have always understood that faith without reason is mere superstition, while reason without faith is an orphaned child searching for its parent.

This comfortable relationship with intellectual inquiry explains how Leo XIV can simultaneously defend traditional moral teachings while acknowledging the looming societal challenges posed by artificial intelligence (AI). For Leo, as for the Church he now leads, there is no contradiction because all truth, whether discovered through revelation or scientific inquiry, has the same divine source.

What makes this Catholic approach to knowledge particularly fascinating is its patience. While our Twitter-addled culture demands immediate answers to complex questions, Catholicism has always played the long game. It took the Church 359 years to formally apologise to Galileo – not because it's particularly slow-witted, but because it thinks in centuries rather than news cycles.

Leo XIV embodies this temporal perspective. During his two decades in Peru, he taught maths to children who lived in cardboard shacks while quietly building educational infrastructure that will outlast him by generations. He did this without press releases or TED Talks - just the patient, persistent work of someone who believes in both salvation and education.

The Church's dual ability to simultaneously preserve ancient wisdom while exploring the cosmos represents Catholicism at its most authentic and provides a sharp rebuke to religious fundamentalists who fear scientific inquiry and secular progressives who dismiss theological insight. The Catholic intellectual tradition suggests that wisdom requires both microscopes and prayer books.

There's a notable passage in Chesterton where he describes the Church as a chariot "thundering through the ages, the dull heresies sprawling and prostrate, the wild truth reeling but erect". Chesterton's image captures something essential about Catholicism's intellectual journey - its willingness to entertain radical ideas while maintaining core convictions, to explore the frontiers of knowledge without abandoning its foundations.

Leo XIV, with his mathematician's mind and missionary's heart, now guides this ancient chariot through particularly treacherous terrain. A world of algorithmic extremism, climate catastrophe, and bioethical quandaries demands a response that is both morally grounded and intellectually nimble. The new Pope seems peculiarly suited to this moment - neither a rigid traditionalist nor a theological dilettante, but something far more interesting: a Catholic intellectual in the grand tradition.

This moment marks more than a papal handover. It's Catholicism doing what it's always done - navigating the space between ancient doctrine and fresh thinking, between timeless truth and current affairs. While today's culture wars pit backwards-looking traditionalists against history-erasing progressives, the Church's middle road offers something rarer: engagement grounded in memory yet unafraid of tomorrow.

Leo brings something special to this balancing act. His scientific mind, comfortable with quantum ambiguities, equips him perfectly for these contradictions. The Church must be certain of what it believes but humble about what it knows, an intellectual disposition that allows Catholics to build particle accelerators while reciting prayers that are fifteen centuries old.

This is Catholicism at its most compelling - not as a museum of antiquated beliefs or a spiritual shopping mall, but as an intellectual tradition that insists on both/and rather than either/or. Both faith and reason. Both tradition and innovation. Both certainty and doubt. The Church under Leo XIV will neither eliminate nor simplify these tensions, but live within them. And that's precisely what our confused modern world lacks: comfort with contradiction.

Watching him bless the masses gathered in St Peter's Square, his choice of papal name struck me as deliberate. Leo - an echo of predecessors who faced their own revolutionary eras with similar intellectual dexterity. Leo XIII, after all, authored , the encyclical that addressed industrial capitalism and laid the groundwork for Catholic social teaching. Leo XIV now inherits the task of addressing algorithmic capitalism and artificial intelligence with the same theological sophistication.

The white smoke has cleared, but the intellectual legacy it announces remains vibrantly present. In a world that increasingly prefers simple answers to complex questions, Pope Leo XIV and the Catholic intellectual tradition he represents offer something far more valuable: the courage to live inside a paradox.