Mid-year musings on our civilisation's decline

Gold - that ancient store of value which civilisations have coveted since before anyone invented fiat currency - sits like the last functioning server in a data centre meltdown. Picture: David Gray/AFP via Getty Images

A wet June has arrived with all the unwelcome punctuality of a tax demand, and with it the dawning realisation that 2025 might be remembered as the year when the West's collective chickens finally decided to come home to roost. The air crackles with the sort of nervous energy you feel in a restaurant kitchen just before the health inspector arrives - everyone knows something unpleasant is about to be discovered, but nobody wants to be the one to lift the lid on what's been festering underneath.

The Americans have managed to elect a man who approaches geopolitics like a hedge fund manager on cocaine, whilst simultaneously discovering that their dollar - that mighty green god around which the world has genuflected for decades - might be suffering from something rather more serious than a mid-life crisis. The BRICS nations are openly discussing alternatives to dollar dominance, with measures to reduce reliance on the US dollar very much on the table, though Brazil has stepped back from advancing a common BRICS currency this year.

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, we Europeans continue our own stately dance toward irrelevance, choreographed by Brussels bureaucrats who've confused spreadsheets with strategy and regulation with results. Germany, that stolid engine of continental prosperity, has become the world's fourth-largest military spender at $88.5 billion in 2024 - a 28% increase, whilst grappling with a budget gap of €16 billion for 2025. Plans are now underway for a €500 billion fund to upgrade Germany's infrastructure and drag the country out of two straight years of recession.

We've spent the better part of three decades constructing a world where money flows faster than Twitter outrage, where supply chains stretch around the globe like fiber optic cables, and where the word 'sovereignty' has become as quaint as using a landline. Now, as the mechanisms of this brave new world begin to seize up like an overheated gaming console, we're rediscovering nationalism with all the enthusiasm of millennials discovering vinyl records.

Consider the spectacle of the West's commercial districts - those glass and steel monuments to quarterly earnings calls. In the USA, office buildings stand approximately 20% empty, with San Francisco hitting a record-high 29% vacancy rate. Moody's economists predict commercial property vacancies could peak at 24% in 2026, whilst average sale prices in the Bay Area have fallen nearly 50% from their 2021 peak to $254 per square foot. The irony is that we spent decades perfecting the art of remote communication, then seemed genuinely surprised when people discovered they could work remotely. Progress - apparently - comes with its own built-in obsolescence.

The Americans have discovered something that previous empires learned the hard way: that being the world's policeman is exhausting work. The dollar's decline isn't just economic; it's existential. When your currency stops being everyone else's problem, you cease being everyone else's solution. Trump has repeatedly threatened 100% tariffs on any BRICS nations that try to replace the US dollar, but threats cannot restore what confidence has eroded.

China, meanwhile, approaches the future with methodical precision, whilst the West argues about the rules of engagement. Their universities churn out engineers whilst ours produce graduates in grievance studies. The chess analogy writes itself: one player contemplating seven moves ahead whilst the other debates whether the pieces are arranged fairly.

The property crisis deserves special mention, if only for its sheer scope. In the US, rising vacancies will probably erode the value of commercial property by as much as $250 billion by 2026. Empty towers stretching toward heaven, shopping centres echoing with the ghostly whispers of commerce past, developments standing vacant as monuments to speculation. It suggests a certain cosmic justice that an economy built on the premise that property always goes up has discovered gravity.

But perhaps the most exquisite irony of our current predicament is how we've managed to create scarcity in the midst of infinite scroll. We have more information than any civilisation in history, yet seem collectively less informed than a Facebook comments section. We have communication technologies that would have seemed magical to previous generations, yet our political discourse has devolved to the level of a pub argument after last orders. We've democratised publishing, only to discover that not everyone has something worth saying.

The European response to these challenges has been characteristically elegant in its futility. More committees, more frameworks, more consultations a bureaucratic equivalent of enterprise software that requires 17 different passwords, and still doesn't work properly. The EU's approach to crisis management suggests an organisation that has confused busy work with actual work, activity with achievement.

Our European leaders promise prosperity whilst presiding over an incremental decline, unity whilst overseeing fragmentation, peace whilst stockpiling weapons. Military spending increased in all world regions in 2024, with Europe seeing a 17% rise to $693 billion. Performance art of the highest order, if performance art could destabilise continents.

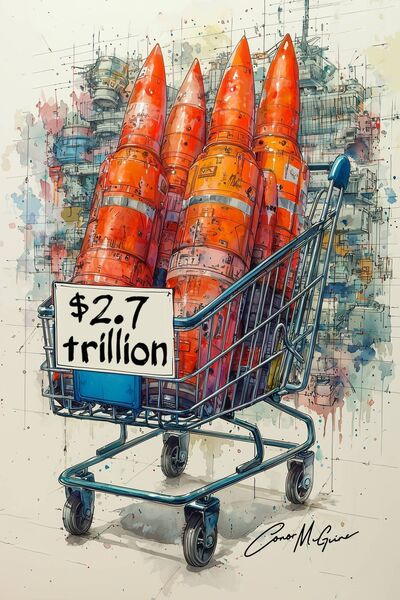

The military-industrial complex feeds on our fears with voracity. Every crisis justifies more spending, every threat demands more weapons, every enemy requires more enemies to fight them. Global military expenditure reached $2,718 billion in 2024, a 9.4% increase - the steepest year-on-year rise since at least the end of the Cold War.

Meanwhile, gold - that ancient store of value which civilisations have coveted since before anyone invented fiat currency - sits like the last functioning server in a data centre meltdown. Goldman Sachs Research predicts gold will rise to $3,700 an ounce by the end of 2025, whilst analysts in a Reuters poll forecast an average annual gold price above $3,000 for the first time. When paper promises start to look increasingly like paper promises, metal begins to look rather sensible.

The technology sector, having promised to democratise everything from information to revolution, discovers that perhaps not all revolutions are improvements. Social media, which was supposed to bring us together, has managed to divide us more efficiently than any demagogue in history.

Artificial intelligence, which was supposed to make us smarter, seems primarily skilled at making us worry about whether we're about to be replaced by something that learned everything it knows from the internet.

As we navigate the second half of 2025, we find ourselves in the curious position of passengers on a ship where the captain insists we're making excellent time whilst the crew quietly distributes life jackets. The destination remains unclear, the weather forecast keeps changing, and the GPS appears to be pointing toward a location that exists only in the marketing brochures.

Yet there's a delusional comfort in watching our decline with style. If civilisation is going to crash, at least it's doing so with the theatrical panache of a well-produced disaster movie. The Romans had their bread and circuses; we have our smartphones and streaming services. The Soviets had their five-year plans and their certainties; we have our anxieties and our artisanal everything.

Perhaps that's what future historians will note about our particular moment: that we faced the end of the world as we knew it with infinite analysis and insufficient action, endless commentary and inadequate solutions. We live-tweeted our decline with the thoroughness of content creators documenting every meal, all whilst missing the bigger picture for the perfectly curated details.

The question, as we scroll toward whatever comes next, isn't whether we can avoid the crash - that ship has not only sailed but seems to have hit an iceberg whilst the crew was busy posting Instagram stories. The question is whether we can manage our decline with sufficient grace to leave something worth salvaging for whoever inherits the mess. On current evidence, the jury is still buffering, but the courtroom appears to have lost its WiFi connection indefinitely.