Francis' papacy was full of contradictions

Pope Francis had imperial tendencies that were most starkly revealed in his crusade against the Latin Mass.

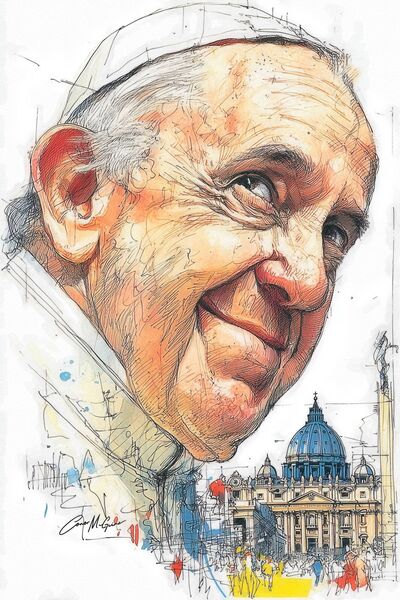

The moment Jorge Mario Bergoglio stepped onto that balcony overlooking St Peter's Square in 2013, a thousand headlines were born. Here was the first Latin American pope, the first Jesuit pope, the first to choose the name Francis. A man who would purportedly drag the Catholic Church into a brave new world by dint of charm, humility and calculated ambiguity. Now, as the world digests the news of his passing at 88, we must consider what kind of Catholic Church he leaves behind.

I've never quite trusted those who claim to be mediators. True peacemakers are inevitably torn apart by the very forces they attempt to reconcile. Like Saint Rodrigo of Córdoba - martyred on the very feast day Francis ascended to the papacy - our late pontiff discovered that standing between warring factions often means becoming their common target.

In the first year of his pontificate, on his visit to Rio De Janeiro, Francis urged young Catholics "to shake up the Church and make a mess". Whether by intent or by the law of unintended consequences, he delivered a mess. For nearly twelve years, this notably humble Argentine conducted a papacy of calculated contradictions that left both progressives and traditionalists feeling simultaneously hopeful and betrayed. He weaponised ambiguity with the precision of a Jesuit tactician, deploying it not as intellectual laziness but as strategic armament.

Consider his famous "Who am I to judge?" – five words that launched a thousand think pieces. The secular press received it as a revolutionary embrace of homosexuality. Conservative Catholics insisted it was nothing of the sort when viewed in the proper context. Francis himself never bothered to clarify, seemingly content to watch the faithful tear each other apart over interpretations.

The man himself was a bundle of contradictions. While portrayed as a humble champion of the common man - the pope who rode in a Fiat and wore sensible shoes - his artistic sensibilities ran toward Germanic complexity: mystic poets, and complex philosophy. Hardly the man-of-the-people image that was carefully crafted for him.

His public persona was equally puzzling. This gentle pastor could be remarkably crude in his rhetoric. While secular journalists swooned over his environmental encyclicals and immigration advocacy, they conveniently ignored his references to "coprophilia" in the media, his complaints about the "air of faggotry in the Vatican," and his penchant for calling his enemies "pickled pepper-faced Christians". The Catholic Dalai Lama he was not.

Francis's admirers would have us remember his championing of the poor, his environmental advocacy in Laudato Si and his outreach to the margins. His critics would point to his authoritarian governance style, his scorched-earth campaign against the Latin Mass, and his bewildering handling of sexual abuse cases. Both portraits contain elements of truth, yet neither captures the essence of this mercurial man.

Perhaps most revealing was his relationship with the media. No previous pope granted so many interviews or spoke so freely to journalists, especially on those notorious airplane press conferences where caution was jettisoned along with cabin pressure. More than 70 of these conversations were substantial enough to be published as books. Through these exchanges, Francis accomplished what doctrinal documents never could: he shifted the Church's conversation without changing a single letter of its laws.

When doctrine proved inconvenient, Francis retreated to footnotes and vague phrasings. His approach to divorced and remarried Catholics receiving communion - buried in a footnote in exemplified this method. He would push boundaries through informal comments, then allow subordinates to clean up the theological mess while he moved on to his next provocative statement.

For a man allegedly committed to 'synodality' and listening, Francis wielded papal authority with remarkable vigour. He issued 75 documents - unilateral papal declarations requiring no consultation. By comparison, his predecessor Benedict XVI issued merely 13 in eight years, while John Paul II produced only 31 across nearly three decades. So much for decentralisation.

Nothing revealed his imperial tendencies more clearly than his crusade against the traditional Latin Mass. What began as requiring priests to seek their bishops' permission escalated to requiring bishops themselves to seek Rome's approval, which was rarely granted. Traditional parishes that had been growing and producing vocations were decimated with the enthusiasm of Henry VIII dissolving monasteries.

On abuse, Francis proved disappointing across the ideological spectrum. While continuing his predecessor's work addressing historical cases, he fumbled new ones spectacularly. The handling of his fellow Jesuit Marko Rupnik, who absolved a woman in confession of having sex with him, was particularly galling. Despite allegations from dozens of women, Rupnik remained a priest, merely shuffled to a different diocese.

Yet we must acknowledge that Francis inherited a Church already divided. The fault lines had been cracking for decades before his pontificate. What made Francis unique was his willingness - perhaps even eagerness - to widen those cracks rather than paper over them. If he wanted to shake things up and make a mess, as he declared in 2013, in this ambition, at least, he succeeded magnificently.

His pontificate leaves the Church polarised between competing visions of Catholicism that seem increasingly incompatible. German bishops flirt with schism, American Catholics split along increasingly partisan lines, traditionalists feel persecuted, progressives feel teased with reforms that never fully materialise. The middle ground - those ordinary Catholics who simply want to attend Mass and live their faith without ideological warfare - feel like besieged inhabitants as they continue to defend the ramparts.

It would be foolish to underestimate Francis's shrewdness because of the obvious turmoil. Pope Francis understood that formal doctrine matters less than pastoral emphasis and controlling the media narrative. When artfully shifting the conversation from sexual ethics to environmental concerns and economic justice, he effectively changed the Church's public face without the messy business of changing its catechism.

His most enduring legacy may be his transformation of the papacy itself. Future popes will be expected to maintain his level of accessibility, to speak extemporaneously rather than through carefully crafted statements. The genie of papal spontaneity cannot be returned to the bottle. Whether this development benefits the Church remains an open question.

Francis's papacy resembled nothing so much as a Wagnerian opera - complex, divisive, occasionally sublime, and frequently exhausting. Like those German compositions he so admired, his pontificate was marked by sudden crescendos, perplexing leitmotifs, and an ending that leaves the audience unsure whether they've witnessed triumph or tragedy.

In death, as in life, Francis defies easy categorisation. Was he a reformer or reactionary? Revolutionary or restorationist? The answer, maddeningly, is both and neither. The Church he leaves behind is neither more progressive nor more traditional, but certainly more fractured and self-conscious.

Saint Rodrigo, whose feast day witnessed Francis's election, when caught between warring brothers, was martyred for refusing to deny his faith. Caught between competing Catholic factions, Pope Francis chose a different path - not martyrdom but strategic ambiguity. Whether history judges this choice as wisdom or weakness will depend largely on what follows in the conclave ahead.

In the coming days, the College of Cardinals will gather to select his successor. Will they choose continuity or correction? Francis appointed the majority of current cardinals, suggesting his influence will extend beyond the grave. Yet the pendulum of Church history has a way of swinging back, sometimes violently.

Whatever comes next, the Catholic Church - that ancient, stubborn institution that has outlasted empires and ideologies - will continue. It survived the contradictions of Francis just as it survived the scandals of the Borgias and the corruption of the Renaissance popes. The truly interesting question is not whether the Church will endure, but which version of it will emerge from the studied mess Francis so enthusiastically created.