Contemplating the great void of retirement

In the end, retirement is less about age and more about assets, less about years and more about yields. Picture: iStock

From my perch in Castlebar, contemplating the ravaged trees and fences of our home's perimeter post an epic storm, I am considering that most bourgeois of life's transitions: retirement. The Romans, with their tedious efficiency, gave us the word 'retire,' though I suspect they had something more terminal in mind.

The contemporary Irish sexagenarian finds himself in an existential pickle that would have Beckett reaching for his notebook. Behind him lies the debacle of the Celtic Tiger years when retirement meant a golf membership and enough spare change to keep the grandchildren in perpetual luxury. Ahead stretches what can only be described as the great void, though marketing types have rebranded it as "the third age" - as if life were a theatrical production with suspiciously optimistic reviews.

The statistics, like an unwanted wedding invite, demand attention: a mere 44% of retirees report genuine happiness in their golden years. The rest find themselves trapped in what I'm calling "The Cultural Centre Syndrome" - endless days punctuated by amateur poetry readings and watercolour classes taught by someone who once saw a Monet in a book.

Retirement takes on a peculiar character out here in the West, where the Atlantic performs its endless demolition job on the coastline with all the subtlety of a Dublin property developer. The local farmers don't retire so much as gradually ossify into their landscape, becoming as much a part of the terrain as the dry stone walls and inexplicable holy wells.

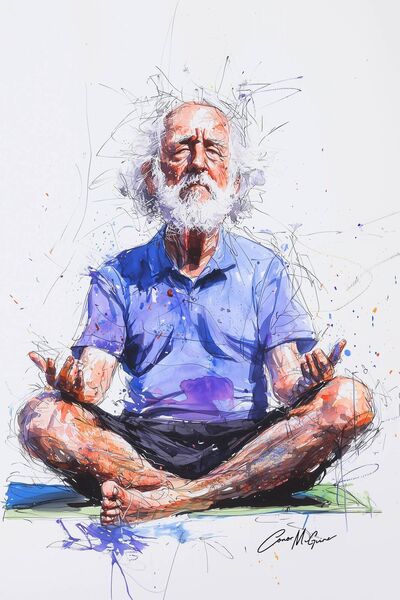

Their sons and daughters, meanwhile, having returned from their Dublin enclaves with tech money and Buddhist meditation apps, are busy turning every abandoned cottage into a mindfulness retreat. It's enough to make you nostalgic for the simple dignity of the Emergency.

Yet perhaps there's something to be said for this new approach to retirement, treating it not as an ending but as what the wellness industry would undoubtedly market as a "personal renaissance journey" (€2,999 per weekend, green smoothies included). Consider the growing tribe of what I'm calling the "post-career creatives" - former accountants making artisanal cheese with milk from heritage goats, ex-bankers writing terrible poetry about their spiritual awakening in the Mayo hills.

The modern retirement landscape has evolved into something that would bewilder our ancestors, who had the good sense to work until they dropped. Now, we have "reverse mentoring" where retirees trade decades of professional wisdom for lessons on how to make their Instagram stories more engaging.

In the West of Ireland, where past and present mingle like whiskey and water in a pub glass, retirement has taken on its own rhythm. Our family histories tell us of women who never truly retired, who instead transformed their roles as circumstances demanded. Though I suspect they weren't running chakra-alignment workshops out of converted cow sheds.

President Michael D. Higgins, our poet-philosopher-in-chief, speaks eloquently about citizenship and engagement in modern Europe. Here in the West, retirement isn't about disengagement but rather about finding new ways to belong - whether it's joining the local historical society (where every meeting inevitably devolves into an argument about who actually started the Civil War) or becoming an ossified political pundit

The traditional markers of retirement success have shifted seismically. It's no longer about the size of your pension pot or the prestige of your former title. Instead, it's about the quality of your Instagram grid, the number of artisanal skills you've mastered, and how many times you can mention yoga and mindfulness in a single conversation without irony.

Some retirees are finding their second wind in pursuits that would make their ancestors spin in their graves - crafting "authentic" Irish experiences for American tourists or finally writing that novel about their grandmother's secret relationship with a travelling tea merchant.

As for our sixty-plus gentleman contemplating this leap into the void, I'd remind him of what every Irish writer worth their salt knows - that endings are just beginnings with better publicity. Retirement isn't about stepping off the stage; it's about choosing which performance piece you want to workshop next.

From my modest desk in Mayo, I've been contemplating the curious geography of retirement. Like a well-aged whiskey, the experience varies dramatically depending on where you're doing the ageing.

We Europeans, masters of the welfare state, have turned retirement into something approaching an art form. In countries where the social safety net is less a net and more a memory foam mattress, retirees are more likely to live alone - not out of isolation, but from choice. It's incredible what a generous pension can do for one's desire for independence.

The Americans, bless their optimistic souls, are experiencing what researchers delicately call a "growing longevity gap" compared to their European counterparts. The near-elderly Americans are showing real declines in health compared to their European peers, who are presumably too busy enjoying their six weeks of vacation to develop lifestyle diseases.

Social exclusion hits differently across European regions, though I suspect being socially excluded in Stockholm feels somewhat different from being socially excluded in Sicily. The quality of life for those over 50 varies dramatically, influenced by those pesky social determinants of health that public health officials are always banging on about.

Meanwhile, in what we euphemistically call the developing world, retirement remains a concept as foreign as a Finnish sauna in the Sahara. While we in the West debate the optimal age for accessing our pension funds, roughly two-thirds of the world's population wake up each morning to the reality that work isn't a choice but a daily necessity until the body simply says "enough".

Some nations are adapting better than others to the challenge of population ageing, though "adapting" in this context often means "frantically trying to figure out how to pay for it all". It's rather like watching different orchestras attempt the same complex piece - some nail it, some muddle through, and some produce something that sounds suspiciously like panic.

From this perspective, I can't help but think we've created a world where retirement has become yet another marker of global inequality. The Scandinavians treat it as a well-earned third act, complete with state-subsidised hobbies and cultural activities. Americans approach it with the same mixture of optimism and anxiety they bring to everything else, while much of the world's population regards it as a concept as remote as a penthouse on Mars.

Even within Europe, the experience fragments like light through a prism. The Mediterranean model of multi-generational family support creates one kind of retirement, while the Nordic emphasis on individual independence crafts another. Then there's the Eastern European approach, which often involves combining traditional family structures with post-communist economic realities - a bit like trying to play chess and checkers simultaneously.

In the end, retirement is less about age and more about assets, less about years and more about yields. While we in the first world debate the optimal balance between golf and grandchildren, most of the world's population continues working until they can't, then rely on family networks that we in the West are busy dismantling in our rush toward individualistic prosperity.

And here in Mayo, where every stone has a story, there's always room for one more tale. Just make sure it's told from a comfortable chair, preferably within easy reach of a decent whiskey, and with the wisdom to know that the best stories often come from those who've lived long enough to distinguish between genuine tradition and tourist board invention.

After all, retirement in the West of Ireland isn't about watching the tide go out - it's about deciding which pretentious metaphor about tides and time you want to bore your grandchildren with. Preferably over a cup of hand-roasted, ethically sourced coffee that costs more than your first car.