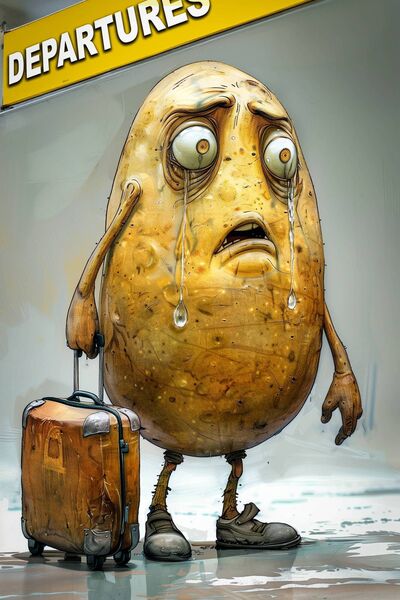

The humble spud has suffered a spectacular fall from grace

The potato's protein level, while low, is of such excellent quality that the World Health Organisation uses it as a standard for assessing other foods.

Not so long ago, a dinner plate in Ireland was considered incomplete without a generous helping of potatoes. A savoury dish, stewed, boiled, baked, or grilled, was inevitably accompanied by a mound of chopped or mashed spuds. The question was never posed: Do you like potatoes? Or, the even more rarified, how do you like your potatoes?

How culinary habits have changed. The humble potato, once lauded as the people's saviour, finds itself in an unusual situation today. From Ireland's fields to its dinner tables, this tuberous crop is going through an unexpected identity crisis. Gone are the days when potatoes reigned supreme as the stomach filler of choice. Today, potatoes are more likely to sit in the frozen food section, becoming another vehicle for salt and fat.

Our humble potato has fallen from grace. Once praised for its life-sustaining powers, this former mainstay has become the poster child for everything objectionable with modern diets. It's a twist that would have left our Irish forebears speechless with shock.

The irony is evident. Millions of people relied on potatoes for nutrition for centuries. In Ireland, it helped to sustain and build a nation, fuelling a population growth that saw our island's population peak at over eight million by the mid-nineteenth century. However, as every student of history knows, our love affair with the potato ended tragically. The Great Famine of 1845-1852 exposed the hazards of agricultural monoculture and colonial neglect, leaving a mark on our communal psyches that still exist today.

Such a disaster might signal the end of the potato's reign. But, like a vigorous weed, it persisted and expanded its impact worldwide. From the Russian steppes to America's heartland, the potato found new homes and admirers.

Fast forward to today, and the potato's reputation has suffered greatly. No longer the darling of nutritionists, it has been reduced to the role of "empty carbs," the most feared of dietary bogeymen. The promotion of low-carb diets and the demonisation of the glycaemic index have dethroned the once-mighty potato, replacing it with trendier, more acceptable alternatives.

In our zeal to denigrate the potato, we have forgotten its peerless nutritional qualities, courting dietary amnesia that is borderline ludicrous. Here's a vegetable with a vitamin C content comparable to oranges, more potassium than a banana, and a fair dosage of vitamin B6 and iron. It is a veritable multivitamin disguised as a lowly potato.

The potato's protein level, while low, is of such excellent quality that the World Health Organisation uses it as a standard for assessing other foods. A potato-based diet supplemented with only milk or butter may support human life indefinitely, which few other single foods can claim. Its ability to supply nutrition with minimum supplementation is nothing short of astounding.

Nonetheless, we've abandoned this nutritional powerhouse and replaced it with exotic grains and pricey leafy greens, duped by cunning marketing and nutritional scare tactics. It's as if we've collectively discarded generations of wisdom, preferring to follow the current dietary trend, no matter how questionable its claims or transitory its advantages.

We Irish, once inextricably linked to the potato by history and necessity, have not been immune to the worldwide mentality shift. The country that once subsisted solely on potatoes now watches as consumption progressively drops, matching global trends with an almost obsessive devotion. In our eagerness to rid ourselves of the final vestiges of our traumatised history, we have thrown out the good with the bad.

The country that once cherished the potato as a life-giver now dismisses it with the same casual disregard as any other western country. This culinary trend reflects Ireland's evolving self-image and desire to be perceived as culinarily sophisticated. However, something uniquely Irish is lost in this rush to accept the new. Once a symbol of thrift and tenacity, the potato is another victim of globalisation's relentless homogenisation.

The contemptuous nickname 'potato eaters', first flung at the Irish by their English conquerors, has evolved into a new sort of gastronomic elitism. Whereas it was previously a term born of colonial contempt, it is now the implicit judgement of the culinary elite. This contempt for the lowly spud stinks of classism, a culinary caste system in which the ordinary, unmodified potato is permanently demoted to the bottom rung.

It's a unique case of cultural amnesia, and we've forgotten that this tuber once supported entire civilisations. Ironically, many of these culinary snobs are most likely descended from the 'potato eaters' they now tacitly disdain. Their rejection of potatoes is motivated by desire rather than taste, a desperate attempt to remove oneself from a diet they regard as subsistence food. They foster dietary colonialism by allowing western food trends to govern global palates and discarding traditional mainstays to favour whichever grain or green is now in vogue.

Consumption has dropped in the United States, home of supersised fries and all-you-can-eat potato skins. The average American consumes 30% less potatoes than during the vegetable's peak. A few decades ago, this kind of deterioration would have been inconceivable. The inconvenience of fresh potatoes, in particular, has been replaced by processed, frozen alternatives. It's as if we've all agreed that the only acceptable type of potato has been deep-fried, salted, and sealed in plastic.

This transformation is more than just an issue of changing preferences. It mirrors broader societal shifts, like the decline of home-cooked meals, the normalisation of convenience foods, and the frenetic pace of modern life. Who has time to peel and cook potatoes when a bag of frozen chips is only a minute away?

The potato's fall from favour reveals more about our society than it does about the vegetable. Our rejection of this once-standard dish underscores our present fixation with convenience and our inclination to baulk at the monotony of food preparation. We are a society constantly looking for the easy option, even when it comes to something as basic as what we consume.

Our current situation may provide an ironic twist. As we face the challenges of feeding a growing global population while addressing climate change, we may return to the potato. Its ability to generate large yields in tiny spaces, tolerance to different climates, and nutritional value make it a crop worth consideration.

But if the potato is to retake its role in modern diets and agricultural systems, it must overcome its reputation as a nutritional villain and peasant staple. This will necessitate a shift in perspective and a willingness to look beyond fad diets and simplistic dietary philosophies. The potato must be reassessed as a diverse, healthy food that may be included in a well-balanced diet rather than a source of "empty carbs".

The potato's evolution from an Andean mainstay to a worldwide crop to a nutritional pariah is a story that encompasses centuries of human history. It is a tale of colonialism and globalisation, scientific advancement and dietary fads, feast and famine. As we face the challenges of climate change and food poverty, the simple potato may play a role in moulding our future. I am a proud potato grower and consumer with a low carbon footprint. Please serve me a new season spud, fresh from the garden, boiled in water, and served with a dab of butter and salt before proffering any continental culinary interpretation.

The potato's fate will ultimately be defined by our choices rather than by its unrivalled qualities. Will we continue to dismiss it as a second-class food, or will we acknowledge its virtue as a sustainable, healthy crop? The answer could have far-reaching consequences for our national and global food security.