The hardest thing is doing nothing at all

There’s one thing no one tells you about being a parent. The job description changes continually, usually without warning.

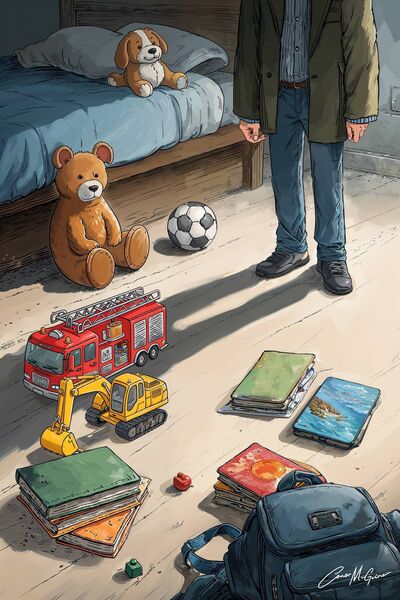

There's a particular quality to silence you only learn when your offspring leaves home. It’s not the absence of noise but the unfamiliar silence that invades when the parenting purpose has been removed. It settles in your chest when you realise the daily architecture of fatherhood, all those years of scaffolding and shoring up, has been quietly dismantled overnight. Your child or children are in college now, and you're sitting there, in a house that's eerily quiet, trying to animate your day enough so it might make some familiar noise.

I've been busily painting the same stretch of the Mayo coastline for years, capturing the same rocks, the ambient light, and ever-changing weather. The thing about landscape painting is that it teaches you about letting go of the moment. You can't force the tumultuous Atlantic to behave; you can't still the billowing clouds and ever-shifting tides. An artist has to work with what's there moment to moment, and I'm beginning to think fatherhood might be the same, only it's taken me eighteen years plus to see it.

The impulse, when your son heads off to college, is to pack him full of wisdom, to distil everything you've learned into a rucksack - all the face-plants and false starts, the small victories and large humiliations - into some sort of portable survival kit. As if personal wisdom could be vacuum-packed like smoked salmon. But I gave up, realising I was packing for my past life, not his.

There’s one thing no one tells you about being a parent. The job description changes continually, usually without warning. When they're small, well, you're a god. Everything you say is gospel, every scraped knee requires your intervention, every bedtime monster demands your particular brand of monster-slaying. You get rather fond of being adored and inflated by such innocent esteem, and then adolescence arrives like a house guest who's forgotten to leave, and suddenly you're not quite trending, if not an occasional anachronism. That's fair enough, as I can vividly recall my own adolescent intolerance of elders.

But the next bit is something else entirely as you're meant to step back now, not away, mind you, but back. Give them room to make precisely the mistakes you spent their entire childhood trying to prevent, and it goes against every protective instinct. Evolution has spent millions of years fine-tuning parents to keep their offspring alive, and now you're supposed to override the programming and watch them walk into traffic. Metaphorical traffic, mostly, but sometimes actual traffic if they've had a few drinks with the lads, might be a tad rowdy and can't remember which way the cars are coming.

I do find myself reaching for the phone, wanting to check in, make sure he's eating something other than toast, that he's going to lectures, that he hasn't accidentally joined a cult or taken up with someone wholly unsuitable. Then I stop. Because what I'm really doing is reassuring myself that I'm still relevant. That the job isn't done. That I'm not redundant.

The truth is considerably less comfortable. He doesn't need me the way he used to. Doesn't need me to explain how the world works, where to find his shoes, or why that girl in his peer group probably isn't the love of his life. He needs me to shut up and trust him and believe that somewhere in the years of nurture, between the knee scrapes and the homework tears and the continual battles around screen time, something took hold. That he's actually capable of working it out himself.

This is where parenthood stops being about what you do and starts being about what you don't do and the interventions you decide not to deliver. The advice you don't dispense, the rescue missions you don't launch, and it's harder than anything that came before, this deliberate absence. At least when they're small, you can measure your success in tangible ways. Did they eat their vegetables, did they say please, or did they make it to school on time with all their school books? Now you're measuring it in negative space, in all the phone calls you resisted making and the opinions you keep buttoned.

I frequently think about my own father, trying to remember if he went through this change sensibly, seven times in total. I suspect he did, though he certainly wouldn't have called it that, as his generation didn't do emotional archaeology or obvious vulnerability. You just got on with things and kept the softer emotions private, the doubts locked away where they couldn't frighten the children or, perhaps, yourself. Today, we grown men are allowed to be indulgently sentimental. We can admit that watching your son drive away with a carload of belongings feels like someone's stabbed a vital organ you forgot was pulsating under your ribcage.

Thank God I can see the winter beauty in County Mayo, as there's something about living on the edge of the windswept Atlantic that makes absence feel all the more acute. The western landscape is all about what's not there - the trees on the shoreline stripped bare of leaves, the generations of relatives and friends who left for Boston and never came back. You feel it in the stones. All that beautiful emptiness teaching you about space and distance, about how things can be far away and still somehow present.

My son and I don't talk every day; sometimes nearly a week goes by before we talk. When we do talk, it's about nothing in particular. I try not to excavate but prefer he surrender his thoughts - his essay deadlines, my latest article for the , whether the Leaving Cert is still as traumatising as when he sat it the year before.

It’s all light, surface stuff, not too challenging for a faceless phone conversation, but underneath, I'm listening for something else, the encouraging signs that he's finding his footing, that he's learning to stand in that space between a dizzying array of stimuli and a measured, adult response. It’s that unnerving place where you get to choose who you're going to be in society. We, the mere parental elders, call it growing up, a gross simplification of a tumultuous reality.

The ever-present temptation is to reach in and smooth things over when they go wrong. And they will go wrong, often spectacularly and repeatedly, in ways you can't possibly anticipate. He'll get his heart broken again, or he'll fail at something that will disrupt his whole schedule, and he'll discover that being clever isn't the same as being wise, and that kindness takes more courage than cleverness ever will. Part of me wants to spare him all of that, but the more sensible part knows you can't and shouldn’t.

You can’t be afraid of letting go, as you're not actually letting go of them; you're letting go of your idea of them, the mistaken version you've been carrying around in your head, the one where you know exactly who they are and what they need. That version was always fiction anyway, just better edited and curated than most. The real person, now an adult, the one currently negotiating a busy social life and seminars, that person has always been there, just waiting for permission to blossom without your continual intervention and tacit approval.

So I continue to paint and write my articles, and my son hasn't left, not really; he's just moved into the next room, and I'm learning it's wise to knock before entering.

The silence isn't as tangible as it was a few months ago, and on most mornings, I even appreciate it, as the house now organises itself around my schedule rather than the school timetable. I can work late without feeling guilty, and can spend as long as I fancy watching the light change over Nephin without anyone asking what's for dinner.

But late at night or in the winter dusk, when the house settles into its own rhythms, I sometimes walk past his room, and I pause there, just for a moment, remembering all the versions of him that grew up in that space. The needy infant, the joy-filled toddler and the suddenly private and assertive teenager.

But parenthood doesn't end, it just changes shape and becomes quieter, more about faith than action. You step back and hope that all those years of showing up, of being boringly consistent, of trying to model something approaching decency - you hope it somehow sank in and took root. So when he's standing at some crossroads trying to decide which way to turn, something you said or did or demonstrated without meaning to might whisper in his ear.

Or maybe it won't, and maybe he'll work it out entirely on his own, through trial and error and the odd spectacular failure. Either way, he'll be fine, better than fine, and he'll be himself, which is all any of us can hope to be.

And I'll still be here, painting the same shifting light on Nephin's hills, while struggling with the wording of some article. I am learning what my father probably knew all along: the hardest thing about being a parent is trusting that you've done enough, even when it feels like you've done nothing at all.