Scammers didn't just arrive with the Internet

There's something strangely reassuring about scams. Not the losing-your-life-savings part, but the timeless persistence of deceit. As we worry about artificial intelligence (AI) stealing jobs and a climate catastrophe, con artists keep refining their oldest trick: exploiting human credulity and greed for profit. Methods and technology change, but our gullibility remains constant. Human nature hasn’t evolved, even as the con has gone digital.

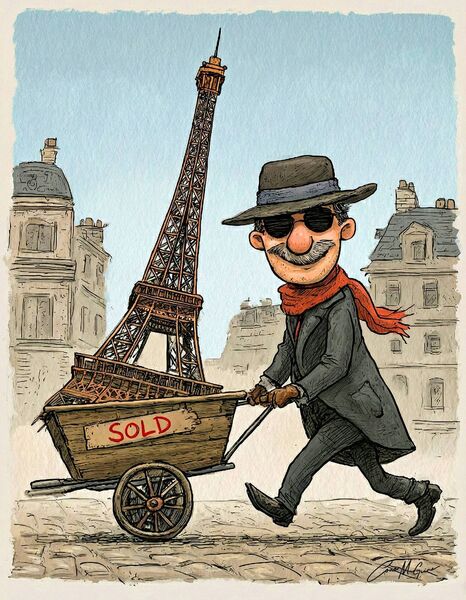

History provides some choice examples. An enterprising Victor Lustig managed to sell the Eiffel Tower twice. In the 1920s, this magnificently audacious charlatan convinced scrap metal dealers that France was flogging off its most famous landmark because maintenance was becoming too expensive. He artfully created fake government documents, held secret meetings, promptly pocketed the cash, and simply vanished. Then, and this is the beautiful part, he did it again, the same tower but a different victim. You'd think the word would get around. But that's the thing about scams, isn't it? They work because we want them to work. Our desire for the con to be real overrides our skepticism: we want the beautiful woman on Facebook to actually fancy us, the investment opportunity to be real, the Nigerian prince to exist.

What marks the digital age is the industrial scale of fraud, not new motives. Last month, reporters uncovered Shunda Park in Myanmar, a fraud factory employing over 3,500 workers, many of them trafficked, all participating in digital cons. Despite widespread civil unrest, this busy hub continues the online evolution of classic grifts, old swindles executed with new efficiency.

The tour revealed open-plan offices filled with monitors, and walls displayed motivational slogans like 'Keep going', 'Dream chaser' and 'Making money matters the most'. Video call suites featured staged business books and trending modern art, convincing enough for targeted victims. There were photos of false identities, even makeshift punishment rooms, and heaps of discarded phones with SIM cards littering the floor.

Who ran this fraud operation? A Chinese crime network. The workers spent twelve-hour shifts in what one survivor called a repeated cycle: sleep, eat, scam. Some workers' tasks were repetitive and strictly measured, and they faced unending abuse if they didn’t meet their overseers' targets. It's a blend of exploitative working conditions that seems almost unreal but is entirely real.

What stands out about Shunda Park - beyond the abuse and forced labour - is its professional organisation. This wasn't a small operation. They had manuals, playbooks, and detailed scripts. Notebooks showed the effort put into creating realistic fake personas, such as Chen Minchen, whose fictional life was detailed. The amount of information rivals the background work of writers.

The scam manuals themselves read like something from a particularly sinister marketing course. Target women in China over 30, but in Taiwan, make it 40 and even older. Days one to three, get to know the basics, then days three to five, follow through by making up childhood stories to become more relatable. Days five to seven introduce romance, especially in the evening when women are supposedly more receptive. Tell her you admire her for internal beauty, not outward appearance.

Then follows the kicker, politely demand respect for your professional judgment before introducing the enticing investment scheme. Strike precisely, the manual instructs, and create her dreams. One notebook ended with a directive that could've been written by the devil himself: "Induce the customer to add more money until all her savings and loans are completely wiped out."

This industrial approach to fraud extracted at least ten billion dollars from the United States in 2024. Globally, reported cryptocurrency scams reached $14 billion in 2025. The average scam payment rose from $782 to $2,764 in a single year, and scams are now highly organised and efficient at taking money from vulnerable victims.

Today, the scam artist has at his fingertips the boundless benefits of AI, reenabled with deepfakes, cloned voices, and algorithm-crafted messages, enabling new scams indistinguishable from reality. Traditional warning signs fade, and AI-backed scams have become more persuasive and immensely lucrative, but they exploit the same old human vulnerabilities as technology intensifies the con, and the core swindle endures.

The psychology of it all hasn't changed, though. Scammers still exploit the same basic human weaknesses they always have: our loneliness, greed, fear, and ever-present vanity. They create urgency, enticing the victim to pay now or lose the lucrative opportunity. They impersonate figures of authority - we're the police, a concerned tax office, and your reliable local bank - and they offer social proof and data showing happy investors. They isolate you - don't tell anyone about this incredible opportunity. And they build emotional connections, because nothing makes you quite as stupid as affection, or the promise of it.

The internet has simply made it easier to find vulnerable people at scale. Three-quarters of American adults have experienced at least one online scam, and Ireland may not be far behind. The majority of cases go unreported as most victims don't tell anyone, usually out of a mixture of embarrassment and shame, or sheer exhaustion at admitting they fell for an obvious scam, momentarily blinded by greed.

What is perhaps most striking is how little we victims have adapted, even as the scams have evolved and become ever more sophisticated. From playing cards and street hustles to AI-powered deceits, our age-old susceptibility to what seems too good to be true endures despite our informed vigilance. Radically clever technology may have entered and changed the landscape, but the marks with their behaviours, desires, and vulnerabilities remain largely unchanged. The digital makeover may be frighteningly efficient, but the frail human element remains a constant.

There is a certain dark comedy in all of this, as even right now, as you read, workers in Southeast Asia are being abused for not sending enough 'hellos' on Facebook. In Kansas, a truck driver falls for someone who doesn't exist but answers his romantic longings. Meanwhile, in Ireland, a poor pensioner invests in a company that exists only as an impermanent website, promising dividends his pension could never deliver. The scale and consequences would be almost humorous if they weren’t so individually grim and ruinous.

The real question isn’t whether scams will persist because they will, as long as there’s gullibility and opportunity. The issue is what happens when reality itself becomes uncertain, and every digital interaction is suspect. At that point, the con is not just a crime; it’s a crisis of trust, proving the resilience and danger of this ancient profession in digital form.

Until then, scams will continue. Sleep, eat, scam, eat, sleep, scam. This process repeats. Some may even view it as a tradition difficult to stop. I just want to turn off every device, unsubscribe from every digital account and squirrel my meagre savings under the nearest mattress.