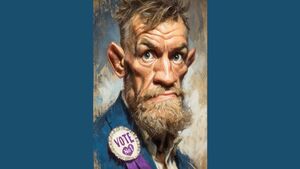

Lord of the Dance squares up to the Notorious

As Conor McGregor (above) and Michael Flatley show their interest in becoming the next president, that the other known candidates actually have qualifications for the job seems almost an aside. Picture: Conor McKeown

If you'd told me ten years ago that Ireland's next presidential contest might pit a man whose feet were insured for $57 million against another who was recently the subject of a civil rape case, I'd have assumed you'd been at the poitín. Yet here we are, watching Michael Flatley – he of the thunderous tap and the windmilling arms – prepare to lock horns with Conor McGregor for the privilege of shaking hands with visiting dignitaries and cutting ribbons at county fairs. It's democracy by way of Beckett: two men, trapped in their own magnificent theatrics, performing Irishness for an audience that can't quite believe what it's seeing.

What does it tell us that two leading contenders for the Park are a dancer who made Celtic mysticism into a Vegas act and a fighter who turned Dublin mouth into a global brand? Nothing good about our capacity for self-reflection, I'd venture. Flatley took step-dancing – something you might have done at a Féis or céilí – and turned it into a billion-dollar pantomime complete with wind machines and leather trousers. McGregor dragged cage fighting out of grotty warehouses and made it respectable enough for your mother to watch on pay-per-view. Both men are brilliant at what they do, which is selling Ireland back to itself at a hefty markup. They've got that particularly Irish gift for being simultaneously cocksure and neurotic, the same restless energy that gave us Joyce and Bono and every other export who's ever made the world pay attention to this damp rock in the Atlantic.

Both men understand the power of performance in ways that traditional politicians often struggle to grasp. Flatley's revelation of his presidential ambitions during a High Court case over renovation disputes at his County Cork mansion is itself a masterclass in timing and theatre. The "material change in circumstances" that brought this to light – his planned return from Monaco to seek nominations – reads like a plot device from one of his own productions. McGregor's declaration at the White House, complete with what appears to have been Donald Trump's tacit endorsement, demonstrates his instinctive understanding of the modern media landscape.

Strip away the circus act and you're left with a genuine question: what exactly do we want from the person who lives in the Park? The presidency might be ceremonial, but it's not meaningless – ask any country that's ever had to watch their head of state embarrass them on the international stage. Higgins gave us fourteen years of thoughtful speeches and careful dignity, a president who could quote Yeats at state dinners and actually mean it. Whoever follows him won't just be cutting ribbons and hosting garden parties; they'll be the face we show the world at precisely the moment when nobody can agree what that face should look like. Are we the land of saints and scholars, or the country that gave you Riverdance and UFC champions? Both, probably, which is precisely the problem.

Flatley's critique that Irish people lack "a true proper deep voice that speaks their language" is intriguing, not least because it comes from a man who spent decades creating precisely such a voice through dance and music. His assertion that the "average person on the street" is unhappy with the status quo taps into a genuine undercurrent of dissatisfaction with political establishments across the Western world. Whether a 67-year-old dancer can credibly claim to represent the concerns of ordinary citizens is, of course, another matter entirely.

McGregor's appeal operates on different frequencies altogether. His civil case difficulties aside, he represents a particular kind of modern Irish success story – the working-class Dublin boy who conquered the world through sheer force of personality and an absolute refusal to accept limitations. McGregor's whole shtick – the preening, the feuds, the carefully orchestrated outrages – speaks to young people who've given up on politicians altogether. Why listen to some TD drone on about housing policy when you can watch a man in a three-piece suit promise to knock seven shades out of his opponent? It's politics as professional wrestling and it works because, at least, it's honest about being a performance.

But here's the rub: getting on the ballot isn't like getting a fight card. You need twenty TDs or four councils to back you, which means grovelling to the very establishment figures your whole brand is built on despising. Independent Ireland's lukewarm offer to "talk" to potential candidates – provided they can prove they're not completely delusional – is political speak for "show us the money". Both Flatley and McGregor will have to prostrate themselves before backbench nobodies and county councillors, begging for nominations like buskers working for coins. It's the sort of humiliation that would break lesser egos, but then again, these are men who've built careers on the principle that any attention is good attention.

Flatley's dash from Monaco smacks of a need for personal reinvention – a man who's exhausted his other options and fancies one last bow before the curtain falls. His recent attempt at cinema, the poorly received , suggests someone still hunting for applause in increasingly unlikely places. The presidency isn't Riverdance with a state car; it's months of tedious ceremonies and diplomatic small talk. Try to imagine Flatley at the Ballina Agricultural Show, nodding sagely at a prize bull while some farmer explains the finer points of livestock breeding. The nimble-footed dancer who raised entire arenas on their feet, weeping at his artistic genius, reduced to asking whether the rain would hold off for the sheep-shearing competition. It's like watching Nureyev judge a three-legged race.

McGregor faces the reverse dilemma: he's spent years perfecting the art of calculated outrage, and now he wants a job that requires him to bite his tongue for seven years straight. You don't go from calling opponents "rats" and "weasels" to hosting tea parties for visiting dignitaries without serious pharmaceutical intervention. The presidency is performance, certainly, but it's mime – all gesture and no voice. McGregor without his mouth would be like John McCormack with laryngitis: technically still there, but missing the point entirely.

The other candidates must be watching this unfold with the weary resignation of serious actors who've just discovered their Chekhov revival is being upstaged by a busking competition outside. McGuinness has spent years mastering the dark arts of Brussels bureaucracy while Connolly represents that admirable strain of bloody-minded independence that periodically saves Irish politics from complete cynicism. Both women have actual qualifications for the job, which in this context makes them about as exciting as a tax return. Against this backdrop of conventional political achievement, the celebrity candidates risk appearing as mere entertainment, a political equivalent of novelty acts.

Yet dismissing either Flatley or McGregor as frivolous would be a mistake. Both men have demonstrated remarkable entrepreneurial vision and an instinctual ability to connect with audiences on an emotional level that traditional politicians would envy. In an era when authenticity has become the most valuable political currency, their very outsider status might prove to be their greatest asset.

If both men make it onto the ballot, we're in for a campaign that will make our usual political pantomimes look like parish council meetings. Flatley will arrive at debates in a fog of dry ice and Celtic mysticism. At the same time, McGregor will spend his time psychologically dismantling opponents with the sort of verbal savagery that made grown men weep before he'd even thrown a punch. Poor Mairead McGuinness and Catherine Connolly will be left looking like the sensible adults trying to restore order while the children set fire to the classroom. Whether this circus elevates the presidency or turns it into light entertainment depends entirely on whether you think democracy needs more razzmatazz or less.

Perhaps most intriguingly, both candidates represent different aspects of the Irish-American experience that has shaped so much of our cultural identity. Flatley's success in packaging Irish tradition for global consumption mirrors the way Irish-America has long served as a lens through which Ireland views itself. McGregor's brasher, more confrontational approach reflects a newer, more aggressive assertion of Irish identity on the world stage.

The ultimate irony is that in seeking to represent authentic Irish voices, both men embody the performance of Irishness rather than its lived reality. Their campaigns will inevitably become exercises in competing definitions of what it means to be Irish in the modern world. Whether the electorate will choose the choreographed elegance of the dancer or the calculated chaos of the fighter – or reject both in favour of more conventional political experience – remains to be seen.

What seems inevitable is that Irish politics, like Irish culture, has always thrived on its capacity to surprise, entertain, and confound in equal measure. In Flatley versus McGregor, we may have found the perfect embodiment of that tradition.