Christmas is a time to enjoy the best of our human qualities

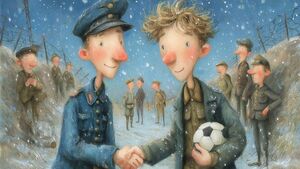

The Christmas truce of 1914 happened because soldiers on both sides desperately needed to remember they were human. Illustration: Conor McGuire

There's a carol that manages to stop wars. Not metaphorically - actually stop them. Bullets in mid-air, bayonets lowered, the whole ghastly machinery of human cruelty paused like a film reel jammed in the projector. It happened in 1914, in the frozen mud of No Man's Land, when German soldiers started singing and British troops, recognising the tune through the darkness, joined in with .

Think about that for a moment. These men had spent months trying to kill each other with industrialised efficiency, and a lullaby - a simple, three-verse lullaby written by an Austrian priest a century earlier - made them remember they were human. They climbed out of their trenches, shook hands, played football, and showed each other photographs of their families. The song didn't end the war, of course. Wars aren't that easy. But for a few hours, it made the whole murderous enterprise seem suddenly ridiculous.

I think about this every Christmas when some tedious contrarian starts banging on about how the holiday has become too commercial, too indulgent, too secular, too much of everything except whatever hair-shirt version of piety they're peddling. Because reminds us of something we keep forgetting: the whole point of Christmas - the entire reason for its existence - is to stop. To pause. To remember that we're not machines, not consumers, not productive units or tax brackets or data points. We're people. Fragile, ridiculous, glorious people who need beauty and rest and each other.

The song itself is almost beautifully simple - a mother, a baby and some peace and quiet. There is no attempt at theological complexity, no grand metaphysical claims, just the smallest, most intimate moment imaginable. A woman and her newborn child in the hush of night. It's been translated into 140 languages, not because it's profound but because it's universal. Every culture understands exhaustion. Every culture knows what it means to long for silence after chaos, for tenderness after cruelty, for sleep after the long day's work.

And here's the thing about Christmas that drives the scolds and the Puritans absolutely spare: it's about pleasure. Guilty, unearned, excessive pleasure. Eating too much. Drinking too much. Singing badly. Staying up late. Giving gifts we can't quite afford to people who don't really need them. It's gloriously, defiantly wasteful. The whole season is one long middle finger to productivity culture, to optimisation, to the grim calculus of utility that governs the rest of our year.

The philosophers - at least the interesting ones - have always understood this. David Hume, that wonderful old Scottish atheist with his wine cellar and his dinner parties, thought the point of being good wasn't to suffer but to be "useful or agreeable" to yourself and others. What a radical idea! That even Christian virtue might actually involve having an occasional nice time.

Christmas, properly celebrated, is Hume's revenge on the Puritans. It's a festival of the senses in a world that wants us to live in our heads, staring at screens, optimising our productivity, monetising our hobbies. The smell of pine. The taste of something too rich, too sweet. The feeling of being slightly drunk in the middle of the afternoon. The sound of people you love laughing too loudly. These aren't shameful indulgences to be regretted come January. They're the whole point.

We've gotten weirdly embarrassed about this. You can see it in how we talk about Christmas now - always with an apologetic shrug, always hedged with anxiety about excess. We eat the mince pie and immediately announce we'll "work it off" in January. We pour the third glass of wine while promising ourselves a Dry January. We buy the expensive gift and then feel guilty about it for weeks, as if pleasure were something to be rationed, doled out sparingly, always followed by penance.

But this is precisely backwards. Pleasure's not some dirty little secret you need to confess to your priest. It's the thing you're supposed to be doing with some of your time here. Emilie du Châtelet wrote that we ought to strew our path with flowers. Flowers, mind you. She could have said "make the best of things" or "find the silver lining" or any of those dreary platitudes we trot out when life's being difficult. But no - flowers. Deliberately chosen, actively scattered, completely unnecessary flowers just because they're lovely. Most of us can barely manage to avoid the brambles.

This isn't hedonism in the debauched sense. It's something subtler and more radical: the idea that human happiness matters. That our brief time here deserves to be filled with moments of genuine joy, not just grinding productivity interrupted by guilty treats. That sometimes the most meaningful thing you can do is light candles, sing songs, eat too much pudding, and tell the people you love that you love them.

understands this at a cellular level. It's not asking you to be better, to work harder, to achieve more. It's asking you to stop. To be quiet. To appreciate the extraordinary miracle of ordinary tenderness. A mother with her child. That's all. That's enough. That's everything.

We've lost something in our anxiety about excess and indulgence: the understanding that these moments of collective joy are actually necessary. Not nice-to-have or guilty pleasures but necessary. We need festivals, times when the normal rules are suspended, when we're allowed - expected, even - to be excessive, generous, silly, drunk, overfed, and delighted. Because the alternative is a world where everything is productive, everything is optimised and even people are justified by their utility.

The Christmas truce of 1914 happened because soldiers on both sides desperately needed to remember they were human. The carol gave them permission. It said: You don't have to be efficient right now. You don't have to be at war. You can just be tired men a long way from home, singing a song your mother probably sang to you once.

We're not in trenches, but we're at war all the same - with our schedules, our ambitions, our endless to-do lists, the relentless pressure to be more, do more, achieve more. Christmas is meant to be a ceasefire. Not forever. Just for a few days. Long enough to remember what we're actually working for.

So sing the carol. All six verses, if you know them. Drink the mulled wine. Eat the thing you usually wouldn't eat. Buy the ridiculous gift. Stay up too late. Sleep in too long. Be unproductive. Be wasteful. Be excessive. Not because you've earned it - God, who came up with that idea? - but because you're human, and being human means sometimes stopping to notice that despite everything, despite all the awfulness and cruelty and grinding difficulty of being alive, there are still moments of absurd, irrational beauty.

A German soldier spontaneously breaks into singing in the darkness while a British soldier recognises the tune and both of them, for just a moment, lay down their weapons to sing together about peace on earth. If that's a moment not worth celebrating, if that small miracle of ordinary decency isn't worth a few days of guilty pleasure, we might ask ourselves what's the point of any of it?

The Puritans made Christmas illegal in 17th-century England, pronouncing the celebration sinful with killjoy glee. Thankfully, they lost that argument, and Christmas survived precisely because people instinctively understood what philosophers have been saying for centuries. Our lives are short, often complicated, and occasionally brutal. We need our festivals, our fleeting indulgences, refreshed spiritually by our silly, excessive, unproductive moments of collective joy.

So this Christmas, do me a favour. When someone starts wittering on about commercialisation or overindulgence or how things aren't what they used to be, just start singing. Sing if you're feeling traditional or if you're proud to be Irish and want to swear a bit. Doesn't matter. Just make noise. Make joy. Make trouble if necessary.

Because that's what the carol teaches us, in the end. Sometimes the most radical thing you can do is stop fighting, stop working, stop being sensible, productive, and appropriate. Sometimes you just need to sing something beautiful together and remember - however briefly, however imperfectly - that we're all in this mess together.

All is calm. All is bright. Even if it's not, even if it's chaos and noise and the usual shambles, we can believe for a few hours that it is. And maybe, just maybe, that believing makes it real enough to matter.