Tales of the Banshee

Brendan Gleeson and Colin Farrell in The Banshees of Insherin. Picture: Courtesy of Searchlight Pictures

With an abundance of Irish films and actors nominated in the 95th Academy Awards earlier this year, it is no wonder the ceremony was dubbed ‘The Green Oscars’. Nominated in nine categories, writer and director Martin McDonagh’s darkly comedic tale of friendship and loss, , was one of the most critically-acclaimed movies to ever emerge from Ireland.

If international audiences were not already familiar with word ‘banshee’- an everyday utterance in the Irish vernacular - they certainly will be, thanks to the global success of the visually stunning melodrama filmed on location in Achill and Inis Meain.

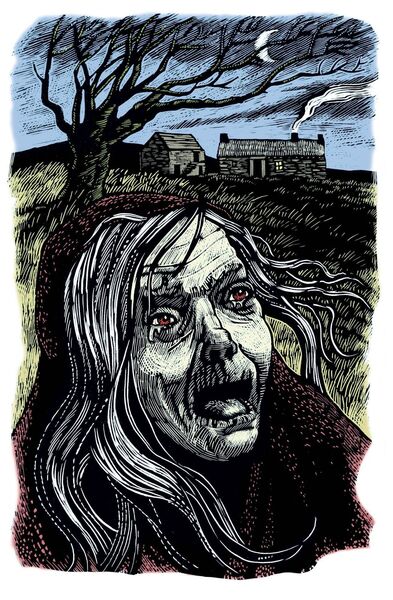

Taken from the Gaelic ‘Bean Sídhe’ or ‘Bean Sí’, banshee translates as ‘ faerie woman’. A malevolent being from the otherworld, she is said to be a foreteller of death - those who hear her mournful cries will soon grieve the loss of a family member. Stories of Bean Sí have long been rooted in Irish folklore and mythology, and no more so than in the county of Mayo.

Published in 1888, David R. McNally’s recounts an ancient legend of “a noble family whose name is still familiar in Mayo”. According to the tale, the head of the clan deceived and murdered a young woman in his youth. With her dying breath, the woman cursed her aggressor and promised to “attend him and all his descendants forever more”. Many years passed, and the chieftain's youthful crime was all but forgotten. One night he and his family were seated by the fire when suddenly the most horrible shrieks were outside the castle walls.

“All ran out but saw nothing. During the night the screams continued. The unhappy man recognised the cry of the Banshee as the voice of the young girl he murdered. The next night he was assassinated by one of his followers when again the wild unearthly screams were heard."

From that day forward, the vengeful spirit never failed to notify the noble family of an impending death, with her shrieking cries.

This story fits neatly with the thirteenth-century notion of the Banshee being solely associated with families of great Gaelic descent with ‘Mac’ or ‘O’ in their name. As time passed, she became more rooted in the oral tradition and could be heard by any person, no matter their station in society.

A story from eighteenth-century South Mayo was recalled by C.S. Boswell in , published in 1901. A well-respected doctor was sitting at the bedside of a sick man one night. Satisfied that his patient was in no grave danger, the doctor retired to another room to get some rest. It was not long before a young servant girl came knocking furiously on his door, crying: “Och the mashter - the poor mashter!”

“Hold your tongue!'' the irritated doctor replied. “The master is quite well and you would do well not to wake him with your crying."

“Och doctor, don’t you hear the Banshee!” exclaimed the girl, who was evidently scared out of her senses.

“Banshee indeed!” snapped the frustrated medic.

Undeterred, the girl dragged the doctor to the master’s room, where sure enough he was met with “a low, mournful sound borne upon the wind”. The doctor flew to the window and peered out into the night, as if expecting to find some logical explanation, when “from out of the moonlight could be heard a loud plaintive note, rising and sinking, and rising again”. Startled out of his scepticism, the doctor rushed to the bedside of his patient, who he found to be in the last breath of life.

It is said that in some parts of Mayo, the Banshee was called ‘An Bhean Chaointe’ (The Keening Woman). Her role was not to forewarn death, but rather to lament the passing of souls. She could often be seen sitting on a rock at sea, dressed in a cloak of grey, combing her long hair.

In 1851, the reported on the “extermination” of Cloggernagh - a small village between Castlebar and Westport - which had been all but ravaged in the Great Famine. Bemoaning the destruction of the once beautifully scenic and prosperous village, the commented thus: “Well indeed may the Banshee weal over the ruins of Ireland - and more particularly those of Mayo - whose glory is forever fled!”

The National Folklore Commission’s Schools Collection is an invaluable treasure trove of Ireland’s rich oral tradition. Founded in 1935, the Commission was tasked with preserving stories, songs, poems, remedies, piseógs and place names for future generations. Each national school in the 26 counties was invited to contribute to the ambitious project. Schoolchilden were asked to transcribe information from older neighbours and relatives. The result is a unique collection that offers the modern reader a window into the past. It will come as no surprise that various tales of the Banshee feature heavily in the contributions from Mayo schools.

In Caherrobert, Kilmaine, Annie Browne offered a detailed description of the Banshee, and her custom of rapping on the doors of homes she visited.

“She usually has a light in her hand, and is seen coming on the road from the dead person's house, and always crying. She is dressed in white and comes to the house where the person is dead. She makes a great noise and sometimes knocks at the door making a great rattle. When she is heard the people put their backs to the doors till the noise is gone away."

75-year-old Margaret Gardiner of Newtownwhite -a townland between Ballina and Killala - told a young William Jackson of her relatives’s direct encounter with the Banshee.

“My grandfather caught the sheet (i.e. cloak) of the Banshee. Each night she came outside the door crying for it. One night he stood inside the door of the house and asked “Cé tá ag buaidhreadh ort?” (Who is troubling you?) She said she wanted the sheet and could not do without it. He put the sheet on the window with the fork and she left the tracks of her fingers on the fork. Then he told her to go out to the rock in the midst of the sea and she replied “Why don’t you send me to the graveyard where I will have shelter.”

In Killgellia, Attymass, schoolboy Thomas Gaughan learned of the shapeshifting abilities of the Banshee from Bridget O’Hara.

“There is a bird called the Bean Síde that cries when a person dies. He comes to the house in the night and cries around it….if you want to hunt him away from the house you should make the sign of the cross three times.”

James Burke, aged 65, of Ballyholla, The Neale, told a Banshee tale with an unexpected twist to Joan Daly.

“The Banshee would steal everything she could from the village (of Cross). Every night she used to go to the graveyard wailing. The people of the village were very much afraid of her and... would be indoors before twelve o'clock at night.

"One of the men of the village said he would go to the graveyard and see if it was Bean Sidhe, who was stealing the things from the people. When he went to the graveyard, and who was the Bean Sidhe, but one of the women of the village. She was making them afraid by her crying, and was stealing all the things from the people."

Tales of the Banshee have somewhat diminished in recent times. The mere utterance of her name does not appear to strike fear among younger generations, as it once did.

But there are many who firmly believe she has never gone away.

Given that her mystic powers allow her to “follow the old race across distant lands, for space and time, offer no hindrance”, perhaps she might make an appearance of her own at some future Oscars ceremony, now that she has got the Hollywood treatment!