58 metres that separate Mayo from the pinnacle

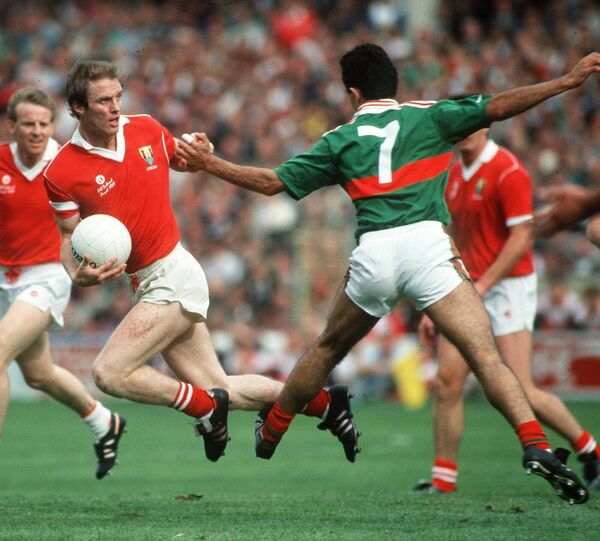

Trevor Mortimer takes off in pursuit of Declan O'Sullivan during the game between Mayo and Kerry in the All-Ireland SFC final of 2006.

Our, Mayo’s, problem isn’t conquering the Everest of the GAA, we did that three times already. No, it’s the inability to transfer the climbing team into a Kerry or Dublin mountaineering outfit, teams who sample that rarified oxygen and plant the flag atop on a regular basis. The figures have us as happy campers all the way to the Death Zone where the last remaining obstacle to the Everest summit remained. It was called the Hillary Step*, a forty foot sheer rock face of ice. Traverse the Hillary Step and a mere 58 metres separated the climber from the biggest achievement, conquering Everest.

The magnitude is in the figures. Climbing 8,790 metres to the Chair and surmounting it, cleared the way to the summit of Everest that stood 8848 metres. 58 freezing snow covered metres to the mountain top separated the winner from the loser. That, in mountaineering terms, has been Mayo’s journey for much of my seven decades here on earth.

This article is a journey, no recourse to notes, facts nor figures. It’s simply a 72-year-old man trying to recall what stood out from each final we reached since 1989.

I first wrote for the Western People in 2001 with an article called The Lost Cause, a kind of attempt at humour around our famine from 1951 as seen by a departed soul in limbo. My next foray was a piece to the then sports editor around 2003 bemoaning the fact that I felt better players were not playing with the county than were. This was the era that McDonald, O’Neill and David Brady weren’t available for the championship. Around 2005, my wife, unbeknownst to me, dumped five pieces I had typed, with wrong font size, paragraphs badly broken, which was my attempt at recording the emotions of Mayo’s finals of 1989, ’96, ’97 and ’04 and putting them onto the Western People’s sports editor’s desk to ask him to put her out of her misery over her husband’s Mayo obsession.

Thinking back on how I constructed those articles in 2005, I assume it would be from an angle different than the one I would take today with an almost 20 year gap of gestation and reflection. The graph from simply happy to have been there in 1989 to almost apathy after the 2021 loss, would have been steep. I’m not sure who said it, a journalist or ex player, but it went along the lines of ‘Mayo’s biggest problem was they never met a side like themselves when it mattered.’ How true. We are an outlier. We are up there with the two brand leaders in final appearances, Kerry and Dublin, but below Galway, Cork, Tyrone and Down in titles. How come Down could win five titles from six finals since 1961, Tyrone four titles since 2003, all on less appearances than us?

Yet we shouldn’t conflate being an outlier with failure. We aren’t failures. Our high flying final day loss is often gleefully seized on by others who have no pedigree at all. Our sense of ‘failure’ is final day ‘failure’. But final day failure is not failure. Failure belongs to the 18 counties, most who haven’t ever reached an All-Ireland final ever. No, failures we are not, just unfortunate to dwell on the crosshairs that intersect between one step from immortality and derision by those never fit to lace our boots. Such are the slings and arrows of losing an All-Ireland final.

One theme you will come across, as mentioned above regarding not meeting teams like ourselves, is that it may possibly be true. Indulge me.

Again going simply on memory and emotion, my trip to the All-Ireland final of 1989. Born one year after we won in 1951, I was 37 that September. So long a gap that a sentence combing Mayo and All-Ireland final merited a second glance. The Ireland of 1989 may in some cases be the Ireland of 1899. September Sunday morning under a grey laden sky, will it rain, maybe it won’t kind of day. Rathmines and Ranelagh still the bedsit homes of the country lad and lass. Shops and cafes not opening until midday. Mass still a guilty niggle if you missed it.

The trip past Mountjoy Jail on the North Circular road is still vivid. Its grey edifice mimicked the grey sky. Turning left onto Lower Drumcondra Road suddenly grey gave way to a sea of green and red. Flags and colour everywhere. The pilgrim had found his church. My heart lifted. Eventually Quinn’s opened. Pints and bluff, dreams and aspirations melded into hope. Looking back today, Cork needed a Mayo to free them from doing a Galway of 1940/41/42, losing three in-a-row finals, narrowly, to Kerry twice and Dublin. Losing wasn’t an option for Cork. They were in Hannibal’s territory, backs to a wall, if a way through couldn’t be found, one then had to created.

Their losses to Meath in 1987 and ’88 were sulphuric, nasty spiteful games. Losing to nice Mayo in 1989 simply wasn’t an option. On retrospection, this was the first indication of one team meeting another that wouldn’t present the issues Meath did the previous two years. Mayo were strictly footballers first; dark arts and win at all costs weren’t in their golf bag as options. And yet I theorise had we won in 1989, our path after would have been different. You see, we did an awful lot right that year but were too honest in our approach. Cork were battle hardened the previous two seasons, we hadn’t operated in that rarefied oxygen. We met our Hillary Step.

Looking back today, September 1989 was truly in another century. Most of the match is a pastiche of blur to me now. I recall leaping with Finnerty’s goal and sinking with his miss but my main recollection is that Cork controlled the last 10 minutes. Naively, I stood around for Dinny Allen’s speech with the cup, a perfunctory acknowledgement of Mayo being worthy opponents blah de blah plus a longer well aimed tirade about men in crows nests who dared doubt the Leesiders. Today we call the crow’s nest occupants analysts and panellists. I saw how winners take all.

The Mayo team flew back to Knock Airport the day after the final. At the time it seemed normal, even cool and forward looking. Mayo people had an airport to fly into. We were somebody. Then I thought…why? Would we have also flown the cup down with us had we won it? Depriving those who migrated from the county and settled in Leinster years earlier, loyal Mayo people who fly their flags to this day. Were we not going to cross the Shannon like Galway crossed at Athlone? Sharing our win with greater Connacht? Just a thought. What 1989 did was awaken us though.

The 1996 final and replay can be condensed into one. Bright sunshine days both matches, sulphur and dynamite. Meath being Meath and Mayo finding their inner Meath. Anyone at those two matches won’t want me to recount them. They are seared into the brain. Our first 20 minutes of total dominance mixed with awful misses allowing Meath, battered onto the ropes, hope for the half-time bell. Six points clear, needing a fresh set of legs in the engine room to close it out, we got reeled in at the death. A bouncing ball of all things sundered us. Many thought the replay would get us found out but it didn’t. Both sides lost a man and many thought us the biggest affected with the sending offs. I didn’t. Coyle brought something into the Meath team that’s undefinable, un-buyable but centric to their makeup.

The All-Ireland finals of 1996 mixed two emotions for me. Sheer pride of being from Mayo and in our team but mixed with anger of blowing the best chance ever to land the damn thing. Many things done correct, retrospective views might have seen certain things done differently. The heartbreak of that defeat made many assume us broken, but we weren’t. We made the following year’s final. Again sunshine but Kerry the opponent. A team we had broken on the semi-final wheel a year earlier. Now they were back. Injuries had scarred us. Cahill, Brady and O’Neill out with bad injuries and carrying injuries in a few positions. A revamped middle two had changed the cavaliers of a year earlier into a more cautious outfit in 1997.

If Mayo’s fine semi-final win over Kerry in ’96 displayed the best of our carefree style, a final was to be fought under different rules of engagement. Kerry were primed from the off, a non-vintage Kerry might I add, but in truth they didn’t need to be brilliant to beat us. We were a pale shadow of the tyros of a year earlier. Again Kerry met the right team. They ended an 11 year famine. Our, by then 46 year famine, continued. No more to be said other than we failed to fire on the day. Injuries and positional movement played a part but they had final day hunger sated. It wouldn’t be the last time the Kingdom would feast on us.

We never went away but we did fly much lower. Between 1998 and 2001 the second worst thing happened to us. The worst is losing a final, the second worst was Galway winning a pair of finals with Mayo man John O’Mahony in charge. Those were hard winters for the Great Plains. What could we say?

Back again in 2004, surprisingly after a tepid 2003, once more facing Kerry. A great win over reigning All-Ireland champions Tyrone in that year’s quarter-final was stress-tested in two awful games against Fermanagh in the semi-final. Kerry saw what Kerry needed to see and September 2004 saw them rain hell and fire down on us. It was awful. It was pitiable. Once more we listened to a Kerry manager speak about a famine. Not intending to but hitting the mark. Their famine? A last final win in 2000. Ours still frozen in 1951. Salt and open wounds, still behind Hillary Step.

As luck would have it, a remarkable semi-final win over an over confident Dublin side in 2006 had us back in that year’s final. Again the rain and fire landed mostly on our full-back line but it wasn’t their fault then, nor back in ’04, just that we failed to staunch the outfield launching pads. In September 2006 we had returned with a similar back line but Kerry had now added to their arsenal full-forward Kieran Donaghy. Inside 10 first-half minutes his 6’5” frame and the entire Kerry team wreaked carnage all around. If 2004 was hell, this went beyond it. We were the wrong team in the wrong place at the wrong time. But. We are a resilient people, we hear the jibes, yes, and get hurt by them, but do what we always do as a Mayo people, get back in the saddle.

If 2010 was another nadir, within a season the green roots of redemption were showing. Yes, beaten by Kerry in the semi-final of 2011, but enough tall trees were emerging to show that maybe we could start thinking about Everest once more. A year later, 2012, we possibly fired our best bullets and displayed our best form against Dublin in that year’s semi-final. Finally we were in a final against a team that weren’t Kerry, Meath or another blue blood.

Donegal hadn’t our pedigree but they possessed their own version of Hannibal, the great general, in Jim McGuinness who had ripped the old GAA rules of engagement to shreds. Ultra defensive with line breakers from deep feeding the twin towers of Murphy and McFadden, we would now see which team would use the other to make the historic breakthrough. Finally we would play our equals.

*An avalanche around 2016 dislodged and changed Hillary Step, that sheer forty foot ice barrier to Everest’s summit. It now has packed snow, still formidable and takes out its share of would be summiteers. The ultimate machine that separates winners from participants.