We no longer see the sacred in the ordinary

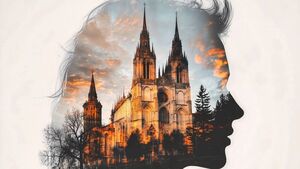

When we consider the numerous 19th-century churches and cathedrals that define the skyline of every Irish town and village, we see a demonstration of the type of institutional permanency that both draws and repels modern skeptics. Illustration: Conor McGuire

The story of Irish Christianity provides a fascinating analogy to Ireland's current situation. Those early Celtic Christians knew something that we've mostly forgotten: Christianity isn't supposed to be a polite social convention, but rather a disruptive, uncontrolled force that reshapes physical and spiritual terrain.

Consider the changing nature of Irish Catholic identity, which demonstrates how faith becomes inextricably linked with cultural identity - for better or worse.

In our modern spiritual marketplace, where faith is often reduced to inspirational quotes on Instagram or the occasional wedding ceremony, we need what Leonard Foley calls 'Believing in Jesus' - not as a historical figure or a philosophical concept but as a living, breathing reality that demands response.

Mirroring my late journey from willful indifference to this weekly tightrope of cultural criticism, a lively faith involves more than mere intellectual acquiescence, it requires a radical reorientation of one's life compass. When we consider the numerous 19th-century churches and cathedrals that define the skyline of every Irish town and village, we see a demonstration of the type of institutional permanency that both draws and repels modern skeptics.

What we're witnessing isn't simply a crisis of faith but a crisis of imagination. Through unchallenged lukewarmness, we become spiritual tourists instead of sturdy pilgrims, seeking ease rather than committing to authentic spirituality's long and often difficult path. The fundamentals of Christianity can be memorised, but they are meaningless without the transformative experience of genuine faith.

This progressive departure from conventional belief represents a clear societal shift away from any type of over-taxing commitment and we have developed a phobia of spiritual certainty, refusing to follow any particular tradition or practice. There is a consequent trend in young people who are rejecting committed relationships in favour of a no-obligation 'situationship'.

The solution is not making faith more palatable to modern tastes but recovering its essential discomfiting. We must rediscover the compelling, sometimes uncomfortable truth that authentic faith demands everything while promising even more.

The quiet exodus continues not because faith has been disproven but because it has been domesticated. We've turned the lion of Judah into a household cat, content to purr in the corner rather than roar through the wilderness of our souls. The challenge isn't to make Christianity more relevant but to help people understand that it is devastatingly, uncomfortably, gloriously relevant.

What's needed isn't a new marketing strategy for an old faith but a rediscovery of its ancient power. The early Irish Christians produced some of Christianity's greatest spiritual treasures, a cultural expression of their understanding that it was greater than an isolated Sunday ritual. Instead, it was an integrated way of life that created a thriving culture and civilisation. They did not participate in endless focus groups or relevance committees; all they needed was the electrifying grace that transformed fishermen into apostles and persecutors into saints.

Perhaps the most tragic aspect of this drift isn't the loss of religious observance but the loss of spiritual imagination. We've forgotten how to see the world as enchanted, recognise the sacred in the ordinary, and find God in the gaps between our certainties. The solution isn't more programmes or better catechesis, though these have their place. The solution is recovering the fundamentals of spiritual awe.

We may have to consider that, paradoxically, the path forward may be backward - not to recreate some imagined golden period of faith, but to rediscover the basic components that made Christianity not only credible but irresistibly attractive. This realisation could move us beyond mere knowledge of church teaching; it necessitates a lived experience of spiritual realities that alters both the believer and the world in which they live.

The solution isn't to make faith easier but to make it more obviously worth the difficulty it has always entailed. Our unexamined materialism is obscuring our spiritual vistas.

Consider the parallel between religious doubt and cultural identity. Just as Celtic Christianity altered physical and spiritual environments, our current trajectory reflects a greater societal malaise. The ancient Irish did not distinguish between holy and profane; their faith permeated everything, from art to agriculture.

Today's spiritual crisis is caused not just by institutional failures and our fragmented attitude to life, but also by categorising spirituality into handy Sunday slots that are disconnected from Monday's reality. This split results in spiritual schizophrenia, in which belief becomes increasingly meaningless in daily life.

The solution entails more than just slavishly attending more services or learning more spiritual doctrine by rote. This approach demands that we radically reintegrate faith into all aspects of life while recovering the sacramental perspective, in which every meal is a festival and every conversation a potential revelation.

We Irish would do well to consider how the early Irish monks viewed their manuscripts: not as just texts to be read, but as things of beauty that combined the divine and human. Their illuminated manuscripts were more than simply books; they were prayers in ink and gold that elevated reading to the level of adoration.

An integration of faith and everyday life challenges us to embrace a fundamental shift in our understanding of reality itself, not merely a reinvigorated religious attendance. In addition to offering unmatched wealth and comfort, the modern world has eliminated the mystique that formerly gave faith legitimacy and significance.

The drift from faith accelerates because we've lost the ability to see the sacred in the ordinary. When everything becomes explainable, nothing remains mysterious. Yet paradoxically, as science reveals more about the universe's complexity, it should inspire greater wonder, not less. The problem isn't that modern people find faith too difficult; it's that they don't perceive it as difficult enough to be worth the effort.

Our spiritual ancestors understood this. They didn't try to make faith convenient; they recognised that its inconvenience was part of its transformative power. The ancient disciplines of prayer and fasting, the companions of every contemplative, practiced by Christians over the millennia, were intended as more than just painful acts of discipline and sacrifice, they were meant to motivate people to grow spiritually and be more selfless.

There is cause for optimism since our culture is seeing an intriguing phenomenon: the spread of cultural Christianity among those who were previously doubtful. The function of Christianity in contemporary society has been the subject of renewed discussion following a string of high-profile conversions in the past few months.

Even Richard Dawkins, formerly Christianity's most outspoken adversary, now calls himself a "cultural Christian," albeit this approach has been criticised for wanting to retain Christianity's benefits while rejecting its fundamental principles.

This development reflects a broader recognition that Christianity continues to have a fundamental influence on many secular moral ideas, particularly during times of personal crisis and a large number of notable philosophers are abandoning their former anti-religious attitudes in favour of a Christian perspective. This transformation pertains to matters beyond conventional faith.

'Cultural Christianity' is a questionable hybrid, a trojan horse, blending modern concerns with a form of religious identity that seeks to integrate historic but uncomfortable Christian principles with modern secular worldviews. It addresses fundamental questions about the nature of faith and its cultural legacy in today's environment. Others describe quitting faith as an intellectual rite of passage, only to learn that their relationship with spirituality, like their body, is constantly evolving.

It is the war of the ages, a clash between worldly standards and Christian precepts. The fundamental distinction between the Christian churches and the secular world is more than just an institutional divide, it signals an insistence of a spiritual reality that cannot be healed through an elegantly portrayed compromise.

This difference is not a fault to be erased or fixed as it is a divine artifice that defines the vast abyss that exists between the sacred and the profane. This permanent tension is not merely spiritual and philosophical, but is Christianity's most fundamental cornerstone, safeguarding the church's prophetic voice through the millennia and transforming its mission in a world that regularly opposes its principles and goals.

We redefine such divine decrees at our peril.