The letter from America was once a big part of Christmas

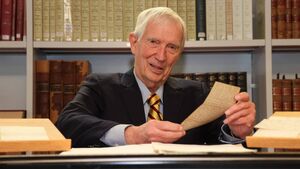

Kerby A. Miller at University of Galway Library to mark the launch of Imirce, a digital repository of thousands of Irish emigrant letters. Picture: Aengus McMahon

As the importance of letters and letter-writing fades from view, in the face of electronic communications, it can be difficult to imagine the anticipation that receiving a letter once held. At a time when countless people left the Ox Mountain region for a better life in America, the letter home was often the only link that existed between separated loved ones.

While such communications were confined to those who could write, these letters contained stories of success and failure, love and heartbreak, births, marriages and deaths. These letters home, often received in time for Christmas, sometimes contained American dollars, an essential lifeline for poor people at home.

The massive numbers of Irish who emigrated to the New World created an almighty tonnage of mail. Letters were the only real form of communication at the time. A hunger for news from home sought by those who were away, coupled with a hunger for financial support needed by those at home, meant that huge volumes of mail travelled both ways. Mayo.ie, in a blog, , gives some idea of the magnitude of letter-writing in the nineteenth century.

The letters mainly discussed family and friends but also provided an insight into the emigrant’s reflections on their new life. Some accounts were exaggerated while others were brutally realistic. Although most of these letters are long gone, some were kept by families and the descendants of those who wrote them.

A project at the University of Galway has recently been set up to preserve a considerable amount of these letters. The project sprang from letters collected by US academic, Kerby Miller. Over 40 years ago, Miller issued an appeal for such letters that he felt may have been kept by loved ones, and he was right. He received thousands of replies containing what amounted to a massive social history.

The countless letters he later transcribed are now preserved in the Imirce Collection, an online searchable archive containing the stories of Irish emigrants going back over the centuries. An RTÉ 1 radio documentary, , explores the new archive and meets the people working on it. In the documentary you can also hear the letters read and the stories they contain; stories of work and life, sadness and longing, travel and adventure.

One letter in the Imirce Collection, with a Sligo connection, highlights the fact that before the Famine, it was mostly the educated and the relatively well-to-do who made the trip to America and subsequently wrote letters home. The letter is described below and while it gives an account of separation, it seems it is a separation that can be easily restored.

Thomas Gunning, New York City, to Major Charles O'Hara, Collooney, County Sligo, 26 August 1831.

At the time of the Famine, and in the years afterwards, the Irish travelled to America in their droves. These people were often not well educated and had little or no means. Letters written at this time often paint pictures of shocking hardship and utter desperation.

In a piece written by Matt Keogh for Irish Central in recent weeks, under the heading, , he mentions a particular letter, also with a Sligo connection, that highlights the plight of the poor at the time. The letter writing is skillful, even if the story is harrowing. The following is an excerpt from the letter from Michael and Mary Rush from Ardnaglass, Co Sligo who are writing to their father, Thomas, in Carillon, Ontario in September 1846.

Henry Gavigan, formerly from the Ox Mountains and then living in New York, refers to the death of his mother and the recent Wall Street Crash in a letter, written to a friend at home in December 1929.

Today, these letters provide us with a window into the past. Some of them were written to send joyful news of the births of a new Irish American generation that would never experience poverty again. Others were written in despair by people who longed for loved ones. This mass emigration, sometimes of whole families, left mothers and fathers at home, bereft. Parents at that time, while poor, were no less loving than the parents of today and saying goodbye forever to their living children was a devastation beyond our imagination.

Think back to the last time you received a hand-written letter from a family member. I would venture to say it was quite a while ago. While we have every imaginable way of communicating with each other today, little of it involves the craft or the skill of letter writing.

As for creating a social history for the future, there simply will not be a lasting record. There will be no story, no written account, no news of success, no lines of regret, no photograph, no tear-stained page. We will never dig a social history out of the rushed emails and poorly spelled text messages of today. We might find it somewhere else, but we will no longer find it in old hand-written letter.