Most 'influencers' are just merchandisers

We cannot pin all the blame on the influencers. They are merely responding rationally to social and economic incentives. The root of the rot lies more deeply in our culture's obsession with wealth, celebrity and perfection.

There is a phenomenon spreading across the internet: the rise of social media influencers is well underway. These self-appointed arbiters of taste and style are busily insinuating into every crevice of culture and commerce, their perfectly filtered faces beaming from our screens like so many artificially whitened teeth. Where once celebrities had to rely on talent and charisma to capture the public's attention, now all it takes is a smartphone camera, a willingness to share every thought, and the brass neck self-promotion skills of a particularly aggressive estate agent.

Instagram, YouTube, and, more recently, TikTok have allowed 'celebrities' to manufacture a sense of intimacy and connection with a legion of followers, fostering the illusion that these airbrushed avatars are cherished friends rather than just another advertising channel. Brands, desperate to seem relevant, have enthusiastically sponsored these faux celebs, hoping their "authenticity" will translate to sales.

Yet what, precisely, are these influencers influencing us to do? Their Insta-glam lifestyles of endless holidays, pseudo-profound musings and pouting poolside selfies seem less an inspiration than a vicarious form of aspiration. The influencers and their followers are mainly female (though not exclusively), and their performative perfection leaves mere mortals feeling flabby, flawed and inadequate. Rather than motivating fans to become better people, they encourage competitive preening, conspicuous consumption and the profound sadness of comparing unfiltered lives to their curated highlight reels.

History has always provided tastemakers and trendsetters, from Oscar Wilde to Andy Warhol and Anna Wintour. But the difference is that those arbiters usually had some tangible claim to authority, whether through artistic talent, sartorial innovation or industry insight. Too many influencers are mere merchandisers, selling not just handbags and teeth whiteners but themselves. They are their own wafer-thin product.

Attention is the prevailing currency in a social media economy defined by likes, follows and swipe-ups. And thus, we have an arms race of outsized personalities, each trying to shout louder for their slice of the market. The yoga bunnies are contorting themselves into human pretzels, the fitness fanatics with more developed glutes than personalities, and the wanderlust nomads are making the rest of us feel inadequate for not perpetually globetrotting. Each has visual grammar and verbal tics, but the message is remarkably uniform: buy what I'm selling, and you too can feel complete.

Culturally, there will always be a need for trendsetters who inspire us to see the world through fresh eyes. The difference is that influencers are salespeople, not trendsetters. They crave money, not respect. Their goal is not to inspire but to advertise. And in the rush to monetise their "personal brands", they have made it virtually impossible to differentiate organic recommendations from paid endorsements. The line between user and used has never been blurrier.

This is simply capitalism's circle of life - clever influencers seizing an opportunity to profit from their ability to sell aspirational lifestyles. Undoubtedly, some offer valuable service journalism, reviewing products or providing tips. But too many feel less like real people than Instagram bots, manically liking and commenting to game algorithms in hopes of being noticed by a sponsor. They are the Avon ladies of the digital era.

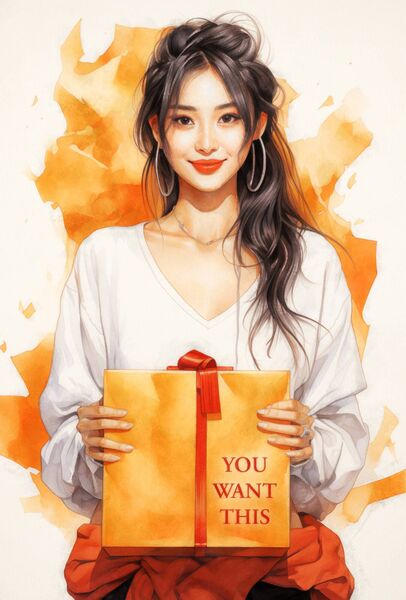

Take the case of Chinese livestreamer Zheng Xiang Xiang, who recently gained a million new followers in just three days. Her meteoric rise to fame was fueled by selling cheap trinkets housed in iconic Hermès boxes. By wrapping mass-produced fakery in luxury packaging, she created an elevated unboxing experience that drove over $18 million in sales in one week.

This ingenious contrast of premium presentation and budget products underscores how savvy influencers leverage packaging and perception - not just the products themselves - to shape desire and drive sales.

When Zheng Xiang Xiang recently gained those million new followers on her Chinese live-streaming channel in just three days, sceptical onlookers wondered if it was too good to be true. But the secret to her success was simple: packaging theatre.

Are there lessons aspiring entrepreneurs and marketers can glean from this viral phenomenon?

The most obvious lesson is the power of authenticity. Xiang Xiang differentiated herself by keeping things simple and low-key, letting the products take centre stage. Her stripped-down, minimally edited videos felt genuine, breeding customer trust and loyalty.

The unboxing theatre was also ingeniously crafted. The Hermès packaging elevated the product's desirability through its immediate visual pop and associations with exclusivity. It was marketing sleight of hand at its finest.

This underscores how presentation matters as much as the products in shaping perception and driving sales. The unboxing experience became an exercise in aspirational branding.

Xiang Xiang also demonstrates the compounding effects of consistency. For over six years, she quietly built her business before 'overnight' fame. Entrepreneurial success depends on daily habits over time, not quick fixes.

Finally, she stayed true to her vision and aesthetic despite industry pressure to be flashier. Her belief in her unique approach paid off handsomely when the world took notice.

Ultimately, Xiang Xiang's genius was recognising unboxing theatre's potential for influencer marketing. She carved her own path by ignoring conventional live-streaming wisdom in favour of an authentic and considered aesthetic, eschewing the temptation of self-aggrandisement.

Her meteoric rise is a case study of how small businesses can generate demand through savvy branding. By elevating the customer experience thoughtfully, Xiang Xiang created outsized value from inexpensive products. Substance won out over smoke and mirrors. Xiang Xiang's story is a reminder that with creativity and commitment, entrepreneurs can find success on their own terms.

The influence bubble will pass in time when seemingly unassailable social media giants have crumbled. The quest for "relevance" may be as fleeting as last season's It bag. There are already signs of influencer fatigue setting in amongst consumers. But for now, these preening wannabes remain standard social wallpaper, pursuing internet fame with a discipline and determination that may even be admirable - if only it were in service of something more worthwhile than self-promotion.

In their quest to seem authentic, relatable, and inspiring, the irony is that so many influencers come across as strangely synthetic, the savvy Xiang Xiang being the notable exception. They are less real than one-dimensional sales avatars and more virtual than virtuous. Influencers did not create the system; they merely exploited it. The fault lies not in our internet idols but in ourselves and our willingness to be influenced.

We cannot pin all the blame on the influencers. They are merely responding rationally to social and economic incentives. The root of the rot lies more deeply in our culture's obsession with wealth, celebrity and perfection. Influencers are symptoms of a society that values appearance over substance and money over meaning. Yet even as we decry their vacuity, we cannot look away. We deride their glossy narcissism but quietly envy their seemingly blessed lives. Their allure reflects our deeper insecurities. In a world of bewildering uncertainty, their coiffed confidence provides reassurance. Or they represent a modern-day courtier class, providing pleasurable distractions from harsher realities.

They dominate our feeds because we grant them that prime real estate. Their banality prevails because we click, comment, and crave the lifestyle aspiration they peddle. We can turn away any time we choose.

Do we have the courage and self-awareness to turn away? Or have we become too addicted to the dopamine hit of double-tapping our dreams into being?

The fault lies in ourselves; once we realise this, do we have the will to change?