Mills were once the rural industrial hubs

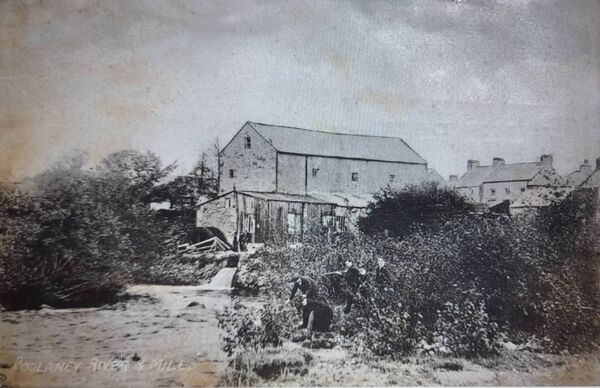

The footprint of Doyle's Mill is still visible on the Mad River in Cloonacool. Picture: Pat McCarrick

Most villages and small towns around the Ox Mountain region had an operational mill at one time or another. My neighbouring village of Cloonacool in south Sligo had no less than three mills that operated at one time or another over the past 200 years.

The passage of time and the introduction of more efficient ways of milling means that such mills have not operated for more than a century at this stage, but they were once a hugely important part of rural life. Their unique mechanics and low running costs were a marvel and an powerful example of old-time creativity and ingenuity.

Most mills used the flow of water to turn a large waterwheel. A shaft connected to the wheel axle was then used to transmit the power from the water through a system of gears and cogs to work machinery, such as a millstone to grind corn.

Watermills were usually built beside streams or rivers, which provided them with a water supply. Very often these supplies were improved by the provision of a mill race to help overcome the problems of different seasonal water levels. Mills were classified by wheel orientation; vertical or horizontal. One was powered by a vertical waterwheel through a gear mechanism as described above, and the other was built with a horizontal waterwheel without such a mechanism.

Millstones were a vital component of any mill and had to be made from special hardwearing stone which was not readily found locally. The Romans imported stone from the Rhine Valley in Germany to England, and during the Middle Ages, the best stone was sourced from France. Millstones were fitted in pairs, the upper ‘runner’ millstone moving against a lower fixed millstone. Stones were usually about four feet in diameter, weighed more than a ton and were geared to turn at about 125 rpm. That took some power.

Jesmond Dene, a public park near Newcastle-upon-Tyne in England, occupies the narrow steep-sided valley of a small river Ouseburn. This park is cared for by a volunteer group who have under their care an old mill which dates back to the early 1700s. As part of their information on the mill, they go back to the origins of milling.

The first documented use of watermills was in the first century BC and the technology spread quite quickly across the world. Commercial mills were in use in Roman Britain, and by the time of the Doomsday Book in the late 11th century, there were more than 6,000 watermills in England. By the 16th century, waterpower was the most important source of motive power in Britain and Europe. The number of watermills probably peaked at more than 20,000 mills by the 19th century.

, by Tom Doyle, gives a detailed account of milling in the region; how they operated and who operated them. It was Doyle’s own forefathers that inspired his research, the family having a long association with milling in both Sligo and Mayo.

Doyle goes on to tell us a bit more about his family heritage, their involvement in milling and the towns and villages locally where they operated. He also makes a distinction between the larger industrial mills and the smaller, more local mills which were a simpler affair.

Doyle informs us of the places where his family once plied their trade and goes on to describe the eventual demise of the local milling way of life. It seems, like most things that pass away, such mills were surpassed by evolving technology and a need for greater efficiency. I imagine at that time little thought was given to the passing of a once vibrant local tradition. It seems in between the canal era and the age of rail, local mills came and went.

Most of the mills the Doyle family ran are now long gone, and some of the buildings disappeared less than 100 years after they were built. However, the mills that survived either adapted or were in very rural regions that were slow to change. These buildings are still in situ, albeit tenuously, and in most cases their watercourses are still intact. Mills are an important part of our industrial heritage and because they were once so common on the landscape, they effectively are considered not rare enough to be conserved.

One of the mills in the small village of Cloonacool was run by a branch of the Doyle family. While the mill has not been in use for over 150 years, its footprint remains by the side of the Mad River, a mountain tributary of the Moy.

The last remaining member of that Doyle family, John, who still lived beside the old mill, passed away in recent years. His passing drew the curtain on a once great local industry.

The Doyle family, and their old mill, are still remembered in Cloonacool village. The Mill Community Café opens every Friday, Saturday and Sunday, 10am to 2pm, and the old millstone from Doyle’s mill stands proudly in the centre of the village as a reminder of bygone days.