John Hume's ideas will always be of relevance

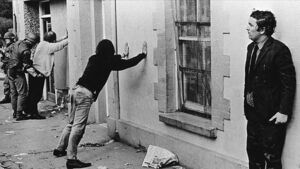

John Hume after being soaked by a water cannon in Derry during a civil rights march in 1971.

I went along last week to see , the play which depicts the last days leading up to the signing of the Good Friday Agreement. It is set around the interactions between the main players: Mo Mowlam, George Mitchell, John Hume, Tony Blair, Bertie Ahern, Gerry Adams and David Trimble.

It’s a great play, and captures much of the hard work, the perseverance, the grit, the rows and the at times farcical stuff that led to the deal. As an example of farce, while Trimble would not shake hands with Adams, there is a scene depicting the two of them meeting one another in the gents – it actually happened. Throughout, there is confusion and moments of crisis and breakthroughs, all captured in its human reality. It was history in action, and like is said of laws and sausages, not all of it will inspire you when you see it done.

The people who come best out of what we see on stage are Mo Mowlam, Bertie Ahern and David Trimble. Mowlam is portrayed as wise and shrewd even though Blair tries to marginalise her; Bertie as a man who knew how to compromise to get the deal; and Trimble as a tough character who knew precisely how much he needed to get to give the deal any kind of chance among his own community.

The play showed Trimble in all his complexity and awkwardness. In his character it also captured those elements inherent within Unionism: lack of trust; truculence; unwillingness to compromise; that sense of superiority and righteousness that comes from centuries of putting the foot on the other fella’s head. But it also showed what it is like to be a people under siege and helps you to recognise, as John Alderdice put it, that it is not paranoia when the other fella is actually out to get you.

Before I went along to see , I had heard that John Hume’s character and significance was played down a bit on the stage. And it was certainly true that while Bertie and Trimble have the firework scenes, John Hume seems central but somehow less important to the drama. I guess that is inevitable 25 and more years on from the Agreement. The following years made the SDLP – and Hume – less important. The man knew it himself. If you build an agreement around two tribes, then the people who can bang the drum loudest for each tribe will eventually take over. That is why Trimble/Hume soon became the ‘Chuckle Brothers’ of Ian Paisley and Martin McGuinness.

That downgrading of Hume’s significance has been ongoing on every front since the ceasefires. But in a strange way the play also made it clear to me that Hume remains at the heart of everything. Not the man, but the ideas of the man, for when you strip away the drama, what the play shows most clearly is that his ideas are what will survive the institutions the Agreement established.

And what are those ideas? They are both simple and profoundly important. That the people of Northern Ireland have to build a shared future together. That you cannot eat a flag and wrapping it around you won’t keep you or those you love warm at night. That you cannot talk about rights and equality all the time without recognising that the other side are entitled to those things too. That in any future plans as to how we organise affairs on this island, it is for the Irish people, north and south, to make that decision together. That in making those plans, coercion, applied by whoever won’t work and will corrupt the side doing the coercing.

By 1998, the leaders of the IRA had come to understand that the disastrous sectarian war that was the Troubles was corrupting everyone who got involved in it and could not be won. Make no mistake, that is why they decided to end it. As a way to help the IRA out of the cul de sac they had driven themselves and everyone else into, Hume handed them his ideas and the platform that grew from them – equality, a shared future, a political means to achieve unity.

The Good Friday Agreement in 1998 was built around those ideas, which were as much principles as a plan of action. The institutions which gave effect to the Agreement have broken down time and again when those on either side didn’t abide by them. But while the institutions arising from the Agreement have started and stuttered, the principles behind the Agreement have endured.

They must endure in the future, whatever it brings. When the Agreement was made in 1998, the balance between unionism and nationalism was considerably more in unionism’s favour than it is now. In another 25 years, that balance will have tilted more in nationalism’s favour, maybe enough to win a referendum in favour of a united Ireland. But then again, in 1998 no one would have predicted that by 2024 there would be a large and growing percentage of people in Northern Ireland who just want to live together in harmony and don’t think all the constant flag waving does one thing that is any use to their life. Maybe in another 25 years there will be many more of those people, and so the question of the union or a united Ireland will seem much less important.

For us down here, our part in all of that is recognising that the identity called unionism exists; that unionists as people are real; that their commitment to being British and to the British monarchy is a valid way to be Irish. If we don’t accept that, then we should stop pretending that we want to unify Ireland and admit that what we actually want to do is conquer it. Whatever else that kind of approach would bring, it won’t bring peace.

Whichever way it goes, the Agreement, great and all it was and is, will probably not exist for all time. Change will change it. The time will likely come when we all – north and south – need new institutions in the future to govern this island. We will then in all likelihood need another Agreement to decide what those will look like. It is when that happens that we will recognise that John Hume’s ideas are the only thing left from that play which will be of relevance. How do we all, people with a different identity, live together on one piece of ground in peace?

And if you still think the way to do it is to find the highest hill and stick your flag on top of it, I especially suggest you go and see the play. When you do, consider Hume less as a character and more as the scriptwriter. For when it came to The Good Friday Agreement, that is what he was, and if it ever needs a sequel, that he will remain.