It doesn't take an expert to know brilliance

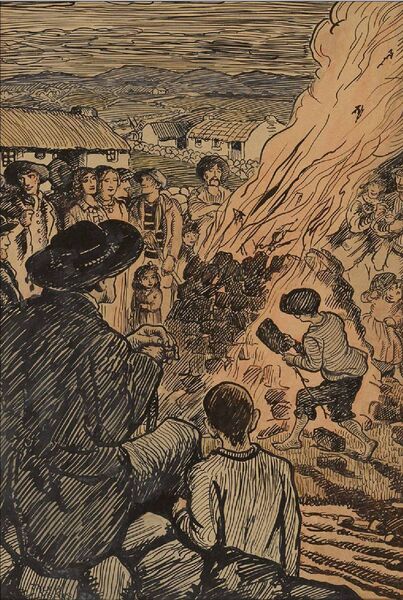

Jack B Yeats painted impressions of scenes which could be interpreted in a number of ways.

Jack Butler Yeats is my favourite artist. His work is always worth seeing. The National Gallery of Ireland is home to an amazing collection of his paintings, and among the many good reasons to visit this summer is that they have recently acquired another.

The painting, which is titled , Croke Park, is now on display in the Gallery. The painting does not directly reflect the events of Bloody Sunday in Croke Park in 1920, but it is believed to be inspired in some way by them. The Gallery says that the tone, setting and title of the picture certainly suggest it.

According to their description, the painting “deepens the gallery’s representation of one of Ireland’s most beloved and influential artists, while offering a poignant reflection on a pivotal moment in Irish history.” The painting has a bit of a history itself, being stolen in the 1990 Dunsany Castle Art theft, before later being recovered. It was acquired by the Gallery last year.

It is thought to be one of Jack B Yeats’s few overtly political works. That said, those who know his works well will have detected some republican sympathies in others in his portfolio, be that a poignant scene after British soldiers opened fire on Bachelors Walk, or one of visitors to prisoners outside Kilmainham Gaol.

I can’t explain my love for Jack Yeats’s work as an art critic would. I can’t tell you precisely what style or school he was in, or how and when his work evolved and changed – though in the simplest terms, his early work was very realistic, his later work more impressionistic. What I can tell you though is how his work makes me feel. My sense is that when you stand in front of a work by Yeats – whether in the National Gallery or in the Model in Sligo, where there are also many fine paintings of his on display – you too will find many feelings summoned up.

You don’t need to know precisely what is going on in his paintings to be moved by them. When I see his painting titled ‘and so my brother hail and farewell for evermore’, I don’t need to know whether it was a sombre reflection on the death of his poet brother, William Butler Yeats – for all I can recall, it may have been painted before William died, though I don’t think so. It is of no significance to me whether the title derives from the work of the Roman poet Catullus, and if it does, what that might or might not mean. The brushwork and technique and the particular style and influence he was drawing on in the work on are, I am sure, very interesting and significant. But none of that matters any time I look at the painting. Because what I see and feel every time is the poignancy of someone dear drifting away.

It is the same with his great painting, . When you look at it, it can take a while before you notice the grieving mother and child, but you don’t need to spot them – or know the title of the painting – to have an immediate sense of what this painting is about. It will overwhelm you with its power from twenty yards. Your reaction to his strident will tell you a lot about how you feel about men of destiny – are you intrigued, repulsed, admiring? The figures stride across the painting at you, and it is obvious that there is, as we might say, a lot going on.

And there are so many more to see in the National Gallery, whether it is a man about to write a letter, the atmosphere of a midsummer’s night, a grand conversation which was under the rose, a famous Liffey swim, many ferries, a morning in the city (don’t miss this one) or paintings and more paintings of horses, and sometimes, almost reluctantly, their riders. Some of his work is playful, some is powerful, all of it is full of meaning. There are so many greats that this little summary list only captures a taste of them.

Jack B Yeats, born in London, but more or less reared in Sligo, was the youngest son of the painter John Butler Yeats and of course the brother of William Butler Yeats. He spent much of his childhood, like his brother, in the care of his maternal grandparents. If William wrote of his Lake Isle of Innisfree and the waters and the wild of his Sligo youth, his brother said that every painting of his “had a thought of Sligo in it”. I don’t think I love his work because of that west of Ireland connection but, as we say, it doesn’t do them any harm in my estimation.

Jack was a visual artist who captured human emotion, who painted impressions of scenes which could be interpreted by an open heart in a number of ways. You require no expertise in art to appreciate precisely what he was trying to do. The colour and vividness produce a humanity and a clarity which is more immediate than any photograph could ever capture.

If you get a chance to pop up the road to the Model Gallery – with very easy parking – in Sligo this summer, you will see plenty of his fine work, and you will see even more in the National Gallery in Dublin. If you have a visitor this summer who might want a day out, you and they will certainly see those hints of the west of Ireland in all the works. But with the work of Jack Yeats, you will see much more than that. You will catch glimpses of truth, of beauty and of insight, and you will experience moments that, as Seamus Heaney said in one his greatest poems, catch the heart off guard and blow it open.