Any hope at all for an Indian Summer?

Month after month of wet weather has created a mounting crisis for farmers across the county.

To my mind the definition of an Indian Summer is the few days we so desperately long for when we have had no summer otherwise. When the months of summer leave us bereft of hot sunny days, we turn to the possibility of a late anti-cyclone floating in to provide us with the few days we feel we deserve. If ever we needed an Indian Summer, we need one this year.

Longing for good weather is part of the human condition, part of who we are, and because of our northwestern position on the map, it is possibly felt more in the Ox Mountains than anywhere else in Ireland.

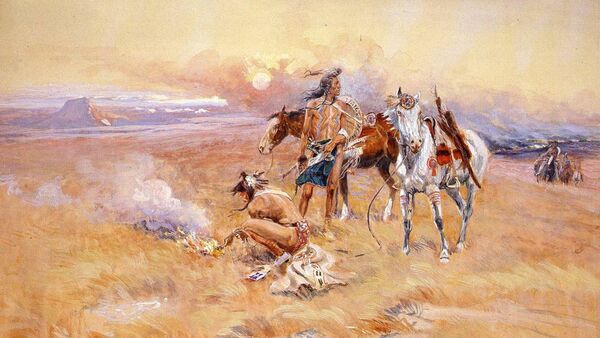

For the record, the true definition of an Indian Summer is, according to the boys in Oxford; Although the exact origins of the term are uncertain, it seems to be so-named because it was first noted in regions inhabited by Native Americans and is based on the warm and hazy conditions in autumn when these First People hunted for the last time before the onset of winter.

The development of agricultural practices about 12,000 years ago changed the way humans lived. They switched from nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyles to permanent settlements and farming. It is fair to say that from that day to this, the weather took on a renewed importance for all mankind. Before that, it was up to nature itself and the animals and fruit it provided. From then on, the weather and how it behaved was our first concern, it became a matter of life and death. According to , it may well have been the weather itself that tempted us into the farming way of life in the first place.

“There was no single factor, or combination of factors, that led people to take up farming in different parts of the world. In the Near East, for example, it’s thought that climatic changes at the end of the last ice age brought seasonal conditions that favoured annual plants like wild cereals.”

I often thought it was just the Irish who obsessed about the weather; will it rain enough, would we ever get a few days for the hay or a decent stretch to ripen the oats? The truth about our dependence on the weather, and our food supply, is that every farmer that ever lived has had the same worry. The biblical flood, the plague of locusts, the dustbowl and the dreaded droughts of Africa have all undone humanity at some point and showed us, God, or no God, that the weather is everything.

They say it was the weather that made the Irish the easy-going race they are reputed to be. The theory behind that was, if the day came bad, we could always wait until tomorrow to start the job at hand. This gave the impression that we were a more relaxed form of humanity, with lots of time on our hands. There was more than a grain of truth in the theory but the days of easy-going farming are fast disappearing. Farming is now often a race against time; bank loans, cash flows, not to mention the weather. Whether these pressures are due to changes in farming practices or changes in climate, the result is the same – farming families living on the edge and individual farmers veering dangerously close to depression.

Ronan McGreevy, a news reporter with the wrote in an article in March this year of the challenges facing a tillage farmer in Co. Meath. His piece began with the bold headline, “Wet weather leaves farmers in despair: ‘I have never seen it this bad. Everything is compounded together’.”

“Nine months of wet weather is creating a mounting crisis for Irish tillage farmers. After one of the warmest and driest Junes on record, it started raining in July and has barely stopped since. The knock-on effects have been huge. Beef and dairy farmers have had to keep their cattle in longer because of the soggy ground so there is a fodder shortage and the grass is not growing the way it should be, but tillage farmers have it worse.

“The McCormacks have been involved in tillage in Co Meath since the 1960s when Eddie McCormack arrived from Co Mayo and started with 23 acres. Their holding has now expanded to 280 hectares (600 acres) of some of the most fertile land in the country.”

The story is similar for dairy farmers throughout the country and with winter just a few short weeks away, it seems 2024 will be remembered as one of our worst, weatherwise. Farmers in the Ox Mountain region are also feeling the effects, with poor summer grass growth and with few descent opportunities to save enough winter fodder.

According to the US publication, , there are several criteria for an Indian Summer, maybe more accurately described as a Native American Summer. I cite this criterion here not to make readers feel worse, just to reflect on possibilities.

“It’s a period of abnormally warm weather occurring in late autumn between St Martin’s Day (November 11) and November 20, with generally clear skies, sunny but hazy days, and cool nights.

“The time of occurrence is important: It occurs after at least one good killing frost but also before the first snowfall; preferably a substantial period of normally cool weather must precede this warm spell. As well as being warm, the atmosphere is hazy or smoky, there is no wind, the barometer is standing high, and the nights are clear and chilly. A moving, cool, shallow polar air mass is converting into a deep, warm, stagnant anticyclone (high pressure) system, which has the effect of causing the haze and large swing in temperature between day and night.”

Native Americans would routinely use this brief period of warm autumn weather as an opportunity to increase winter stores. An Indian Summer was their last chance to capture bounty before winter set in.

This year, as deadline after deadline passed, without a break in the weather, the onset of winter now looks more depressing than ever. We thought the weather might take up in July, then August and, as schools reopened, we hoped September might come good. Whatever the origins of the Indian Summer, oh, how we would love a few sunny autumn days before winter sets in – just a week or two, to dry the land and maybe get a pinch of late silage.

Glenn Miller