A century after independence, this is Mayo's moment

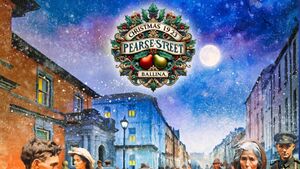

Conor McGuire's wonderful illustration of Pearse Street in Ballina a century ago, which features on the front cover of this year's Western Star.

I hope you like the recreation of a Christmas scene of Pearse Street in 1923, gracing the magazine cover and reprinted with this article. The line of the buildings and the skyline stretching to the post office have mostly stayed the same. Only the costumes and means of transport betray its vintage.

However, suppose a stranger were to travel south and stand on the peak of Nephin or the Partry Mountains on a clear day and gaze out across the patchwork quilt of fields, bogs and lakes that make up County Mayo. In that case, it's easy for them to imagine that life here has changed little over the past century. The small towns and villages, connected by narrow winding roads, appear untouched by time. Many natives continue to work the land and fish the sea as their ancestors did. This vista is the romantic Ireland of postcards and flowery prose, a throwback to an older, more straightforward way of life.

But we natives know that beneath the surface, you'll find a county that has undergone profound and often painful upheavals in the last 100 years. Though the population has fluctuated, Mayo has been reshaped by the forces of economics, politics, technology and social change. It's a story of conflict and loss, of exodus and renewal. The one constant has been the unyielding land itself, sculpted over aeons into a landscape of untamed and haunting beauty.

In the tumultuous years after independence, Mayo became a byword for remoteness and stagnation. The disparaging moniker 'Culchie', reputedly derived from 'Kiltimagh', denoted a rural and culturally deprived arrival to the sophistication of larger urban centres. Mayo was the archetypal forgotten 'backwater' – remote, conservative and stubbornly resistant to progress. By the 1950s, the county had the highest rates of emigration and lowest per capita income in the country. For many, the only route out of grinding rural poverty was a boat to Liverpool or New York. Several small islands off the coast were abandoned as the Government resettled residents on the mainland.

The causes of emigration were complex but rooted mainly in the county's geographical isolation and over-reliance on farming. Land redistribution post-independence never translated into extensive farm holdings, so farms remained small and family-orientated. Fishing also declined when the new State failed to provide subsidies or protection from foreign trawlers.

For all our lofty rhetoric about a Gaelic revival, the Irish language made few inroads in this English-speaking part of the West. Those pockets of the Gaeltacht that remain are today threatened with obsoletion, and no amount of Gaelic tuition seems capable of arresting that downward trajectory.

By the 1960s, from the progressive heights of Dublin 4, Mayo had become shorthand for all that was wrong with conservative, inward-looking, post-independence Ireland. In his famous 'diary' chronicling Irish life, the irreverent English journalist H.E. Bates described it as a "sad, grey place" trapped in the past – "no gaiety, no fun, no joy at all". He painted a misguided picture of dour, repressed people leading joyless, circumscribed lives under the deadening weight of the unchanging tradition. The portrayal is deeply at odds with the happiness and peace that characterised my 1960s childhood and the contented adults who populated that Ballina universe.

But the winds of change that swept across Ireland in the late 20th century could not pass Mayo by indefinitely. A combination of rising education levels, social mobility and migration from - and to - Dublin slowly began to erode its insularity. By the 1980s, the previously unexamined conservatism was waning as a new pluralism affected long-held practices and once cherished conservatism. The Church lost its status as an unimpeachable moral authority amid abuse scandals.

Mayo has not entirely shed its reputation as a bastion of traditional values but has liberalised socially and culturally over the last few decades. One sign of this shift was the vote to legalise same-sex marriage in 2015, indicating changed attitudes towards LGBTQ+ rights even in rural areas. The influence of the Church has unquestionably declined, though Mayo remains Ireland's most Catholic county, with over 90% of the population still identifying as Roman Catholic. We haven't entirely thrown out the ecclesiastical baby with the muddied bath water.

Emigration is no longer seen as the only route out for young people, thanks to increased employment and educational opportunities. Multinational companies have brought precious jobs to former economic blackspots. Nostalgia for a simpler past persists in parts of Mayo, but there is also intense pride in its reinvention as a more progressive, outward-looking place.

Tourism has replaced agriculture and fishing as the main driver of economic growth. The raw, overcast beauty of Mayo's landscape has become its prime asset rather than a barrier to modernisation. Areas like Westport and Ballina have been reimagined from the poor cousin of Killarney into cosmopolitan tourist destinations, tapping into the rise of staycations, outdoor pursuits, food tourism, and the Wild Atlantic Way.

Of course, the glossy brochures telling tourists to 'Escape the ordinary!' conceal as much as they reveal about the reality of life for many here. Mayo is still one of the most disadvantaged parts of Ireland, with significant pockets of unemployment, poverty and depopulation. It would be wrong to portray it as transformed beyond recognition. But there are signs everywhere of a place awakening slowly from its uneven 20th-century slumber.

The changes can be seen in the influx of outsiders, lamented by some but undoubtedly bringing new blood and fresh perspectives. Eastern Europeans now work in our factories and family-run businesses. You're as likely to hear Polish and Arabic as English spoken on Ballina's streets. The blow-ins include artists and entrepreneurs drawn by the landscape and slower pace of life as much as the cheaper cost of living.

Cast your eye along the shoreline, and you'll see the vast wind turbines producing renewable energy harnessing the ever-present Atlantic winds. These altered vistas are a world away from the subsistence farming of old. Look at the primary schools where pupils learn their ABCs through Gaeilge, reflecting the partial revival of Irish, which is much more visible than 50 years ago. Listen to the accents of the people drinking in the pubs of Ballinrobe and Ballina - that blend of rolled Rs and flat vowels so characteristic of the West of Ireland but increasingly infiltrated by Dublin visitors and foreign inflections.

The forces reshaping Mayo and shaking its inhabitants from their cultural homogeneity are essentially the same that have transformed rural life across Europe in recent decades – increased mobility, education, secularisation, relative prosperity, inward migration and technological change.

Some natives feel threatened and unsettled by the pace of change, foreboding a gradual dissolution of Mayo's distinctive character, something to be mourned rather than celebrated. But we can preserve our unique character, our 'Mayoness'. These detractors lament the loss of an unchanging way of life, of comforting, familiar culture and intergenerational community spirit, forgetting the terrible historical bleed of emigration that reduced whole townlands to dereliction. But for the more forward-looking denizens of Mayo, the opening up of horizons closed for so long is cause for optimism about our future as part of a more progressive Ireland while retaining a quiet pride in the old ways. Assimilation, not discrimination, should be our guiding principle.

So, I will take another look from those mountain peaks as the shadows lengthen and evening approaches. The golden light that bathes the patchwork fields etched over centuries by stooped figures with spades or steering shiny tractors remains unchanged. A thin wreath of peat smoke still rises from many a chimney. The low rays glance off whitewashed cottages juxtaposed with architect-designed new builds, clustered around villages suddenly revitalised by newcomers seeking a better life balance. In the velvet blue haze from the Moy estuary, Bartra Island floats like a sleeping sea turtle, unworried by the passage of time.

We can project our dreams and ideals onto this landscape – see it as an embodiment of unchanging Irish tradition or a backward relic of the past awaiting modernisation. But the reality is more complex. Global currents now reshape County Mayo, but its essential character can endure and adapt. Our evolving story challenges lazy stereotypes of Ireland's West as either an unchanging rural idyll or a benighted backwater. One hundred years on from independence, this is our moment. Our county and its natural treasures are the envy of more challenged counties under siege due to a lack of planning and available spaces. We can boast sweeping vistas and virgin soils, and we have the opportunity to plan appropriately.

Like the charming light over Nephin at sunset, Mayo is a constant and ever-changing place. Our lives and outlooks are shifting gradually like the ocean tides that pulse through Killala Bay. Beneath the surface, the currents are slow-moving and deep. To understand Mayo is to embrace those seeming contradictions - change and continuity, loss and renewal. Its true character lies in that uneasy balance of past and present. As the Celtic dawn of 1916 stretches into evening, the history and identity of Mayo need not recede into myth and mystery. Instead, we can look ahead, strengthen our enviable cultural identity and embrace the enriching stream of change. It has always been so; for centuries, our county has been home to natives and foreigners, and nothing of value needs to change beyond recognition.