The curious case of a Mayo police conspiracy

The picturesque seaside village of Mulranny was the setting for the remarkable case.

As he surveyed his new surroundings on Inishkea North, Constable John Curtin must have been acutely aware of the consequences of speaking out against a superior in the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC).

Though one of the most breathtaking locations in Ireland, the remote islands of the Mullet Peninsula would not have been a destination of choice for policemen in 1898.

Locals had long had a distrust of authority and had lived pretty much their own independent lives. That distrust would have certainly extended to anyone in the RIC, whose main role appeared to be the clamping down on poitín distilling on both islands. It was a key source of income on the Inishkeas.

And it was not like being stationed on the mainland, where you could easily go elsewhere to get away. The mainland was eight kilometres away across often rough seas, and being marooned for weeks at a time due to unsafe boat conditions was not uncommon.

Curtin was like Father Ted, banished by the authorities to a faraway island. Unlike Father Ted, who was on the fictional Craggy Island due to financial irregularities, Curtin’s case was very real and undoubtedly appeared to be because he dared call out the abuse of power by a sergeant in Mulranny, his immediate superior.

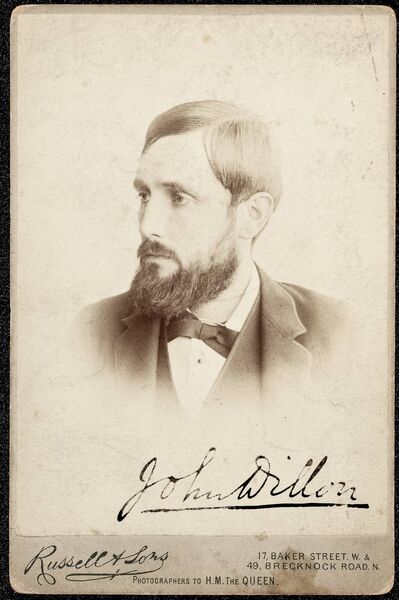

He had Michael Davitt, John Dillon and William O’Brien on his side, and his treatment was highlighted extensively at the House of Commons in London. Over a century later, what became known as the Mulranny police conspiracy is a compelling tale of a miscarriage of justice, a cogent example of the distrust Irish nationalists felt towards British authorities in Ireland and a case which enraptured the country.

The railway station opened in Mulranny in 1894 while the village’s landmark hotel, adjoining the station, followed three years later. However, despite these developments, life in Mulranny was hard and bleak. The railway only provided an easier route for emigration to the United Kingdom and USA for many locals and poverty rates were high.

It was Mulranny that was the first posting for a young John Curtin. The Cork native passed out from the constabulary depot in Phoenix Park. He came from a nationalist background – his cousin, O’Neill Crowley, was a noted Fenian.

Curtin came to the west Mayo village, a place of 'fine scenery and romantic surroundings’ in 1896 and arrived in a community where land activism was on the rise. The campaign for tenants’ rights had been ongoing since the 1870s, particularly since the establishment of the Land League in Castlebar in 1879 by Michael Davitt, James Daly and Charles Stewart Parnell.

Mulranny was like many other locations throughout the island where the RIC and, in many cases, the local landlord, were viewed with suspicion and contempt by local land reform activists. As it turned out, it would appear they had particularly just cause for such suspicion in Mulranny.

Writing in an explosive letter in the in 1902, Curtin detailed the type of work he and his colleagues had to undertake. They often had to initiate a raft of petty charges as ‘an apology for our existence’, such as charging people for coming home drunk from the fair, publicans who served drink after hours or for farmers who did not have their names painted on carts.

But, in a harbinger of what was to follow, Curtin claimed many of his colleagues were not adverse to ‘put up jobs’.

“Such base tricks as concealing poitín... on some poor peasant’s premises without his knowledge and then having him arrested, convicted and imprisoned whereby the unscrupulous author of the plot received the six or seven dollars (sic) reward given by the Government in such cases,” wrote Curtin.

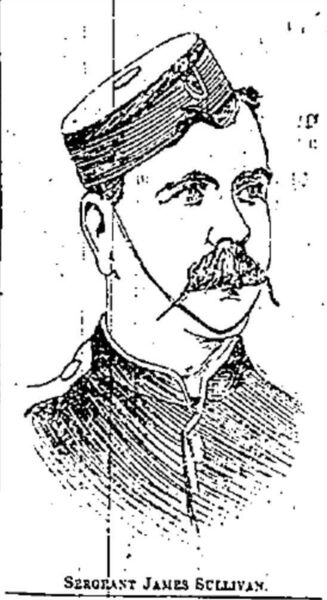

He wrote about one superior, Sergeant James Sullivan, doing this to a ‘personal enemy’ called Mulgrew, ‘placing illicit whiskey in the unfortunate man’s house and then coming and seizing it and accusing him’.

So tensions between the rule of law and locals in Mulranny were particularly high. They would escalate to an entirely new level in 1898.

Campaigning for greater tenants’ rights was growing.

It was the 100th anniversary of 1798 and in January 1898, a new tenants’ organisation, the United Irish League (UIL), was established in Westport. Some of its key figures were Michael Davitt, William O’Brien and John Dillon. The president of its West Mayo branch was Newport man John McHale.

The UIL gained a foothold in Mulranny thanks to people like the O’Donnell siblings, Patrick, Kate and Peter. Perhaps because of a fear of escalating tensions in the village, the RIC presence in Mulranny was doubled from four to eight officers early in 1898, John Curtin and Sergeant Sullivan still among them.

One of the first actions the UIL initiated in Mulranny was to boycott the local landlord, Robert Vesey Stoney of Rosturk Castle, whom Curtin described as a ‘notorious character’. The boycott extended to anyone who worked for him. To boycott was an established tactic by then in the county where the term was coined.

Charles Stewart Parnell urged locals to put Ballinrobe estate manager Captain Boycott into a ‘moral coventry’ in 1880 and Stoney and his staff were put into a similar ‘moral coventry’ in 1898.

The UIL said Stoney and any of his staff were to be ostracised in the community and refused service in pubs and shops. One of Stoney’s workers, Martin Kelly, was determined not to be dictated to and he became centrally involved with what happened.

On April 14, 1898, local UIL activist James Kelly received a letter signed ‘John MacHale, UIL President’. James Kelly was Martin Kelly’s second cousin, but there was a long-standing feud between the families.

The letter said, ‘as you are aware, Martin Kelly is gone back to the bastard Stoney’ and instructed James Kelly ‘to go with some of the boys’ to Martin Kelly’s home that night, to tell him ‘he’s working against our cause’ and James Kelly was advised to ‘blacken your faces’ and ‘watch for the police’. The letter also said ‘burn this for fear of danger’ and ‘don’t bring any men but ones you can trust’.

Speaking about that letter in the House of Commons in June of 1899, Michael Davitt said: “There could be only one purpose indicated by that communication, that was the carrying out of a moonlighting outrage, which might probably result in loss of life.”

James Kelly did not act on the letter – he could not read very well so he took the letter to a neighbour, John Gibbons at Newfield, Mulranny, whose suspicions were aroused, and Gibbons contacted MacHale, who came to Mulranny two days later, strenuously denying the letter was written by him.

But not just that - when MacHale and other local UIL members saw the letter, they claimed to recognise the handwriting. They made an explosive accusation - that the writer was Sergeant James Sullivan, the policeman in charge at the Mulranny RIC Barracks.

MacHale and his UIL colleagues set about trying to copperfasten their case by getting copies of Sullivan’s writing. Kate O’Donnell even took to writing love letters to him in the hope of receiving an incriminating response! That effort was unsuccessful but in 1902 John Curtin revealed that Sullivan heard of their efforts and ‘took the alarm and went about gathering up and destroying every scrap he had written’. Despite Sullivan’s efforts, the UIL got their hands on five copies of his handwriting.

“The necessary specimens were secured and loud were the oaths that rang through Mulranny barrack when that burly police forger realised that he was outwitted,” wrote Curtin.

With their evidence collected, John MacHale then initiated court proceedings against Sullivan for criminal libel. After failing to get sent forward for trial at Westport Petty Sessions, they took a private prosecution and were due before court in Castlebar in July of 1898.

It was, understandably, the talk of the land and commanded huge coverage both in the national print media and in local newspapers.

Little did John MacHale and his UIL colleagues know but there was a constable stationed in Mulranny who was not one bit surprised by any of this and stepped forward to give evidence against Sullivan. Curtin described Sullivan as one of ‘a great many conscienceless villains’ in the RIC. When he heard the specific details of the letter, John Curtin felt it was certainly another ‘put-up job’.

“On the night proposed for the visit of the black-faced vigilantes to Kellys, Sergeant Sullivan and three other policemen, all armed to the teeth, left our barrack and stealthily went in a roundabout way to the rear of Kelly’s house, where they ambushed in a thicket, and there they watched and waited from 10pm till the break of day when they returned disappointed to the barrack,” wrote Curtin.

Curtin would tell MacHale’s legal team in court that he had gone and looked at the logs for the night in question and saw they had been altered to say the group had, instead, returned at 11pm. It was crucial evidence but it was Curtin, and not Sullivan, who found himself in the crosshairs with the RIC top brass.

Mr Aulton, the district inspector of constabulary, whom Curtin said ‘was anxious to shield his subordinate at all hazards’.

“Bizarrely, he asked me: ‘And why did you set yourself to find out these things?’”

The consequences of speaking out were not long in arriving. Curtin said that on July 9, 1898, in Mulranny Barracks, Sergeant Sullivan told him he was being transferred to the Inishkeas.

John Dillon compared it to being sent to Devil’s Island, the notorious French prison colony. Michael Davitt did not hold back in his criticism of the treatment of Curtin.

“(He) was banished from Mulranny out into the Atlantic, in a wild island called Inishkea, in order to mark their disapproval of his conduct in showing a willingness to assist the course of justice,” he said.

Many key witnesses also faced a raft of minor charges ahead of various sittings of the case.

James Kelly was charged with being drunk in public two days before a hearing in July 1898, while Neil O’Donnell, father of the three UIL activists in Mulranny, was arrested the next day for allowing his animals roam on the public road.

In September 1898, in Westport, John McHale was arrested and charged with being drunk in public. His efforts, while in custody, to get a doctor to come to the police barracks to testify to his sobriety, were unsuccessful.

The following year, ahead of a civil case on the matter, Neil O’Donnell was charged with walking his dog without a muzzle and for displaying a harp in his pub on St Patrick’s Day.

Michael Davitt was clear in his view as to what was happening.

“They [RIC officers] harassed other witnesses pending the trial at Sligo, and left no expedient untried to intimidate those who were proceeding against Sullivan.”

The first criminal trial got underway in Castlebar in July 1898. MacHale’s legal team brought in two experts in handwriting from London, one of whom, Thomas Gurrin, was frequently employed by the Home Office in London as an expert.

It was clear that it was not just a local issue but a case that the UIL felt would demonstrate the institutional biases Irish nationalists and land reform activists were up against. Both these expert witnesses gave evidence that the handwriting on the letter received by James Kelly was, indeed, that of Sergeant James Sullivan.

Curtin, stranded on Inishkea North, could not make it to Castlebar to give evidence. However, the case was adjourned to a full hearing of the Connacht Assizes in Sligo in December 1898. This time Curtin would be in attendance.

He gave evidence of the planned ambush at Martin Kelly’s, their disappointment when they were unsuccessful, the change to the logs for the night and Sullivan’s nervous and angry behaviour about his handwriting.

It appeared to be a strong case against the RIC man but the jury, after hearing MacHale’s legal team prosecute the case, decided they did not need to hear the defence case at all and ruled Sullivan was not guilty. The Crown Prosecutor in the case was Malachy Kelly, the Crown Prosecutor for Mayo.

“If ever there was a miserable farce, showing the pitiable injustice and corruption of English government methods in Ireland, it was that trial,” wrote Curtin.

He said ‘while the Crown was supposed to act as prosecutor, the Crown officials, both lawyers and police, were on the side of the accused forger’.

“Knowing that conviction of Sullivan would be a nationalist victory, Malachy Kelly, the Crown prosecutor for Co Mayo, while pretending to prosecute, carefully packed the jury box with men who were prone and sure to bring in an acquittal,” wrote Curtin.

He was far from the only one with that view.

Back in Mulranny, the conclusion of the trial in Sligo and Sergeant Sullivan’s acquittal led to celebrations among the police, according to the , but the paper, sympathetic to the UIL’s position, said such ‘festivities’ might be ‘just a little premature’.

John MacHale and the UIL were not going to relent. He turned to the civil courts, where he sued Sergeant Sullivan for libel. That took place in the High Court in Dublin in May 1899. MacHale needed the unanimous backing of every member of the jury.

The covered every day of proceedings in substantial detail, reporting that the case had ‘excited the greatest public interest’ and the court was, every day, ‘crowded’.

Thomas Gurrin once again attended and told the jurors that he had viewed the James Kelly letter and five examples of Sergeant Sullivan’s handwriting. He said the letter to James Kelly was ‘written in a disguised hand’ and that he ‘formed the opinion’ that it was written by the same person who wrote the other five specimens.

Under cross-examination, he said there was no great expertise required for this conclusion, that ‘it will be obvious to anyone who looks at these letters who it was who wrote them’.

John McHale was a lot closer to success in the civil case but the high bar of requiring every juror to side with him proved too big. Ten sided with him, but, crucially, two did not, and Sullivan got off.

Following the conclusion of the criminal trial in Sligo and the subsequent civil trial in Dublin, the Mulranny police conspiracy excited passionate exchanges in Westminster.

It was even compared to the Dreyfus Affair in France, a seminal miscarriage of justice case which rocked the Third French Republic both before and after the Mulranny police conspiracy. That concerned the wrongful conviction of a French army officer, Captain Alfred Dreyfus, and the subsequent suppression of new evidence which would have vindicated Dreyfus.

Certainly, there was no doubt among Irish MPs about the guilt of Sergeant Sullivan and the collusion of the British establishment in Ireland in ensuring there would be no conviction.

Reports in the and the in May and June, 1899, vividly portray the depth of the outrage Irish nationalist politicians felt over the Mulranny police conspiracy and how it confirmed much of what they had long been arguing about the partisan administration of law and order in Ireland.

In a Westminster exchange, reported in the of May 6, 1899, Michael Davitt, in his role as MP for South Mayo, asked how could it be that in Sligo, with a population of 89,000 Catholics and 8,500 Protestants, the jury was ‘composed exclusively of Protestant Unionists’ and that Crown Solicitor, Malachy Kelly, ‘who was supposed to be conducting the prosecution’, challenged every Catholic juror who came to the box. The matter was also brought up in the House of Lords later that month with Lord Coleridge arguing strongly against Sergeant Sullivan.

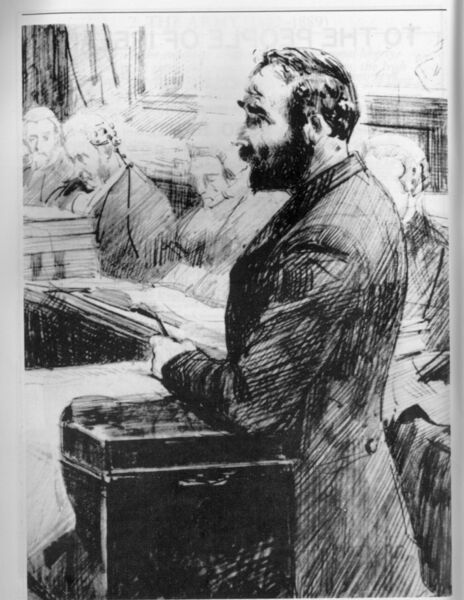

It returned before the House of Commons in June, with lengthy and passionate exchanges and accusations from Irish and, indeed, English MPs critical of the handling of the case while Attorney General for Ireland, John Monroe, stoutly defended the State’s behaviour. The extensive report in the on June 23, 1899, is visceral as you picture giants of Irish politics like Michael Davitt, John Dillon and others decrying what had happened in this case.

Davitt said the trial was ‘a screaming farce’ and accused agents of the State of having resolved to ‘shield this officer from justice, and protect him from the consequence of his own act’.

He was critical of Malachy Kelly, who he said had made an ‘intimidatory speech’ in a Mayo court case prior to the start of the Mulranny saga, where he ‘attacked’ MPs John Dillon and William O’Brien and that instead of rebuking Kelly’s statements when attention was drawn to it in the House of Commons, the Chief Secretary for Ireland, Gerald Balfour, a Tory, had ‘endorsed and applauded the language’.

He charged that such comments against leading members of the UIL were the spark to legitimise the behaviour in the Mulranny case, claiming the whole episode was a conspiracy on behalf of the policemen, landlords and Crown prosecutors in the west to involve the United Irish League in crime.

The Attorney General described Mr Davitt’s comments as ‘scandalous’, saying public officials had ‘courageously and very honourably discharged their duties under great difficulties in Ireland’. He claimed Sergeant Sullivan had ‘become obnoxious’ to the UIL ‘because some of the objects of the League were criminal’, citing boycotting and claimed John McHale was ‘not apparently a very well-conducted man’.

He cast some doubt on the strength of the handwriting evidence and was then asked if the expert used in the case was the Government’s own Home Office expert. “I believe he was,” replied the Attorney General to nationalist cheers.

In the same Westminster exchange, John Dillon was critical of the treatment of John Curtin.

“When it was found there was a prima facie case against Sullivan, the Crown should have kept Curtain as above suspicion, but instead they banished him to Innisheen (sic, Inishkea), a sort of Devil’s Island, out in the Atlantic,” he said.

Describing how an all-Protestant jury was empaneled from a county which was 90 percent Catholic, Mr Dillon said that: “Even in the annals of the administration of justice in Ireland this case was absolutely without a parallel.”

He described it as: “A scandalous and deliberate case of jury packing in which the solicitors for the defence and for the prosecution acted in collusion, with the result that a jury was produced of Unionists and Protestants - men who presumably were partisans of the accused, and enemies of the organisation which had originated the prosecution against Sullivan.”

Mr Dillon said the case was stymied at every turn in favour of Sergeant Sullivan, including the first time it appeared before a court, before Lord Sligo at Westport Petty Sessions, who refused to send it forward for trial. Eventually, private prosecutors had to take it on from the state prosecutors, despite a prima facie case, he argued.

Renowned English Liberal MP Henry Labouchère spoke about the fact that all the jurors were Protestant despite County Sligo being 90 percent Catholic.

“Chance did not play such tricks as that, unless somebody interfered with chance,” he said, adding that if such things were allowed in Ireland, he was ‘not surprised that there should be distrust of the administration of the law’.

His Liberal Party colleague, Charles Hemphill, was critical of the ‘long-existed’ system of ‘jury packing’ in Ireland and that a ‘want of confidence’ in the administration of criminal law in Ireland was ‘one of the causes which led to political disturbances’.

Long-serving nationalist MP TP O’Connor made the comparisons with the Dreyfus Affair, describing the ‘startling analogy’ between the two in terms of how the prosecutions were conducted and ‘a sham trial in each’.

“The system of Government in Ireland was symbolised by Sullivan. The Government stood by him, because they knew that in defending him, they were defending their own corrupt system,” said TP O’Connor to cheers from his nationalist colleagues in the chamber.

James P Farrell said the Attorney General had ‘betrayed a good deal of feeling which might fairly lay him open to the charge of partisanship’ in his first reply to Mr Davitt, adding the Mulranny case ‘was only one instance of the many which led the Irish people to hate and detest the administration of the law in Ireland’.

North Cork MP James Flynn ‘regretted that the Attorney-General had displayed himself as so bigoted a defender of one side in a subject in which he should have endeavoured to stand impartial’.

MP for Derry North JG Swift MacNeill, a Protestant nationalist, described the administration in Ireland as having ‘sunk knee deep in pollution and corruption’, claiming Dublin Castle (the seat of British administration in Ireland) ‘charged the dice in favour of their own criminals’.

Referring to the comments made by Michael Davitt about Malachy Kelly’s ‘intimidatory speech’, he said Kelly had used threats against UIL members ‘and promised the protection of the Government to those who were opposed to it’.

“What was the result of Mr Malachy Kelly’s warning? The result was Sergeant Sullivan’s forged letter. If Sullivan had succeeded into dragging people into a crime he would probably been made a District Inspector or a Resident Magistrate, as a reward for his action,” he said.

MacNeill was heavily critical of Malachy Kelly’s presence as the chief prosecutor in the Sligo trial.

“Mr Kelly had every possible motive and desire not to get a conviction against Sergeant Sullivan... The whole action of the Crown in this matter was most disgraceful... The case might be put down as a standard case to illustrate the villainy of Irish administration,” he charged.

The case was a severe blow to any standing of the RIC and a real shot in the arm for the UIL. It demonstrated the irreparable chasm that was ever-widening between the British establishment in Ireland and Irish nationalists, which would play out very clearly in the next two decades.

Sergeant Sullivan was transferred from Mulranny not long after and became embroiled in another controversy in 1902, when he was accused of assaulting a married woman. He was cleared of that charge, explained George Wyndham, the then Chief Secretary for Ireland, in response to questions from MP for East Mayo, John Dillon in the House of Commons.

Wyndham said officers of the Crown had ‘no hesitation in saying that there was not the slightest case for a prosecution’ and that the charges were ‘fabricated’.

Irish nationalist MP James O’Connor replied tongue in cheek: “The charges against policemen in Ireland usually are fabrications.”

Meanwhile, John Curtin’s time in the RIC did not last long.

“When that farce of a trial was finally over, I took off the uniform of the Royal Irish Constabulary and discarded it for good with spectacular demonstration impressive to all concerned. It is a neat and natty uniform, but some very mean men are wearing it nowadays in Ireland,” he wrote.

He emigrated to the USA in 1902 but, before he did so, he wrote the letter, published in the on October 4, 1902.

Long before the term came into popular usage, John Curtin was a whistleblower, willing to call a halt to what he witnessed, even if there would be serious consequences for his career in the Royal Irish Constabulary.

He rocked up in Chicago where he studied law and according to a report in the in 1913, he was a leading member of the bar in the Windy City. That report centred on Curtin giving a recount of the Mulranny police conspiracy to members of the Mayo Men’s Association of Chicago.

Over a century on from then, it remains an amazing case.

- If you want to read more articles like this, pick up the , available in all local newsagents.