‘Awareness of your mortality puts a lot of things in life in perspective’

Tommie Gorman relaxing near his home at Kelltstown, Co Sligo. Picture: James Connolly

Tommie Gorman recently launched his autobiography, entitled .

He began his career in journalism as a reporter at the Ballina-based before landing the role of North-West correspondent with RTÉ in 1980.

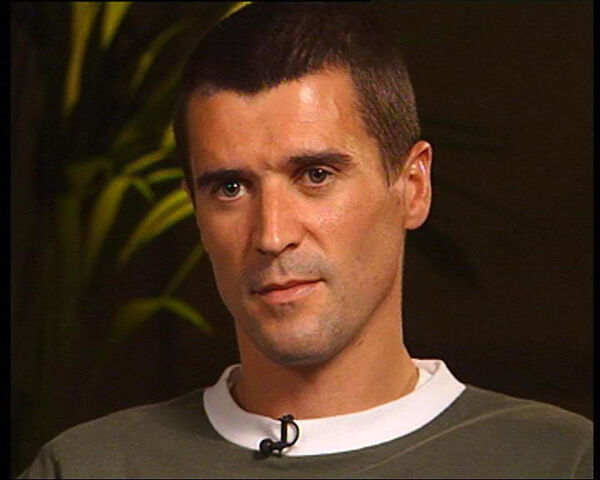

Over the next four decades, Tommie became a familiar presence in Irish homes, known for his coverage of Europe and Northern Ireland, as well as his unforgettable interviews with controversial figures including Gerry Adams, Roy Keane, Ian Paisley and Arlene Foster. While revelling in his life as a journalist, he was also coping with the cancer diagnosis he received in 1994 and seeking ways to access life-saving treatments for patients who shared his rare form of the disease.

The Sligo native has fond memories of his time in Mayo. He was recruited by the legendary journalist John Healy as the newly formed went head-to-head with the in a newspaper ‘grudge match’ in the late 1970s.

“The Mayo roots were kind of important. John Healy gave me the start. John Healy hired me when I was in the School of Journalism in Rathmines. They were starting a new newspaper in Ballina, John Healy and Jim McGuire. I went up to John Healy’s house in Rathmines. It was a two-year course and I was halfway through the second year. Healy suggested that I come to work with him. Healy and McGuire were known as the terrible twins of provincial journalism! They were quite a force. It was a grudge match with the . They were setting up a new newspaper, , and they thought having a Sligo arm to it might help their circulation.

“The paper was based in Garden Street in Ballina. The directors were Cathal Duffy from Castlebar, Ernie Caffrey in Ballina, Paddy Smyth, the father of Smyth’s Toys in Claremorris and there was a chemist from Belmullet called Paddy Lavelle. They were the investors in the paper. It was a school of hard knocks and probably more than that because it was a real dog-eat-dog existence. The cover price paid for the printing so the only way it made money was through advertising,” explains Tommie.

The emergence of the sparked an intense rivalry.

“It was competitive but it wasn’t bitter. You made friendships with journalists from the other papers. Geri Ward, was starting out with , she subsequently became a barrister, the likes of photographer Henry Wills, they were our friends,” said Tommy. “One of the big things the wanted was to have better quality pictures because it had more modern stuff and was going to be printed in the . But the saw it coming and invested in new technology. Once they saw a rival coming they did a spring clean and it showed,” he added.

Tommie became firm friends with a young notes correspondent for the who went on to become an All-Ireland-winning GAA manager.

“One of the great friends I made during that time was a guy who did the notes for us in Ballaghaderreen, that was John O’Mahony. I became friendly with John and later in my RTÉ life, I used to do the training videos and video analysis for his different teams. So I worked with him when he was with Mayo - quietly, all in the name of friendship, there was no money involved. I worked with him in Leitrim when they won the Connacht championship and then I worked with him in Galway when they won two All-Irelands.”

In the book, Tommy lists all the people he served alongside in the . There are also tales of a few mishaps along the way!

“There is a good story about a printer called Michael Hegarty. John Healy went to America with Charlestown GAA club, they were playing over there. They went to this function one night and they were given this lump of money by Mayo guys over there who had made good in the construction industry. Healy was dictating his copy over the phone. I knew Michael Hegarty would be printing it and Michael had been giving out that this was a junket to the States. So I put in brackets, ‘More drinking money for the lads, Hegarty!’

"I knew when he saw it he would laugh about it and take it out of the copy. But Hegarty wasn’t on duty that day. A girl called Laura who was a touch typist was the setter and Laura didn’t pass any attention to this and she printed it. We had nobody checking the proofs so when the paper came out, you had the story, ‘And while in Chicago, such brothers formerly of Ballaghaderreen who made good in the construction industry (more drinking money for the lads Hegarty!)” appearing in the paper.”

“Another time I sent over a caption from Sligo. I couldn’t make out my handwriting so I went left to right: ‘John Murphy, Mary Murphy, and the baldy little fella with the glasses!’ I knew that by the time the thing arrived in Ballina I would have found out the name of the guy and fixed it. But of course, I was busy and Laura happened to be on duty so the caption of the photograph on the front page included the ‘badly little fella with the glasses!’ It wasn’t good... my only defence was he was a badly little fella with glasses!”

His time in the imbued him with a tremendous work ethic and gratitude for the heights he scaled in his career.

“This was the late '70s, we were in recessionary times. There was a magic when you got paid every week because you weren’t sure if there was going to be another one. It was a real struggle. I went to work for RTÉ for 41 years after that and I never really got over the miracle of a cheque arriving every fortnight into your bank account. I knew how hard we worked in the just to stay afloat.”

Tommie was still in his early 20s when he was named managing editor of the .

“I became the boss in the place eventually. I startedout as Sligo reporter and then we had a Sligo edition. I was 22 or 23 when I became the . We had a staff of over 30, so to be in charge - not only of the editorial side of things but also the finances - was real pressure. Every job I had in journalism after that was relatively easy! It was a fantastic time and people trusted me. Ernie Caffrey became a lifelong friend and mentor. Cathal Duffy, the same, he was enormous craic and great fun.”

Tommie saw how the machinations of Government could be influenced from the West.

“I saw those guys in action. One of the things I remember from Duffy was Padraig Flynn, who was a young TD in Mayo when Haughey became Taoiseach. John Healy would have been very highly regarded in Dublin, he was the director of the paper as well. They were lobbying to get a job for Flynn in Government and he wasn’t included in Haughey’s first list. So Duffy got Healy to write to Haughey. Healy went to see Haughey who asked him to make the case for Flynn on paper. Padraig Flynn got the job, that was his first ministerial position. Duffy went to his grave convinced that in order to make way for Flynn, Charlie McCreevy got bounced and pushed aside. History will show that McCreevey became one of Haughey’s enemies and biggest critics. That little incident in Mayo involving Padraig Flynn probably had a deeper impact on politics and Haughey’s whole history.”

Tommie was 24 when the opportunity to join RTÉ arose.

“It was hard to keep things afloat in the and you felt the pressure on the young shoulders. You were doing the business side of things as much as the journalism side. The hardest thing to do was to leave behind the people. I can see them as clearly today as I did all those years ago. I felt bad leaving behind what was a struggling but still afloat newspaper.”

He was excited by the prospect of a career in broadcasting.

“I could see the power RTÉ had in the community and how it really was the national broadcasting service. I was intrigued by the power of the medium.

"The job was a dream job because it was the North-West. I was going to be the person in charge of putting stories from my home region onto the airwaves. It was a tempting challenge. I had the gold standard in the parish next door with my lifelong friend Jim Fahey.”

His time as RTE's Northwest correspondent also gave Tommy a glimpse into life in Northern Ireland while covering stories in Derry.

“That was a different ball game for me. Even though we grew up close to the border you didn’t really understand Northern Ireland until you went to live there. I had no idea of how the Troubles played out in people’s lives until I went to work in Derry. It is a world you don’t know about until you are living in it.”

But before going North of the border, Tommy spent 12 years in Brussels as RTÉ’s European correspondent. He credits the media-shy Fiann Fáil politician Ray MacSharry with helping him land the role in 1989.

“What helped me get it was MacSharry being from my own area. He was the Commissioner for Agriculture but was quite cautious in his dealings with the media. He was in a really important portfolio and some of the managers in RTÉ thought I might be able to get the inside track on some stories that were really important for Ireland.

“They were fascinating times. It was the time of the fall of the Berlin Wall and so many things were happening in Europe. My job was to try and make Europe understandable to the people I grew up with and try and make Europe relevant to their lives,” explains Tommie.

One of his media colleagues at the time was a young English journalist named Boris Johnson.

“Boris was working there with the at the time. He was always humorous. He was starting his love affair with the Eurosceptics and was becoming their champion.

“There was a man called John Palmer, Brussels editor of , born in London but whose mother was from Tipperary. He was very pro-Europe and I remember him saying, ‘Watch that fecker, someday he will become Prime Minister.’ And nobody believed him.”

In 2001, the position of RTE's Northern Ireland Editor lured Tommy back home.

“I had always kept in touch with what was happening and was keen to see how the Republican movement with the armalite in one hand and the ballot box in the other was going to play out. I came back with great enthusiasm to see how the Peace Process was going to develop.”

During his early days in journalism and his time in the North, Tommy saw the devastation caused by paramilitary violence.

“The taking of life always represents failure. I was in the at the time of the explosion in Mullaghmore,” Tommy recalls.

In 1979, the IRA planted a bomb on Lord Louis Mountbatten’s fishing boat, Shadow V, nd then detonated it by remote control. The blast killed Mountbatten, 79, along with his grandson Nicholas Knatchbull, 14, a boat boy named Paul Maxwell, 15, and Lady Doreen Brabourne, 83.

“I saw them carrying in the bodies at McHugh’s Hotel in Mullaghmore where they used the headboards as stretchers and the sheets as bandages. I saw that and was in Derry at the time of the Hunger Strikes. I was in Ballykelly at the time of the Ballykelly bombing. I saw how that affected people.

“When you see the aftermath and you talk to the victims of violence, Michael Gallagher whose son was killed in Omagh, or Alan Black, who the one person who survived the Kingsmill massacre. You see how it just wrecks people’s lives.”

Tommie watched the Peace Process in Northern Ireland unfold before his eyes and believes the dark days of ‘guerilla warfare’ are over.

“I sometimes think we are starting to take the miracle of the Peace Process for granted. Okay, Stormont is closed and okay, they are fighting. But we transferred a lot of the anger from the streets and the viciousness and put it into a place called Stormont and let them have their rows and dysfunction there. But the killing has actually stopped and I don’t see it happening again.

“It’s such a relief to think it's over. You will see arguments about a United Ireland and people feeling they have been betrayed or left behind. But in my lifetime I don’t think we will see violence on the island or Ireland again which is a miracle.

Tommie will forever be associated with one of Ireland’s biggest-ever sporting stories – Roy Keane’s dramatic exit from the 2002 World Cup squad. His famous interview with Keane brought Ireland to a standstill.

“It was an important story. It was great to get it. My views on it haven’t changed over the years. I think it was a tragedy that he didn’t go back. There were mistakes on every side. I will never have any doubt that Keane was special and exceptional. I think it was too far gone by the time he returned home. Any sane person will say Ireland would be a better team with Keane as their captain and midfielder. End of story.”

He has enjoyed seeing Keane flourish as a football pundit.

"I’m really happy for him because he is almost as good as a pundit as he was a player. He is box office on television. I don’t think he will ever be successful as a manager because of the kind of instincts he has a player and the competitive side to him you can’t pass on those skills as a manager. They are playing skills not manager skills.”

Tommie has lived with cancer for 28 years since first he was diagnosed in 1994 with a rare form of the disease, neuro-endochrine tumours (NETs).

“I know lots of people in the West and in Mayo who have the same disease and we talk to each other and we support each other."

He helped found a support group for sufferers of the disease which celebrates its 10th anniversary this year.

“We have a wonderful co-operative. It’s a bit like a meitheal, with the HSE and the Centre of Excellence in St Vincent’s in Dublin. That’s something that I have worked with others to establish and try to improve. For people like me with a disease like that, that’s part of what keeps us going, that we are managing to improve things for people in the future."

The broadcaster has developed an incredible sense of his own mortality.

“Anybody who gets a diagnosis like that will you tell you that the worst few moments are when you are coming to terms with your mortality. But it can very liberating after that because you come to terms with the truth, that we all know in our bones. That we are just passing through and it’s going to end for us all someday. Once you know that, and you raise that, then every day you try and do the best you can. That’s where the title of the book comes from, ‘Never Better'.

"Every day I wake up, and say ‘God, I’m still here', that’s another bonus. I found I have no fear of pain or dying because I feel really, really lucky in my own case. When I was diagnosed in 1994, if I had died six months later, I would have had no notion of who Tommy Gorman was. I have two children, a son of 26, a daughter of 29, I have seen them grow up. I have had a wonderful life. The awareness of your mortality puts a whole lot of things you see in life into perspective. You say, ‘What about it? Never mind, isn’t it good to be alive'.”