When the world’s greatest trophy received the respect it deserved

West Ham and England captain, Bobby Moore, carrying a giant inflatable hammer after West Ham United won the FA Cup on May 2, 1964 beating Preston North End 3-2. Picture: Kent Gavin/Keystone/Getty Images

Young boys playing down at the Factory on a rock strewn pitch beside Blacksod Lighthouse. Piled jackets and no referee for the bunch who darted fish-like back and over and up down the pitch. Frees only called when both sides agreed, all done in a time that would put present day VAR to shame. Nobody keeping time but all in tune. It was May 2, the 1964 FA Cup Final, kick off at 3pm and all watching it in Mrs Sweeney’s living room in said lighthouse, eyes glued to the black and white TV that only arrived in the village maybe a year earlier.

West Ham United versus Preston North End were the teams. Boys being boys, we picked sides even though it was our first time seeing either. I plumped for Preston NE purely on the basis of Alan Kelly being the only Irish man on the field. However, my eye was drawn to a blond-haired captain, Bobby Moore, never blessed with pace but brains and timing to burn. A cracking match, 3-2 to WHU, a young Howard Kendall, only 17, in midfield for Preston. Something magic about West Ham though, the names rattled off in Bs, with Bond, Burkett, Bovington, Brown, Brabrook, Boyce and Byrne. Seven in all.

A year later West Ham went on to win the European Cup Winners Cup at Wembley, with Moore completing his captain’s trilogy in the same stadium in 1966 as he raised the World Cup for England. That was 60 years ago. Wow, where did that time go?

That first 1964 cup final planted something in all the young lads who watched it. Without bragging, we all went on to play the game at a comfortable level and all retained an interest up to… well, only they can say if they ever lost interest.

By the time the 1965 FA final took place, the Cuffe household had gone up in the world, we now had a television, black and white and its addictive lure posed my young brain a question. Would I go out and ever play in the evenings again?

Back then RTÉ only started broadcasting at 5pm. Outside the sun still shone and if it didn’t, our natural instinct won the day, we still played until called home.

The ’65 final saw a team with the first letter L win it for the first time.

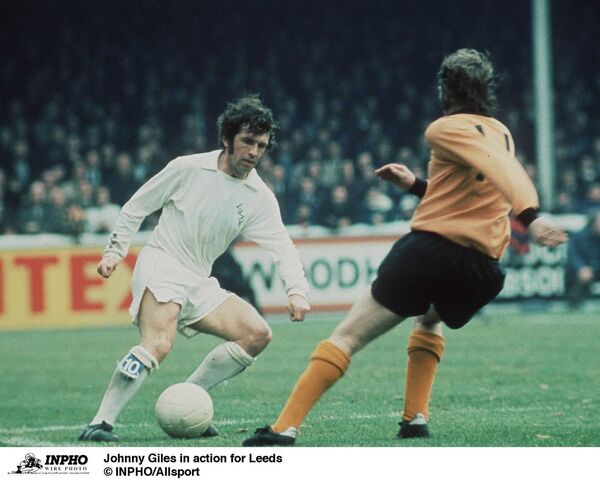

Liverpool was stretching its horizons and the cult of the Boot Room and Shankly was born. Leeds, for a decade to come, would also go neck and neck with them under Don Revie. Once more the Paddy in me came out as I wanted the win for John Giles but it wasn’t to be. And once more I went away with a new hero to dream about, Ian St John. Maybe it was the name, maybe it was because his socks-around-the-ankle late winner showed the never say die spirit that winners need.

By 1966 I was in St Muredach’s. I’m not sure why but I eschewed that final, Everton v Sheffield Wednesday, to play a small 4-a-side behind the goals on the top pitch in the college. Why? Probably peed off being confined in class and study most of the rest of the week, including having to attend class until 1pm on a Saturday back then. I missed a cracker. How the tables have turned. When Spurs beat a young Chelsea side managed by the mercurial Tommy Docherty in 1967, Tottenham were the kings, a Top Three outfit, and Chelsea were deep in their shadow.

As in 1967, we watched the 1968 FA Cup final in the science lab sitting around the Bunsen burners, pipettes and rubber tubes with a stench of mild acid, the big boys on the classroom stools, us on our arses looking up at the small TV that was only rationed out on All-Ireland final day or when a Pope died or was crowned. A boring match where a Jeff Astle header saw WBA beat a fancied Everton with its Holy Trinity midfield of Ball, Kendall (yes that one) and Harvey. By 1969 we were allowed to watch the cup final in what was known as the Diocesan Library, a noble space off limits to us unless for a class or the, by then, more occasional night watching the telly i.e. the Eurovision or some liturgical festival.

The TV was perched high in the Diocesan Room, atop a bookcase. We, by now the older lads, grabbed the front seats and the rest squinted at the black and white flickering box upon high. Mercer’s Man City gave a master class in attacking football under the coaching skills of Malcolm Allison, great coach, not great manager as he would prove many times later. Flamboyant was Mal, successful was Mercer. Again the names run off the tongue, but I’ll settle here for Bell, Lee and Young. Almost a rock band.

The 1970 final has to the one most followers love to relate back to. Chelsea now under Dave Sexton had a beautiful team that could play football but if the occasion called, also kick. Their opponent was master of the darker arts, a great Leeds side. Unlucky Leeds played Chelsea off the bog that Wembley had formed into after the week earlier Horse Show. The pitch, heavily sanded, led to the Leeds keeper making one awful blunder. Somehow or other though, Chelsea clung on to Leeds like the muck stuck to the players.

The replay was a classic and played at Old Trafford midweek. Chelsea won and the Damned United, Leeds, missed out on a treble that season. By 1971, I was in Galway and colour tv was on stream. Arsenal beat long sleeved Liverpool on a boiling day to clench the double. A rare feat back then, a Middle Eastern backed expectation today. Galway again for a 1972 borefest where Leeds finally shed the bad luck vibe and beat a sour Arsenal – the highlight being Mick Jones marvellous cut back and Alan Clarke’s laser guided header low past Barnett of the Gunners.

I was in England in 1973 but not Wembley. I watched that final from the street in front of a shop window as Bob Stokoe led Sunderland to a giant killing act over, yes, Leeds again. However, by 1974 I was in The Mullet Bar in Belmullet on a high stool, cold pint in front of me, watching Bill Shankly’s Liverpool fillet Malcolm McDonald’s Newcastle in a masterclass. Almost a decade had passed since their last win and Shanks went out of Wembley a Liverpool God.

By 1975 I was on Inis Óir Lighthouse, two keepers for company as we watched an inevitable West Ham and Billy Bonds win over their former captain’s Fulham. Booby Moore, the king of Wembley, finally lost there. Working on lighthouses, it was the luck of the draw whether you were ashore or at sea for the finals. I was on Rockabill off Skerries when Southampton and Bobby Stokes claimed the 1976 final over Tommy Doc’s United. And the same Lighthouse a year later when United avenged ’76 and stopped Liverpool from a historic treble that season. A week later the Doc was sacked.

A change of career in 1978 saw me at home on a break watching in our own kitchen, our pet dog beside me, crisps, Coca Cola and a bar of Fruit and Nut on the table. Ipswich and Bobby Robson spoiled Arsenal’s O’Leary, Brady, Stapleton, Jennings, Rice and Nelson’s plus the island of Ireland’s day. The 1979 final saw me on duty and my boss, knowing I liked soccer, subtly placed me on a post that was furthest from the nearest television. Nice. But the Erris man in me seeped out. I timed my patrols to pass the telly at opportune times. Arsenal spoiled United’s day with a late winner and I spoiled the bosses with my perfectly timed runs. I got in all goals.

The 1980, ’81 and ’82 finals, won by West Ham and two in a row for Spurs, saw me off duty and in a pub. The advent of the exotic foreigner was announced in English football with the arrival of Ardilles and Villa to Spurs in 1981 only to be temporarily sidetracked by the Falklands war a season later. Leggy Manchester City winger Tommy Hutchinson scored for both sides in the ’81 final. The ’82 final would be Spurs’ highwater mark. Big Ron Atkinson revolutionised Manchester United in ’83 and though lucky to draw the first match against Brighton, the final of famous last words ‘and Brighton’s Smith must score’ gained particular relevance when Smith didn’t and Brighton lost the replay 4-0.

The boy of 1964, Howard Kendall managed Everton to the 1984 final win over Elton John’s Watford. I’m not sure where I watched it such was the forgone conclusion I had about the outcome. I’m not even sure I watched it at all. I was working on Spike Island for the 1985 final. I watched it with the 140 inmates we had on the island. Tense and tight was the match, a bit like my workplace that year. A thunderous tackle and sending off for Kevin Moran and a sublime curled left-footed winner from Norman Whiteside gave United a deserved victory.

By 1986 I was back in Dublin, engaged and flat out at work. Hard times workwise but made easier by an improbable Liverpool double, both achieved over city rivals Everton. The city of Liverpool rose from the ashes of the Heysel and its tragic outcomes to restore a smidgeon of sunlight on Merseyside. Dalglish made the transition from player to player-manager with success. I watched the 1987 final from the comfort of home. Glorious sunshine as Coventry won their maiden FA Cup. Spurs failed for the first time to win a final in a year ending in 7 or 1 that they competed in. They won trophies in 1901,’21, ’51, ’61, ’67, ’71 and ’81.

I was in the Lake District for the 1988 final when the artisans that Wimbledon were deservedly beat Liverpool. John Aldridge had a rare penalty miss. The cult of Vinny Jones and the Crazy Gang was cemented. Business as usual for Liverpool in 1989, another glorious day and my first born on my lap. Both Aldridge and Rush scored but as Liverpool are currently finding out regarding number 9s, two onto one doesn’t go. Aldo, a consummate striker, made way the following season to allow Rush rule.

It started with Liverpool for me and ended with them. Work, kids and life took over. The 1990 final was blur, as were the rest. Spurs got back on track winning the 1991 final and after that it’s a haze or highlights late at night. Around 2001 Manchester United opted to withdraw from the FA Cup in order to curry favour with FIFA and play in some meaningless tournament in January in order to get England the hosting of the next World Cup. They didn’t. An FA Cup won by Ferguson in 1990 that saved his career at United and launched him and his club into history, was consigned to the bin by big money.

A couple of weeks ago in America, Johnny Infantino managed the impossible. He out-Blattered Sepp Blatter in the World Cup draws. What was once the pursuit of the common man is now diced, sliced, monetised and fed back thorough a mincer to the gullible and greedy.

I was lucky. I managed to see little Bobby Collins of Leeds in the 1965 FA Cup final, old fashioned boots up to the ankles, laced around and under the boots, white socks that were made of wool and turning slightly yellow from the wash. The picture of the diminutive Collins, 5’3” shaking hands with fellow Scottish legend Ron Yeats aka The Colossus, standing 6’3” remains my abiding memory.

Simple times and respect for the world’s greatest trophy. A trophy considered worth less than a Top Four qualification for the Champions League by Arsenal’s Arséne Wenger, a tournament today bloated with meaningless matches and loud blaring music. As the Stanley Matthews Final of 1953 or the Brady Final of 1979, Bert Trautmann’s broken neck but playing on in the 1956 final or the Rocky Villa solo effort against Man City in ’81 remain in the memory of those of a certain age, heroes and tales were formed. Today it’s a vehicle for hedgefunds and shady states. Van Morrison’s song captures that past, the childish innocence and belief in sport, not money making.