We can learn a lot from this Lenten season

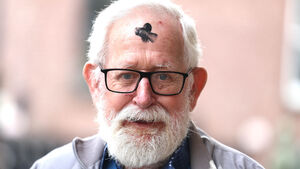

Greg Kennedy, from Co Laois, outside Mary's Pro-Cathedral in Dublin earlier this month with the traditional ash cross on his forehead, signifying the start of Lent. Picture: Leah Farrell/ RollingNews.ie

As February's pale light fades, the heralds of Lent have already roused the faithful from winter's lethargy. For nearly two millennia, these 40 days presaging Easter have summoned legions to repentance through ritual self-denial - be it ashes daubed on furrowed foreheads in sombre church rows, mouths stopped by fasting from favourite foods, or various acts of discomfort embraced to purify body and soul.

The very origins of Lent extend back to the formative years of the early church itself. As Christianity emerged from its initial persecuted minority status in the Roman empire to gradually become the dominant faith under Constantine by the 4th century AD, its newly mainstream adherents sought more profound ways to embody their saviour's passion through penitential preparation leading up to Easter celebrations, the very core of the faith commemorating Christ's death and resurrection.

Jerusalem communities had observed pre-Easter fasts since at least the 2nd century, but by 325 AD at the pivotal Council of Nicaea, a more organised Lenten season was officially formulated by bishops to span 40 days of committed fasting excluding Sundays leading up to Easter, echoing and memorialising Christ's own 40 days surviving in the barren Judaean desert on nothing but prayer and scripture to thwart Satan's sly temptations.

This etymology of the word "Lent" itself evokes the seasonal themes of death and reawakening - derived from old Germanic words for springtime, denoting the vernal equinox arriving midway through, even as wintry deprivation gives way to longer hours filled with birdsong and timid flowers scenting the once frozen air. Lent commences each late winter just as hints and promises of reborn light begin brightening the sullen horizon. The faithful enter into this liminal landscape between decay and green shoots, pushing determined through the thawed crust of the earth, accompanied by biblical texts of hardship suffered.

But why such emphasis on what seems like voluntary misery? The goal of alignment with Jesus' tribulation has always carried deeper motivation - believers traditionally focused on prayer and penitential sacrifice throughout Lent to spiritually purify themselves to become worthier, more humble vessels receptive to commemorating the promise of Easter's promise. The believer empties the soul's cup to make space for an infusion of grace by laying aside earthly distractions and appetites for a season.

Given human nature's penchant for excess, pious intentions sometimes morphed into competitive zeal for outlandish acts of self-denial among medieval ascetics and mystics seeking to outdo each other in conspicuous displays of virtue. Hermits headed to unforgiving deserts dragging millstone collars, solitary caves, and pillar tops, which become bizarre occasions for determined spiritual athletes abandoning all creature comforts to embrace naked suffering.

Some undoubtedly mistook sheer extremity for sanctity, like fifth-century St Simeon perching atop a stone column outdoors in Syria for over 35 years, or the aptly named hermit St Alipius 'The Obedient' who slept 90 nights in a thorn bush to spiritually toughen up on the advice of his elders! Other cautionary tales warn against excess, like the possibly apocryphal 15th-century Belgian native Wilgefortis, who prayed desperately during Lent one year to lose her lovely looks, which kept suitors pestering her like flies to honey. Awaking the following day to find her prayers answered with an enviably lush beard sprouting on her cheeks was perhaps divine aid taken too literally! Though in fairness, this effectively quashed all marriage prospects.

At the opposite extreme, throughout Catholic Europe's Middle Ages, the freewheeling season of carnivals arose leading right up to Lent's monastic starkness - a final outlet for hedonistic feasting and carousing before ashen privations of fasts and gloom. Riotous celebrations still mark places today with costumed parades, dancing and surfeits of foods expressly forbidden once Lent begins the next dawn.

Profane costumes, revelry and flaming braziers echoing pagan practices unfold and gorge the senses on worldly delights soon to lay fallow and hidden for 40 days of physical and spiritual housekeeping. One last collectively sanctioned bacchanalia before the faithful reluctantly surrender earthly things to walk through Lenten wilderness stripped bare of all but the necessary.

We moderns may fail to see the intense commitment behind medieval Lenten rituals. But we can still learn from our ancestors in practice. Their extreme fasts and other forms of self-denial served social purposes, too, as winter food supplies dwindled. Abstaining from rich foods for six weeks conserved dwindling supplies and already bare larders.

Not subject to constant distraction, their eyes stayed focused on eternal truths and the condition of their souls, less worried about the quality of their earthly lifespans like we are today. Though time flows evenly through all eras, we have become obsessed with business and financial concerns; observing Lent allows the gaze to turn inward and upwards.

If we quiet our rushed pacing to align with the natural cycles of this world, insights might still emerge on why generations past bothered to sanctify certain seasons as sacred. We can observe them arraying weeks as varying lenses to peer through - the uninhibited revels of Carnival giving way to Lent's stark stillness and focus on things eternal, not worldly. Attuning ourselves to these rhythms may realign our vision as well.

Do we make good use of this time-honoured ritual dance again this Lent? The logic seems bizarre yet oddly familiar when etched against nature's cycles that our ever-full calendars cannot erase or comprehend. Setting productivity aside, what cleansing might come from plunging into deeper waters of mystery and meaning? Not seeking to control time in measured increments but to be transformed by it through realising it stretches into the infinite.

Forty days of the desert are already well underway, where paths to self-knowledge still cut through for those embracing the season of thrift with renewed understanding. Can we, the most media and entertainment-saturated generation in history, enter into this adventurous hope again, emboldened like past pilgrims by glimpsed traces of stillness and peace amidst the blizzard of digital stimulation? Listen closely for whispers of a hidden quietude stirring those unfamiliar spaces, signalling that the divine still walks nearby, longing to lift us from incessant distraction into intimate belonging.

Though the world may scoff and science dismiss the Lenten spring cleaning of ages, our open minds can perceive the mystical even amid chaos. We can prepare inner sanctuaries for a much-needed peace to breach hardened divisions between matter and spirit, reclaiming our inner lives as a spiritual dominion once again.

Stepping back from the hectic pace of life for self-examination and simplification, even briefly, can offer much-needed perspective and peace. Taking time to declutter physical and mental spaces creates room for what matters to flourish again. By letting go of excess media stimulation, overthinking and self-judgment, we reclaim agency over our lives and reconnect with our innate wholeness.

The Lenten season reminds us that endings and loss make space for new beginnings and freedom. Like the natural cycles of our planet, dying leaves in autumn give rise to fresh green shoots in spring. Past wisdom can illuminate our way forward as we pause to reflect on this Lenten season. Stop, be still, and listen; you might glimpse the eternal in a simple birdsong. It might be the beginning of a beautiful and lasting relationship with an estranged self.