The enduring appeal of the horror movie

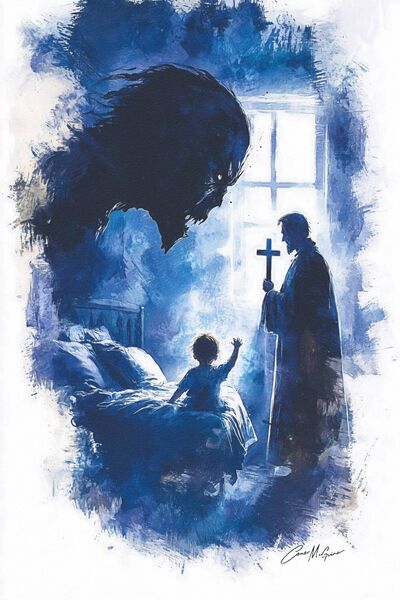

A still from 'The Exorcist', which was one of the most controversial movies of the 1970s.

There's a perverse pleasure in being terrified. We huddle in darkened cinemas, stuffing our gaping gobs with popcorn as our primal fears are prodded and our nerves frayed. The horror genre persists in its unholy mission to unsettle us with our tacit permission, each new release promising freshly-minted nightmares. But why, disturbed and discomfited, do we keep returning for more?

We might label it catharsis - a safe way to process our deepest anxieties about death, the unknown, and the monsters that may lurk under our beds and in our psyches. Or maybe it's simple voyeurism - a chance to peer into the abyss of horrors without actually leaping in. Whatever draws us to the ritualised scare, its roots run deep in the human experience.

From Irish myths of vengeful fairies to Victorian penny dreadfuls, we all enjoy a good scare. But the silver screen truly unleashed horror's visceral power when silent classics like gave moving form to our nocturnal terrors. Later, Universal's pantheon of pantomiming monsters - Dracula, Frankenstein, and the Wolf Man - became cultural touchstones.

The 1970s ushered in a new era of psychological horror when traumatised a generation with its stark depiction of demonic possession. Suddenly, the terror wasn't confined to some remote gothic castle but laid claim to new domestic rights in the innocent vessel of a young girl. It was a paradigm shift that still reverberated over the decades to the genre today.

This brings us to , Hollywood's latest attempt to cash in on our appetite for theatrical spiritual warfare. Russell Crowe, looking unrecognisably haggard, plays a washed-up actor in a film about, you guessed it, demonic possession. Art allows art to imitate life as Crowe's character grapples with his own inner demons of addiction, failure, and trauma. And sadly, Crowe is a miscast within a miscast; his declining muscularity is so at odds with the embodiment of any cleric I've ever known, slight or portly of build. Equally miscast is effete David Hyde Pierce as the troubled priest, who once possessed, is more reminiscent of a fatally constipated octogenarian than an agent of the devil.

The concept is clever, tapping into the longstanding myth of "cursed" horror productions. From infamous on-set accidents to the tragic deaths surrounding , there's a rich vein of lore about the perils of summoning the demonic into cinematic darkness. shamelessly mines this territory, blurring the lines between the fiction industry and reality in a way that should, in theory, heighten the sense of creeping terror.

Crowe is no stranger to complex, troubled characters, and he brings a gravitas to the role that elevates what could easily become hackneyed material. His portrayal of an actor confronting personal demons while literally battling fictional ones offers the potential for a revelatory exploration of addiction, trauma, and the merciless grinding of vulnerable stars by the entertainment industry. It's a shame that the film never quite capitalises on this topical premise.

Despite some atmospheric touches and Crowe's committed performance, never transcends its B-movie and stock horror trappings. The third act descends into a cacophony of screaming and gratuitous stabbing, any nuance lost in the maelstrom of bloodied scenery. It's as if the filmmakers, having set up an intriguing premise, were unconvinced by their fanciful ruse and lost faith in their ability to sustain it and reverted to horror genre clichés.

This reliance on tired and predictable storylines is symptomatic of a broader issue in contemporary horror. We're inundated with formulaic retreads, terrorised by familiar plotlines more than inventive horror stories. Most notable among these is the once groundbreaking franchise, which has devolved into a parody of itself. Even attempts to reinvigorate classic properties often fall flat, relying on insipid nostalgia and jump scares rather than genuine innovation.

Yet despite these present shortcomings, horror endures. There's even something oddly comforting about these formulaic exorcism flicks. We know the plotline - the initial scepticism, the escalating phenomena, the climactic battle of good versus evil, and the inevitable fatalities. It's cinematic comfort food for the morbidly fascinated, present company included.

Perhaps that's the true appeal of horror - not the orchestrated moments of terror but the familiar shared rituals. We gather in the dark, submit ourselves to fear, and emerge at least physically unscathed. For a few hours, our quotidian anxieties are subsumed by more elemental terrors, and we face the dark void of our revealed subconscious and live to tell the tale.

This ritualistic aspect of horror viewing speaks to a more profound human need. In a world of ever-present, amorphous threats and real threats - climate change, economic instability, pandemics and escalating wars - there's a certain relief in confronting a momentarily tangible, if fictional, monster. The demon can be exorcised, the killer ceremoniously unmasked, and the malevolent curse lifted. It's a temporary respite, shoring up our hope from the genuine horrors that continually haunt our daily lives.

The best of the horror genre allows us to explore taboo subjects and confront societal fears in a safe, socially acceptable format. An accomplished horror film isn't just about scares – it can be a mirror held up to society, reflecting our collective anxieties and shortcomings. The early George A. Romero zombie films tackled consumerism and racial tensions, and more recently, films like and have used the genre to examine racial inequality and the lingering legacy of slavery.

, for all its flaws, tries to grapple with this tradition by focusing on an actor struggling with addiction and past trauma; it nods towards the continuing horrors of substance abuse and childhood exploitation. The film-within-a-film structure shines an unflattering light on the entertainment industry's sometimes parasitic relationship with human suffering. These are weighty but relevant themes, even if the execution falls abysmally short, as in this case.

It's worth noting that horror, perhaps more than any other genre, because of its predictability, is subject to the law of diminishing returns. What terrified audiences into abandoning their seats a decade ago may elicit little more than a yawn today. This constant need for novelty drives imaginative innovation but also leads to alarmingly extreme content. The 'torture porn' subgenre of the early 2000s, unthinkable as mainstream a decade earlier, exemplified by films like and the later entries, pushed the boundaries of on-screen violence to a point where many viewers, as I did, simply checked out.

In a creative response, we've seen a rise in what's often termed 'elevated horror' - films that prioritise atmosphere and psychological dread over gore and jump scares. Films like and have garnered critical acclaim for their artful and minimalist approach to terror. These films often employ grotesque subliminal suggestion and imagination, using unsettling imagery and themes to hint at a deeper, lingering malaise in the banal and ordinary.

, stuck in this time and place, is caught between these two approaches, never fully committing to either. It's too self-aware to offer flights of horror and become grounded as a straightforward exorcism film, yet lacks the artistic gravitas to transcend the weight of predictability.

Yet even in its failings, speaks to horror's enduring appeal. As long as things bump in the night, the cinema-loving public will keep lining up to be scared. It's a peculiar compulsion - to seek out what unsettles us. In doing so, we confront our latent fears and emerge, if not stronger, at least reminded that we're still alive. I'm scared, therefore, I am.