The arrival of the telephone in rural Ireland

The poles and copper wires of the telephone service once heralded huge progress in rural Ireland. Picture: Pat McCarrick

There was a time when very few people had the telephone in their home. The priest, the doctor and maybe the local shop were the usual clients. At that time, in the Ox Mountain region, if you wanted to make a call, you went to the local Post Office. If you were lucky, there might be a phone kiosk outside; if not, the whole world knew your business.

In the early 1970s, lines of poles, strung with copper wires, began to appear along the road that I walked to school. The Department of Posts and Telegraphs were in full swing, laying out a new telephone infrastructure and even at that, not every house could afford to avail of the service.

Following the invention of the telephone by Alexander Graham Bell in Boston in March 1876, one might assume that his invention would immediately capture the attention of the American public. This was not the case, however, and many people felt that his new ‘speaking telegraph’ would never achieve commercial success. Even the US President at the time, Rutherford B. Hayes, reportedly said, “That’s an amazing invention, Mr Bell… but who would ever want to use it?”

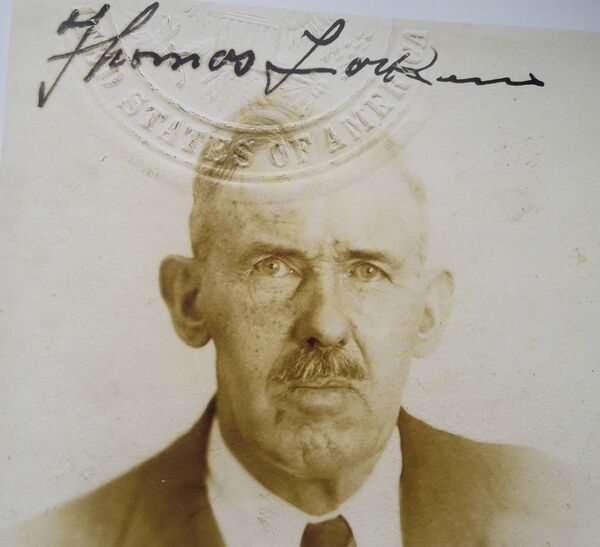

I was delighted to receive a prompt in recent weeks to feature the birth and growth of the telephone. The reminder came from Michael Larkin and from his own personal interest in the telephone, its history and the people behind its growth. Michael was telling me about an ancestor of his, Thomas Larkin (1874-1953), who emigrated to America and later became one of the early telephone pioneers with the Bell Telephone Company of Pennsylvania.

According to Michael’s research, in his book, , his ancestor was part of an unfolding story, part of telephone history.

Thomas Larkin was born in the townland of Derrew, close to the village of Ballyheane, near Castlebar in Co Mayo. While he was just one of several thousands of other young Irishmen and women who made that perilous voyage across the Atlantic ocean to America, his story, together with its interwoven themes relating to immigration, transatlantic connectivity and evolution of telecommunications, became a fitting symbol of transatlantic connectivity between Ireland and the United States of America.

At the time of Larkin’s arrival in Philadelphia there were reputedly endless work opportunities available, but such opportunities were off-set by the number of immigrants arriving daily in the city. Larkin stated years later: “If I had the fare to return to Liverpool at the time I would have done so.”

However, huge advertisements were visible throughout Philadelphia, promising more opportunities further west. So, Thomas, following his instincts, headed west and eventually secured employment with the Bell Telephone Company of Pennsylvania. It was with this company, in the city of Pittsburgh, that he spent most of his distinguished career. With great pride and with a strong work ethic, he accompanied the telephone on its rise to eventual stardom.

While his yearning to return to the land of his birth was fulfilled following his retirement, Thomas seriously contemplated returning to Pennsylvania once again as the Ireland he returned to in the 1930s was still decades behind America in terms of economic progress, infrastructure and communications. Michael Larkin goes on to describe his ancestor’s legacy and the tangible reminders of his career in America.

Returning to my own early telephone experiences, it seems the only calls made then were to the doctor, the vet or the local AI office. These calls were made in an ascending order of frequency; the doctor - not so often, the vet - a little more often and the AI office - a weekly occurrence, especially in the early months of summer. For the uninitiated, AI in this instance stands for Artificial Insemination (of the bovine kind).

There were two places for making such calls in our locality; the Post Office and the local Bed & Breakfast. The round trip to the Post Office was over four miles and the round trip to the B&B was over two miles. That’s a long way for eight-year-old legs. So, the first prerequisite of being sent to call the AI was to be able to cycle – otherwise the poor cow could be gone off heat and the whole thrust of the farming year would be thrown off by several weeks!

The routine at the Post Office was that you simply informed the Post Mistress of your business and she made the call. The call usually went like this: “Is that Tubbercurry 48? I have a call for Harry McCarrick, Cloonbaniff, noticed early this morning… yes, and a black bull please.”

Making the call at the local B&B was a different kettle of fish. The B&B belonged to an enterprising local woman who extended her cottage so that each summer she could make a small income from accommodating German fishermen, who at that time loved nothing better than fishing the loughs and rivers of the Ox Mountains. In the early days, all her bookings came by post but when the poles and copper wire appeared, she was one of the first to have a phone installed. Clever woman that she was, her phone took the form of a coin box operation; one of those button A and button B jobs. As well as making sure she always had the funds to pay her phone bill, it meant that the phone, positioned in her hallway, was also available to her neighbours. One simply waltzed in her front door, made their call and often left again without ever seeing the woman of the house.

We have come a long way since Thomas Larkin took up employment with the Bell Telephone Company in Pittsburgh. Gone are the cumbersome devices that once made history. Today, as I walk the same road I once walked to school, the poles and copper wire that once heralded great progress, are falling into decay. They have been replaced with a new communication fabric of giant telecommunication masts, radio waves and fibre, and thanks to the thousands of satellites that float overhead in outer space, I have a phone in my pocket.

Michael Larkins book, , is available in local bookshops and from mayobooks.ie.