Ravens carry myths and legends on their wings

Pictured at the launch of the Boyne Valley Viking Experience 2024 was Shay Cullen in Viking dress with a raven on his leather-clad arm. Picture: John Sheridan

In the genteel world of garden bird-feeding, where tits flit, and robins boldly go, there's always one who refuses to play by the rules. Enter stage left, with a swagger that would make Donald Trump nod in approval, our feathered anti-hero: the raven. Or is it a hooded crow? At this distance, one can never be entirely sure but frankly, it hardly matters.

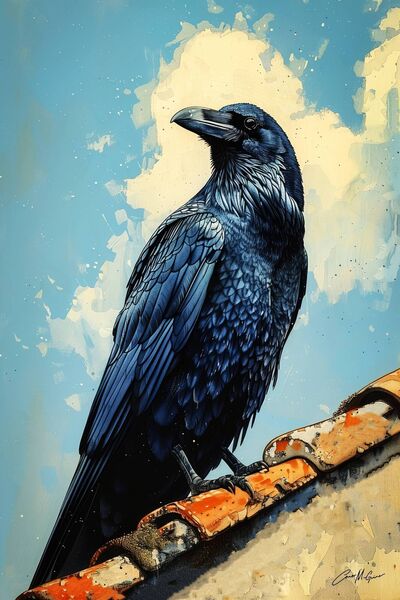

There he perches, this avian Lucifer, on the neighbour's rooftop – a crack of black on blue, as if the very sky had split open to reveal the darkness beyond. One can almost hear the collective intake of breath from the smaller birds, their tiny hearts aflutter with a terror as old as time itself. For this is no mere bird; this is the emissary of the dark arts, the shoulder companion of witches, a feathered phantasm that has spooked our collective unconscious since we first huddled around fires in primitive dwellings, telling tales to keep the night at bay.

Our corvid friend – for that is what he is, regardless of the specific branch of his family tree – is here for a far more prosaic reason than to terrorise the local birdlife or portend my impending doom. He's here for the bread, the domestically mundane routine of opportunistic foraging.

As he swoops down in a flurry of feathers, I cannot help but be reminded of Milton's fallen angel, descending from the heavens with terrible grace. But instead of tempting Eve or battling the forces of good, our feathered Mephistopheles is content to pilfer a few crusts left out for more socially acceptable avian diners.

But I can't judge too harshly, as I've eaten my fill from the cupboard. After all, is this not the very essence of survival? Red in tooth and claw, as Tennyson so aptly put it. And yet, for all its jagged outlines and stilted manners, there's something almost endearing about this dark interloper, with his beady eyes and proprietary air. He's an outsider, a creature that treats our human world with cunning contempt.

It's no wonder that ravens and their cackling kin have captured our imaginations for millennia. From the earliest Norse myths, where Odin's ravens Huginn and Muninn (thought and memory, respectively) flew across the world to bring him news, to the Celtic goddess Morrigan, often depicted in crow form, these birds have been our constant companions in the realms of myth and legend.

But it is perhaps in literature that our dark-feathered friends have truly spread their wings. Who could forget the raven in Edgar Allan Poe's eponymous poem, that grim, ungainly, ghastly, gaunt, and ominous bird of yore? Perched upon the bust of Pallas, just above the chamber door, croaking 'Nevermore' with all the finality of the grave itself. It's enough to give Jacob Rees Mogg a fit of Victorian vapours.

And yet, for all their gothic associations, ravens and crows have also been seen as tricksters, wise counsellors, and even creators in various mythologies. In many Native American traditions, the raven is credited with stealing the sun and bringing light to the world. My garden interloper might fancy himself a similar hero, liberating bread from the dizzy tyranny of smaller birds.

In the realm of science, ravens continue to astonish and confound researchers. In 2017, scientists at Lund University in Sweden discovered that ravens can plan for the future – a cognitive ability previously thought to be unique to humans and great apes. The ravens in the study learned to use a tool to open a puzzle box containing a treat and could select the correct tool from a range of objects when offered the chance to do so 17 hours later. This remarkable intelligence and adaptability of these birds is truly fascinating.

I observe my companion strutting across the terra firma, still suspicious and alert. His wariness is almost comical, as if he half expects the door to swing open and this human to seize him. It's a reminder that for all their mythic grandeur, these are still very much creatures of flesh and feather, driven by the same wariness as their smaller cousins.

And yet, as he pauses to eye his reflection in the glass door, I can't help but wonder what goes on behind those obsidian eyes. Ravens and crows are among the most intelligent of birds, capable of problem-solving, tool use, and even recognising human faces. They have been observed holding 'funerals' for their dead and fashioning hooks from wire to fish food out of containers.

Recent studies have shown that some corvids possess cognitive abilities on par with great apes. But for all their intelligence and adaptability, ravens and crows have not always fared well in their interactions with humans. They have been persecuted as pests or harbingers of ill fortune in many parts of the world. The collective noun for ravens - an "unkindness" - speaks volumes about our historical relationship with these birds.

Yet despite these challenges, they persist and thrive, occupying the upper branches of trees that brush the skies on our urban peripheries. From the Tower of London, where legend has it that the kingdom will fall should the ravens ever leave, to the streets of Tokyo, where crows have been observed using traffic lights to crack nuts, these birds are very much a part of our modern world.

But the most intriguing recent development in raven lore comes from the world of artificial intelligence. In 2018, researchers at the University of Washington used machine learning algorithms to translate ravens' calls, discovering that these birds have a complex system of communication. They found distinct calls for different situations, including warnings about predators and expressions of anger or happiness.

Which brings us back to my garden interloper, now contentedly feasting on his ill-gotten gains. There's something almost regal about him, a sense of entitlement that would shame the most blue-blooded aristocrat. And why not? For all our myths and legends, fears and superstitions, he is, in the end, just a bird doing what birds do best – foraging.

As he retakes his wings, a flurry of darkness against the blue sky, I feel a sense of admiration. For in this most ordinary of acts - the theft of a few breadcrumbs - we see echoes of all the mystery and majesty that has captivated us for millennia.

From the lofty heights of divine messenger to the disgrace of plague harbinger, from trickster god to backyard bread thief, the raven has played many roles in our collective imagination. And through it all, they've watched us with those beady, intelligent eyes, perhaps wondering towards what end all our frenetic, self-important activities are purposed.

So the next time you see a raven or crow in your garden, spare a thought for the rich tapestry of myth and legend they carry on their wings. And if you're feeling generous, leave out an extra crust or two. After all, who can deny a creature that has inspired everything from ancient gods to Edgar Allan Poe?