My long, difficult road back to the Church

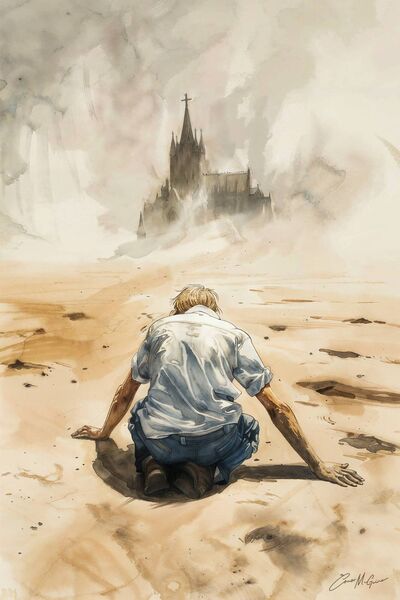

The Church is like a beacon in a vast desert. Illustration: Conor McGuire

They say the road to hell is paved with good intentions, but for me, the road back to Rome was cobbled with missteps, wrong turns, and detours into every cul-de-sac of modern secularism and temptation. Like one of Chesterton's wise and jocular elephants, I meandered circuitously through acres of empiricism, humanism, and every other "ism" the 20th century hurled at the Church, only to find myself, battered and bewildered, right back at the door of the Faith.

My tepid Catholicism wasn't for want of trying the alternatives. I was the most diligent of apostates, immersing myself in every spiritual dead-end I could find.

But nothing, absolutely nothing, could fill the God-shaped hole at the centre of my being. The more fervently I embraced the tenets of godlessness, the more that celestial spark within me guttered and waned.

It took a profound awakening, which I'll leave to your prurient imagination, to stop me in my tracks and force me to reevaluate. As I reassessed the sources of a battered ego, I finally understood, with a soul-shaking clarity, that I had been chasing distractions, constructing endless to-do lists of diverting but meaningless distractions when the answer was staring me in the face.

Like the Prodigal Son, I had embezzled my spiritual inheritance and fled to the far country, frittering it away on ephemeral trifles. But the Church was there all along, patiently waiting with open arms and the spiritual sustenance my depleted soul craved.

As Chesterton wrote, the Catholic Church is the blunt "other answer to...the summons of life". It satisfies that universal human intuition -hardwired into us by our Maker - that there is more to this existence than the mundane and material, a calling to transcendence that echoes in every heart.

All my philosophical and personal wanderings were just crude, stumbling attempts to apprehend and commune with the divine. But as the Church teaches, we are made for metaphysical realities; no counterfeit will do. St Augustine wrote in his Confessions, "Thou hast made us for Thyself, O Lord, and our heart is restless until it finds its rest in Thee."

It's a lesson that some high-profile artists never seem to learn. From the rage of heavy metal to the cooing pop seductions of an ageing Madonna, they keep recycling the same tired anti-religious provocations: a crude misuse of a crucifix here, a jarringly blasphemous image there, lobbing esoteric rhetorical grenades at a scorned faith.

Yet for all their conceptual contortions, for all their taboo-baiting and publicity-stunting, they're just charlatans butchering the most extraordinary artistic subject imaginable. Their cynical and shallow forays into mock spirituality are mere dress-up games next to the Church's profundities.

To adapt a phrase, the Church is the imperishable icon minted in the emergency of uncreated grace. It is the safehouse of mystery, the bulwark of the miraculous in our world hollowed out by materialism and scientism. Its teachings illuminate the most profound puzzles of existence: why there is something rather than nothing, the nature of being and consciousness, how to live a meaningful life, and the ultimate questions of morality, truth, and immorality.

No amount of pop-Buddhism or Gnostic chic could slake the thirst the Church's treasury of metaphysical wisdom reawakened in me. Not when the Faith holds the unfathomable keys, the staggering truth of the Incarnation, the shock of the Resurrection.

As Flannery O'Connor wrote, "I was born to be a Catholic, and the Life You Gave Me has been shaped by it whether I liked it or not...Holy Church included."

So I stand again in the courtyard of the Church, a prodigal penitent, gifted with the constancy only age can bestow, ready to bend the knee and resubmit to familiar disciplines - to the pious rigour of Her moral philosophy, the rhythms of Her liturgical year, the splendid poetry of Her rites and devotions.

Of course, my return to the Church has not been without its struggles and stumbles. I wish I could say that my philosophical repatriation was a seamless, secured landing - that I transitioned gracefully from heretic to celebrant without undue turbulence. But that would be a lie, and dishonesty ill-becomes a hopeful spiritual awakening.

If I'm to fully inhabit the repentant writer's persona, I must own up to my continued failings, my personal and spiritual pockmarks that make a mockery of the piety to which I aspire. Despite repeated efforts, I am still burdened with the inbred weakness that led me so far astray in the first place.

My failings now aren't the excesses of my misspent youth but the more pedestrian vices of middle age - the beige trespasses of complacency, satisfaction, pride, and the rest of the deadly litter. I still find myself lapsing into spiritual indifference, ingratitude, and bouts of unexpected cynicism about the Church's flawed and sordid underbelly.

And when those moments of desolation descend, it can almost be clarifying - in the worst way. The dark doubts and scepticisms come flooding back: Perhaps I was right the first time in skirting the Church's perimeters with caution. Her impossible moral demands, her scandals and hypocrisies, her arcane mysteries... why am I lashing myself again to this wounded ship of antique superstition?

It's then that I'm forced to remember the great exemplars of sinner-saints who preceded me: Augustine himself, the Platonist turned Pauline-shocking convert; the scandalous Moses the Black; Mary of Egypt, who went from satirised trollop to eremitic astonishment; the Apostle Paul who helped murder Christians before being slain himself for the Faith.

Their witness is a perennial reminder that the Church is not a museum for the saintly but a sin-sick man's wayside hospice - a source of spiritual triage, an aid station for dressing the gashes of transgression and failure that all men accumulate on their journey. Her halls are choked with riff-raff, not plaster perfections.

Which is what has made Her sustainability so miraculous over the centuries. That She has survived and even flourished despite all the scoundrels and reprobates passing through Her doors is a testament to Her teachings' rough vitality and adaptive resilience, a bulwark of sanity in an insane world.

I may falter and fail again and again in the scuffling mêlée of daily life, but that Eucharistic anchor, extended to even the most undone, will see me homeward. And on the days the waters of doubt seem too dark and frothing to pass, I'll cling all the tighter to the Church's vessel and let grace's unseen hand steer me, battered but unbroken, over the buffeting waves.

The Church's firmest truth is that fallen man has been extended an unmerited lifeline - redemption, despite our flaws and indifferences. And for an aged wanderer like me, having waterlogged my life with self-indulgent flotsam, rediscovering that unfailing dispensation for repentance is like life from the dead.

The Church, I now realise, is the source from which all lesser spiritualities are mere rivulets and tributaries ultimately tracing back. She is the mountain toward which all my seductive by-roads inevitably ended, the beacon reclaiming me even as I decried her. Hers was the blazing furnace where my ruinous doubts were at last incinerated.

It is to Her, through little pomp and no end of circumstance, that I have circled back after a lifetime's wandering. To the Mater Ecclesiae, my spiritual mother, to whom I owe all and from whom I can, through persistence, find peace.