Dreading September and school

The classroom was an intimidatory place in the days before the abolition of corporal punishment.

Bring on September, the month of shorter days and softer light. The time of year when we return to school; the familiarity of old rooms, the smell of new books. A time when children renew old friendships and mould new ones, wondering where is their place on the Classroom Carousel.

I am reminded of the story of the boy who didn’t want to return to school. He begged his mother not to send him. When she enquired why, he explained that the children laughed at him, the teachers scolded him and that he was terrified of the Inspector.

“Well” said his mother, “You’ll just have to go.”

“Why, why?” sobbed the boy.

“Because” answered his mother, “you’re the Master, that’s why!”

I work in a school these days and I like it, I love it actually, but I didn’t always like school. The line from the Mick Hanly song, , always rang true for me; it was one of my strongest feelings as a child. I grew up on stories of cross teachers and cross dogs. It is little wonder I had a lifelong fear of both. By the way, my fear of teachers has since been dispelled.

My other unhappy memory of my early school days centre around making my First Holy Communion. I was faced into this sacrament when I was six. I didn’t know it then but I had dyslexia and I found it impossible to learn by heart the requisite prayers and the sequence in which they had to be repeated. I always felt that such a lapse was my biggest sin. As a child, I felt that I had somehow sinned again, even before I left the confessional box.

Corporal punishment was prohibited in Irish schools by the Department of Education in 1982. While this effectively ended the practice, the common law defence of "reasonable chastisement" for parents and teachers was not fully abolished until the Children First Act 2015, which criminalised physical punishment of children in all settings, not just schools.

Before 1982, school children were under awful pressure. It seemed that school management, teachers and sometimes, parents themselves, were a force that no child could question. It was a brave child indeed and a braver set of parents that stood up to a system that justified the physical abuse of school children.

A paper by Terry Clavin, (2024), in today’s more enlightened times reads like a fictious tragedy. The following is included in his research.

On February 9, 1954, the published a letter by ‘Catholic mother’ outlining how her nine-year-old daughter had received 13 slaps with a heavy jointer for getting her sums wrong at school. Clavin picks up the story:

Letters either condemning or endorsing corporal punishment in schools poured into the over the next two months, inspiring Constance O’Connell (a.k.a. ‘Catholic mother’) to establish the School-Children’s Protection Organisation. Its goals were modest yet controversial: ensuring a strict adherence to Department of Education regulations stipulating that corporal punishment be administered in primary schools only for grave transgressions, never for mere failure at lessons, and always with a light rod on an open hand. Though these restrictions had existed in some form for nearly 50 years, few people actually knew of them.

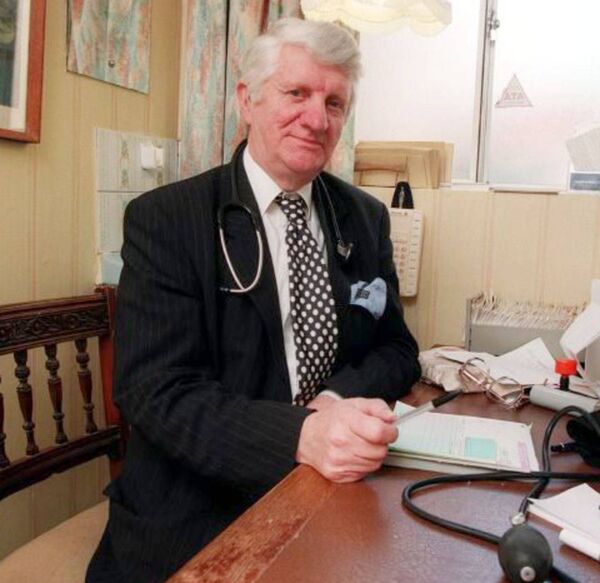

Cyril Daly was a GP in Killester, north Dublin, and a prominent campaigner against corporal punishment in Irish schools. His long campaign against the practice, prompted by his son's experiences, ultimately contributed to the ban on physical punishment in the country. His activism involved writing to church and government officials, and his work was instrumental in fostering a cultural shift against violent discipline in schools. His efforts would eventually bring about the end of corporal punishment in Irish schools.

Daly achieved instant notoriety on November 19, 1967, when the published his imagined description of a schoolboy being hit with a strap by his teacher. Terry Clavin, this time writing in the , describes the content of Daly’s article and gives some idea of the man’s determination and compassion.

I only became aware of Cyril Daly recently. Like all heroes he was, in the early days of his fight for justice, persecuted. Because of brave heroes - and they were brave heroes - like O’Connell and Daly we have a school system today that is filled with kindness and understanding. Which begs the question, is there any other way to educate our children?

Despite some of the brutality described above, this story has a happy ending. People like Constance O’Connell and Cyril Daly have restored honour to our education system. They have helped replace a brutal instruction with a caring learning environment. I see children returning to school at this time of year with smiles on their faces and a lightness in their step. They show respect and frequently express affection for each other… and for their teachers. Changed times. Mol an óige.