In praise of the humble hen

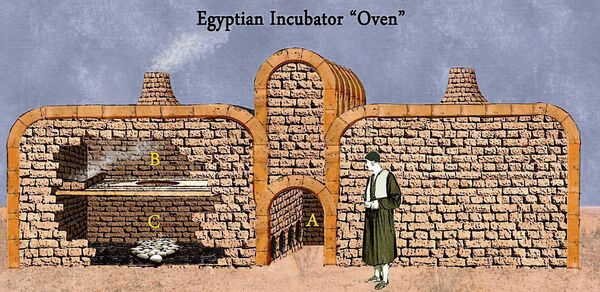

Egypt’s hatching oven incubator, known as Mamals, comprised (A) a central hallway with multiple ‘ovens’ on either side, (B) an upper chamber with firebox to keep eggs warm, and (C) a bottom chamber with fertilised eggs and a small opening to regulate moisture loss.

I was born on a farm. I must say I loved it and seldom a day passes without me drawing on some lesson I learned there. At the same time, I never really felt I wanted to be a farmer. I was happy enough to learn the lessons it taught and move on.

As soon as I got my own place, it was a cottage in the country, I did however feel the need to draw some trace of the farming life around me. I liked the idea of self-sufficiency and having a few chores to do each morning and evening. I found the perfect scratch of my itch in a small flock of hens. Note, I say ‘hens’ and not ‘chickens’, that American term that has crept into our vocabulary in recent times. Here in Ireland, a hen is a hen; a mature bird that lays eggs and a chicken is… a baby.

But back to my flock; from the get-go, I loved them. They were easily trained, matured quickly, were productive and were manageable with a minimum of fuss – sounds like the ideal husband. Their supply of eggs almost came as a bonus, an added extra after all the other good stuff. And so, you might think that is the complete story; done and dusted in two short paragraphs. But you would be wrong because the hens got their claws into me in a way I never expected. It was only the start of a life-long love affair.

It is natural, when you fall in love, to think that you are the only one; the first to experience such a good feeling, but I quickly discovered that people have always had a passion for hens. The simplicity and productive nature of our feathered friend has fascinated farmers, fanciers and food producers for thousands and thousands of years.

The classification of today’s hen (Gallus gallus domesticus) points to its primary origin as coming from the wild Red Junglefowl. Domestication probably occurred about 10,000 years ago in Southeast Asia. The spread of the birds occurred rapidly and was widespread because of their ability to provide meat and eggs without competing with human food sources.

The popularity, and usefulness, of the hen were soon firmly established and so possibilities grew and grew. As the ancient world population began to move from hunting and gathering to living in villages and towns, food production became very important and the hen took pride of place. There were few faster and more efficient ways of providing food for a community than from a hen. You had eggs and you had meat, both full of protein, and a powerful addition to the diet of the Homo Sapien. The only problem, as civilisation grew, was to have enough food to feed expanding populations.

It is the age-old question; which came first, the chicken or the egg? tackled the question in a 2021 article which resulted in the following explanation.

The ancient Chinese and the Egyptians, who had the most mouths to feed, were first in line with bright ideas for increased production. Hens would be needed for meat and egg laying and eggs would be needed to spawn the next generation of chickens and… a growing demand for omelettes! Thus, the circle began to spin faster and expand wider.

Artificial incubation was the key. Hatching eggs by the hundred or the thousand was much better than the ten or twelve eggs a broody hen might produce one or twice a year. But how could such a thing be done without a drop of oil or a unit of electricity in the house?

by Loyl Stromberg is a fascinating encyclopaedia of all poultry-related things. In his book, he gives details of the incubation techniques used centuries ago in China, Egypt and Rome.

Artificial incubation made huge advances with the introduction of paraffin oil, and later electric heat sources, but the humble hen is still the greatest expert when it comes to hatching eggs. Having laid her clutch of fertilised eggs, she will sit on them, almost non-stop, for a period of 21 days. Over her three-week confinement, she will turn her eggs five times every hour. She will magically ensure that the eggs on the cooler outside get rotated to the warmer central position every time. All her eggs will hatch at the exact same time; she actually communicates with the chicks in the eggs to ensure this. Her hatching rate is generally 100%.

The Agricultural Revolution of the nineteenth century saw major improvements in all sections of agriculture, including poultry breeding. From an ancient feral flock of misfits, a special breed with particular characteristics were developed and strengthened. There was now a hen who specialised in laying eggs. There were others best suited to providing meat. There were even new breeds that could do both. Places such as Britain, the United States and Italy were noted centres of progress. Breeds created in these countries remain to this day, although none have the production values of the modern hybrid. Light Sussex, Black Leghorn, North Holland Blue and Rhode Island Red are breeds from this bygone era. They still exist today as treasured heritage breeds, kept and loved by many poultry fanciers. There is even a French hen, the Maran, that lay eggs of chocolate brown… perfect for the third day of Christmas!