Fr Gerry was a devoted priest of the people

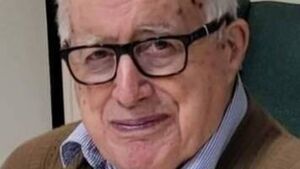

The late Fr Gerry French.

On the morning of Mayo’s All-Ireland final against Dublin in 2013, Fr Gerry French left his home in Ballymun and travelled to the team hotel to celebrate the traditional Mass with the players, a task he has happily performed for every Mayo team playing in Croke Park for several decades. Later that morning, the Claremorris native found himself in Mountjoy Women’s Prison, celebrating Mass for the female inmates, before making the familiar walk to Croke Park, a stadium he first visited as a Mayo minor way back in 1955.

It may seem like a long way from the rustic countryside of Brize in Claremorris to the urban sprawl of Ballymun in north inner city Dublin, but for Fr Gerry a lifetime love of Gaelic football ensured that the bond with his native county was never broken. In his days as a missionary priest in South Korea in the 1960s, Fr Gerry had the posted to him every week so he could keep informed on the ups and downs of Mayo GAA, and later he was instrumental in the development of the John Mitchels club in Birmingham.

The Claremorris man spent his entire adult life away from Mayo, but like so many of his county’s exiles, a fervent passion for the green above the red was always his guiding star. It was that way since the post-War days in the 1940s when he travelled to matches with his neighbour Frank Brett, a Land Commission man who had a keen interest in the affairs of Roscommon football.

“Frank would be going to the Roscommon games so I’d travel with him,” recalled Fr Gerry in an interview with this writer in 2016. “I remember seeing Mayo play Roscommon in Ballina in the first round of the Connacht championship in 1947 when the four Gilvarry brothers were playing and Henry Dixon was at right-half forward.

"Bill Carlos was playing for Roscommon that day and he had a great game. John Noel Carey from Bangor Erris was also there as a young lad and he often used to tell me that Carlos was the best footballer he ever saw. Tommy Hoban was marking Carlos and the two of them had a great battle. Eamonn Boland and Tom Langan had a fierce contest as well and, of course, Pop McNamara, who was a neighour of ours, played for Mayo that day too.”

A Mayo team that included future All-Ireland winners such as Langan, Dixon, Seán Flanagan, Padraig Carney, Joe Gilvarry and Joe Staunton was heavily defeated, prompting a players’ revolution that culminated in the publication of a letter in the in November 1947 demanding a new approach from the county board. The letter had the desired effect and Mayo won the next four Connacht titles, as well as the All-Irelands of 1950 and 1951. Fr Gerry recalled cycling into Claremorris in September 1950 to greet the triumphant Mayo team as they arrived by train with Sam Maguire. Henry Dixon and Jimmy Curran were the two local stars, and the young Gerry French was in awe of Dixon in particular, a colossus both on and off the field.

“Nobody ever knew Henry’s age,” he recalled with a chuckle. “He was in his thirties when he won those All-Irelands with Mayo and he played for Claremorris into his forties.”

Fr Gerry’s football talents blossomed as a student at the local St Colman’s College and he was selected for the Mayo minor panel in 1955. Mayo had a talented team that year and won the Connacht title after victory over a fancied Galway side that included future stars like Mattie McDonagh and John Keely, who would win All-Ireland senior medals a year later, as well as John Donnellan, captain of the victorious 1964 team. Mayo came up against Tipperary in the All-Ireland semi-final, a game Fr Gerry was forced to miss after suffering from hepatitis – then known as jaundice – earlier in the summer. However, he was in Croke Park to see his colleagues lose to the Munster men on a day when the seniors of Mayo and Dublin played out a draw.

By the time the replay was held, Fr Gerry was preparing to enter the Columban Fathers’ seminary in Kilcolgan, his choice of religious order partly influenced by the Columbans’ proud record of achievement on the football field. Des Maguire had been on the victorious Cavan teams in 1948 and 1952, while Peter Quinn was on the Mayo team of 1950-51. In the era of the infamous clerical ban, Columban students seemed to play more GAA matches than clerics from other seminaries around the country so that was good enough for Fr Gerry. He played a lot of football while studying in Kilcolgan and was the founder of a new football team, the Connacht Clerical Students, which comprised student priests from the province who were studying in seminaries throughout Ireland.

“We were sort of an All Stars for Connacht clergy!” he recalled with a warm smile. “We played against all the top clubs in Connacht from 1958 to 1963 and we also played Galway, Mayo and Sligo each Christmas. The team was mainly drawn from the ranks of student priests but we had a few ordained clergy as well, including Fr Martin Newell who trained St Colman’s to win the Hogan Cup in 1977.”

The clerical students played in the Shannon Medals Tournament in Ballina each year on the invitation of Gerard Courell. The games took a lot of organising, especially in an era when methods of communication and transport were worlds apart from those of today.

“I’d be ringing Balla 34,” Fr Gerry recalled. “And I’d send out letters to the lads to let them know when a match was taking place. Brendan Gilligan [whose family owned a shop in South Mayo] was very good to us and he’d borrow his father’s truck to bring us to the matches. Sean McManamon and John Creighton would do the gates with me.”

An ankle injury forced Fr Gerry to abandon his outfield exploits and pursue a new career as a goalkeeper. He played between the posts on the Claremorris side that won the county senior football championship in 1961, a career highlight that became all the more precious following his departure for the missions in South Korea in 1963.

“I went to the All-Ireland between Galway and Dublin in ’63 and then set off for Korea a few weeks later,” he recalls. “It was a huge change going there and it took time to settle in. But there were a lot of Irish priests in Korea at the time and we played soccer together. My first parish priest was an Australian who was into Australian Rules, so that made the transition easier too.”

Not long after his departure, Fr Gerry’s mother came up with the ingenious idea of wrapping the weekly in a letter and sending it to her son.

“It was a great treat and I looked forward to reading about the GAA matches every week,” he recalls. “Korea was quite a military state at the time but the authorities never bothered with it; the paper always got through to me.”

Fr Gerry later moved to America and was in Chicago in 1967 when he heard that Pop McNamara was gravely ill. Still only 46, Pop had moved to the States in the late 1940s, becoming involved in the American GAA scene along with other exiles like the Kilroy brothers from Newport, Padraig Carney and ‘Big Pat’ McAndrew from Bangor Erris. Fr Gerry went to visit his old neighbour in hospital.

“He was reaching the end and the nurse in charge of the intensive care ward told me he was too ill to have visitors,” he recalls. “But I was determined to be with him and I persuaded a nun, who knew me, that I should spend a little time at his bedside.

“As I was standing there, Pop opened his eyes and had what I can only describe as a fleeting moment of clarity. Recognising me, he simply said ‘Fr Gerry, do you think Mayo can beat Galway this year!’”

Mayo hadn’t beaten their old enemy in the Connacht championship since 1951 and the Tribesmen had won their third successive All-Ireland title in 1966. A few weeks after Pop’s death, Mayo travelled to Salthill and dethroned the champions in an 11-point demolition. Pop McNamara had got his wish.

Fr Gerry’s involvement in GAA was rekindled in Birmingham in the early 1970s when he became heavily involved in the John Mitchels club, working alongside his fellow countyman and former All-Ireland winner Dr John McAndrew from Bangor Erris.

“John did Trojan work for the GAA in Birmingham and he played well into his forties,” he recalls. “Like Henry Dixon, nobody knew John’s age. His son Seán joked at his funeral that his father had three birth certs!”

It was a difficult time to be a priest ministering to the Irish community in Birmingham. The devastating IRA pub bombings caused an anti-Irish backlash and left clerics like Fr Gerry facing acute moral dilemmas. When IRA bomber James McDaid blew himself up in 1974, the Bishop of Birmingham George Patrick Dwyer declared that the men of violence should not be granted Catholic funerals. Fr Gerry was utterly opposed to the IRA’s terror campaign but wanted to support his colleague Fr Desmond Gill, who had decided to go against the instructions of the Bishop and preside at the removal of McDaid’s remains.

Fr Gerry found the funeral to be a very upsetting experience. Angry crowds encircled the church and there was a huge police presence. McDaid had left a young widow and three-year-old child behind and Fr Gerry was deeply moved by the poignant sight of these grief-stricken figures. But there was little sympathy in Birmingham for a man who had come to the city to wreak havoc. Airport workers refused to handle McDaid’s coffin when it was being shipped back to Ireland for burial.

“It was a tough time for the Irish in Birmingham but the British people were very supportive too,” recalls Fr Gerry. “They made a distinction between Irish people who wanted nothing to do with the violence and the small group who were perpetrating these terrible acts.”

Fr Gerry later became head of the Irish chaplaincy in Britain before moving back to Ireland in 1984 to take up a post as Chaplain to the Youth Rehabilitation Centre in Rush, Co Dublin. He was also involved in counselling and formation ministry at the Conference of Major Superiors Programme in Dublin over the next 20 years.

He spent two years as a Lecturer in Theology at the Milltown Institute from 1994-1996. Then followed a period of five years back in Britain as Director of the Irish Immigrant Chaplaincy before a final move back to Ireland for parish ministry and later to St Joseph’s Parish, Ballymun.

The new post in Ballymun was a daunting task for a man in his mid-sixties. The inner city community had become synonymous with crime and drugs from the 1970s onwards and its infamous tower blocks were enduring monuments to the failure of successive governments to tackle the thorny issue of urban deprivation. But Fr Gerry’s arrival coincided with a period of urban renewal that has led to a very different Ballymun today. In many ways, the rejuvenation of this once desolate urban heartland is epitomised in the success of local footballers like Philly McMahon and Johnny Cooper whom Fr Gerry knew from their days as students at Ballymun Comprehensive School.

“They are outstanding ambassadors for this community,” he said. “Philly’s journey, in particular, is an inspiration to every youngster in Ballymun. He lost his brother to drugs but managed to use sport to create a very successful life for himself. He now has a couple of gyms in the area and is encouraging youngsters to use sport as a way of improving their lives. I think it is extraordinary and I am thrilled to watch the football success of Philly and Johnny.

“Despite its reputation, Ballymun is a great GAA place. The people love their sport and there is a lot of interest in the Dublin team. James McCarthy and Dean Rock are from just down the road too and play for Ballymun Kickhams, so there is a strong representation from the area on the Dublin team.”

Fr Gerry was chairman of the board of management at Ballymun Comprehensive School for several years, so he saw first-hand the strides the local community made to rebuild itself following the drug scourge of the last 30 years. He played his own small, but not insignificant part, in helping the community to make that journey from darkness into light.

Life took Fr Gerry on a remarkable voyage from Brize to Ballymun, via South Korea, Chicago, Birmingham and London. Throughout it all, his childhood enthusiasm for the green and red of his beloved Mayo never waned: if anything, it grew with each passing year. He had an encyclopaedic knowledge of Mayo GAA and was such an interesting conversationalist who loved nothing better than to reminisce on the many great footballers he saw in the flesh over the years. He was a familiar figure at Mayo Association dinners on both sides of the Irish Sea and was hugely respected by the Irish immigrant community in Britain.

The Columban Fathers, in a tribute to Fr Gerry, stated: "Gerry was interested in people wherever he met them and he never stopped studying human behaviour: he studied Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy at Dublin, Education in Boston, Group Therapy at London’s Tavistock Institute, and Ministry at All Hallows.

"He shared his learning in BA and MA courses at the Dublin School of Psychotherapy, at the Irish Group Relations Organisation, and the Religious Formation Ministry in Dublin as long as his health permitted, even by Zoom during the Covid years.

"Gerry’s interest in people was extraordinary: not only did he remember people’s names, but he could also name their relatives for several generations.

"In England and later in Ireland, he helped a vast number of people, offering an always sympathetic ear and often helping them to find work through his multiple connections.

"He was sympathetic, empathetic and curious to learn about people right to the end."

Fr Gerald (Gerry) French was born in Mayo on August 6, 1937, and died in the Mater Hospital in Dublin on December 12, 2023. He was laid to rest in the Community Cemetery for deceased Columan Fathers in Dalgan Park, Navan, Co Meath.

May his noble soul rest in peace.