The Mayo codebreaker who outsmarted the Nazis

Houses in Dublin destroyed by German bombs in January 1941. Picture: Keystone/Getty Images

The document was already scorched when it reached him.

A handful of blackened scraps, brittle at the edges, carried from a cell where a German agent had tried to burn away his secrets. The war was far from Dublin but its shadow still extended across the city and, in the hush of the Garda Technical Bureau in Kilmainham, under a single lamp, a man set the fragments on glass and began to work.

He wasn’t a soldier or a spy. He was a humble librarian.

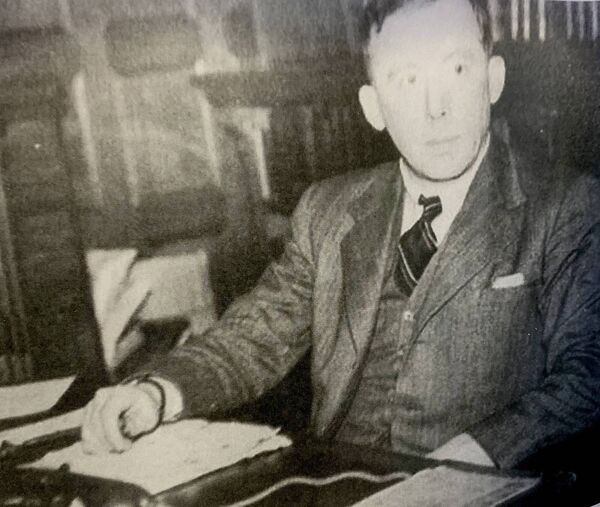

Richard Hayes spoke softly, moved carefully and thought in patterns. For years, his hands had turned the fragile pages of Irish manuscripts; now they hovered over ciphers instead. On the desk before him lay the remnants of Hermann Görtz’s code, the same code that British analysts in London had failed to crack. Hayes dipped a pipette into a faint blue solution, let the liquid fall and waited.

Nothing.

Then something.

A shimmer of colour, the ghost of a letter appearing where only ash had been. One by one, words climbed out of the darkness. He reached for another shard, then another, the way an angler hauls in a net he knows is heavy. Somewhere in Europe, men were dying in fields and skies; here, in a quiet room on a neutral island, a single mind was turning the war ever so slightly on its axis.

Later, when British intelligence examined his reconstruction, they called it one of the hardest ciphers of the conflict to decipher, and admitted they hadn’t solved it themselves. Hayes never boasted about that. He went back to the National Library, sorting shelves and cataloguing books. He was the sort of man who believed that the real work of life, like the real work of war, is best done unseen.

History doesn’t often remember people like Richard Hayes. It remembers uniforms and speeches, not men in corduroy suits who play their part in silence. But for a few extraordinary years, Ireland’s quietest librarian was playing a fundamental role in halting the spread of Nazism.

Although he was born in Abbeyfeale, West Limerick in 1902, he grew up in Claremorris. And it would have been in the South Mayo town, among its quiet streets and slow Sundays that he first learned to notice things, the order of words on a page, the small systems that keep a world from falling apart.

There are no stories of youthful brilliance or mischief, no tales of precocious intellect. His gift, in many ways, was patience. At Clongowes Wood College, and later at Trinity College, that patience met its calling - languages, literature and chemistry.

When Hayes graduated in the early 1920s, the country around him was changing. Ireland was young and uncertain, its archives scattered, its institutions still finding their shape. He joined the National Library of Ireland in 1923, just a year after independence, when the smell of new paint still hung in the corridors of state. The Library was not just a building - it was the young nation’s memory, and Hayes tended to it with the devotion of a man of faith.

Over time, that discipline turned into trust. By 1940, Hayes had become Director of the National Library, a post that demanded both scholarship and diplomacy.

It might have stayed that way - the life of a civil servant, steady and uneventful - if not for the war. Europe was sliding towards madness, but Dublin moved at its own cautious pace: neutral, watchful, outwardly serene. Yet beneath the calm, shadows moved. Messages crossed borders, the Luftwaffe dropped agents into the country, and the small island at the edge of the Atlantic found itself as a crossroads for secrets.

When those secrets needed unravelling, someone remembered the librarian, a man who could see order where others saw confusion. By the time the war came knocking, Hayes had spent nearly two decades learning how to preserve the past. Now, the task before him was different: to protect the present from the future it might become.

Dublin, officially neutral, was still porous. Spies, envoys and opportunists drifted through its Georgian calm like ghosts. A quieter war was underway - one of radio signals, ciphers and names that never made the papers.

It was there that G2, the Irish military intelligence branch, found itself outmatched by a problem written in numbers. They needed someone who could see beneath the surface of symbols, someone patient enough to sit with confusion until it gave up its secrets. They turned to the National Library. And in one of those moments history hides in footnotes, they borrowed its director.

Hayes may have been a man more accustomed to the smell of old paper than the sound of marching boots, but he was nevertheless seconded from Kildare Street to the world of intelligence, thus trading card catalogues for coded transmissions. His colleagues found it improbable, a librarian turned cryptanalyst. Yet in that decision lay a strange kind of logic. Hayes was fluent in pattern.

The test came soon enough. Görtz had arrived in Ireland by parachute and been captured carrying an elaborate cipher. British codebreakers at Bletchley Park had struggled with it; Hayes succeeded. Working through fragments rescued from the agent’s cell, he managed to reconstruct its message, a feat that astonished both G2 and MI5.

His success earned Ireland quiet respect in allied circles and exposed threads of a network that stretched across Europe. But Hayes never spoke of it publicly. The official record remained blank - his reward was silence.

His work didn’t end there. When another agent, Günther Schütz, was arrested carrying what appeared to be an innocent letter, Hayes uncovered a message hidden inside a full stop, a microdot, smaller than a grain of sand. It was one of the first such discoveries in Europe, proof that espionage had entered a new, microscopic age.

Through these years, he remained a civil servant in spirit: precise, modest and allergic to spectacle. To those who met him, he seemed unchanged, the librarian whose great rebellion was against disorder itself. Yet behind that calm was a man who was outsmarting an empire.

In a war of bombs and slogans, Hayes fought with patience. He turned scholarship into strategy, intellect into resistance - and when it was done, he simply went back to work.

No medals, no ceremonies, no coded telegrams of thanks.

He slipped back into the rhythm of the National Library, into catalogues and correspondence, budgets and bindings. It was as though the war had never happened. He never spoke about his wartime work. There were no anecdotes for staff gatherings, no cryptic jokes over dinner.

Over the next quarter of a century, Hayes built a legacy of a different kind. His Manuscript Sources for the History of Irish Civilisation, published in the 1960s, became a foundational reference work. It was as if, having unpicked the ciphers of war, he turned again to decoding his own nation’s story. The project consumed years, requiring the same patience that had once served him in the Garda Technical Bureau. Line by line, entry by entry, he imposed order on chaos.

There were other triumphs too, quieter but no less meaningful. Hayes played a key role in keeping the Ormonde papers in Ireland, protecting a vital archive of the country’s political and social past. He oversaw expansions to the Library’s collections, nurtured young scholars and became a custodian not just of books, but of national identity. For him, the preservation of knowledge was its own form of defence.

When he retired in 1967, he was appointed to the Chester Beatty Library, a post that suited him perfectly: treasures, tranquillity and no public attention. The following years were lived in the same understated rhythm that had defined him all along. When he died in 1976, his contribution to the war effort was still largely unknown.

That was perhaps how he would have wanted it.

For decades, his story remained buried, whispered among archivists, half-remembered by those who had heard rumours of “the librarian who cracked the Nazi code”. Only in recent years has it surfaced again.

In 2024, the National Library of Ireland finally honoured its most secretive director with the opening of the Richard Hayes Room. Among the manuscripts and portraits, there’s a small display describing how he once resurrected a burned cipher using a few drops of ferrocyanide solution and hydrochloric acid. Visitors linger there, surprised by such an act, the stuff of spy novels, which happened not in London or Berlin but a few steps from St Stephen’s Green.

It is tempting to call Hayes a hero, but that feels like a word he would have quietly corrected. He belonged to a generation that believed duty did not require applause. What mattered was the work, not the telling. He spent his life tending to order - first on the shelves of Ireland’s memory, then in the codes of enemies, and finally in the calm after it all.

There is a kind of poetry in that. The man who once made invisible words appear from ash would go on to ensure that Ireland’s own words were never lost to time. He saved the nation’s stories, both ancient and immediate, from the silence that follows neglect.

History is loud. It shouts of victory and violence, of leaders and nations. But sometimes it whispers in reading rooms, in the careful turning of a fragile page, in the slow unfolding of a mind that saw clarity where others saw confusion.

In his quiet way, Richard Hayes proved that contribution isn’t measured by proximity to the front line. Whether in Claremorris or Stalingrad or Iwo Jimo, there is dignity in doing your part and leaving the noise to others.

- If you want to read more articles like this, pick up the , now available in all local newsagents.