Voter volatility can make fools out of polls

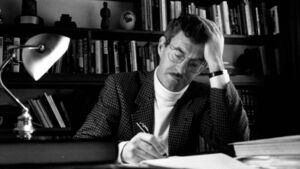

Labour Party leader Dick Spring in his office in Tralee in 1996. The opinion polls did not predict the 'Spring Tide' in the general election of 1992. Picture: Don MacMonagle

Between now and the end of all our upcoming elections, there will be many opinion polls. There will be national polls, European polls, constituency polls. They will fluctuate – as polls do – and they will be watched closely, as polls in Ireland always are. What role will they play in this year of elections? And what do we have to watch out for when they’re used?

As we saw again last week, opinion polls dominate our national political debate far more than they do in the UK. In the UK, it would take a truly seismic opinion poll to become even a significant news story. Here, a poll with any kind of change worth talking about is often the lead item on the news. The ups and downs in the polls themselves are often talked about more than what is behind those ups and downs.

Politicians will deny paying them much attention, but every one of them pays a great deal of heed to the polls. Given that any politician is interested in getting support from the public, it would be odd if they didn’t.

National opinion polls tracking party support are at their most insightful when they reveal a trend over time. But they can’t tell a party how to respond, or guarantee that if they do a particular thing in response, a certain result will follow. Polls about issues can indicate what percentage of people think such and such an issue is important, but on their own they can’t really capture the depth of feeling about it. They can’t tell for sure how a particular policy or initiative would be received. They aren’t a map a politician can use to sail to a destination, for politics is never without wind. And wind – as anyone operating a wind farm will tell you – is uncertain. So while politicians obsess about polls, the wise ones learn from them but don’t steer by them. They know that the headwinds of political debate could force them far off course.

And polls have their limits. Even if they are very accurate, and they are not always, they can only tell you what was going on at the moment in time they were taken. We have recently seen how that can play out in referendums, where public knowledge of a referendum question is usually very low until you get closer to the vote. People tune in just before decision time and often after they have been polled. That is what happened in the referendums on family and care.

That used to be different in general elections. Party support would fluctuate a bit from one election to the other, but established party loyalties meant that the range stayed within broad patterns. A seismic election was one where a particular party broke out of their pre-existing range – what was rare was notable. Fine Gael in the early 1980s. Labour in 1992. Fianna Fáil – not in a good way for them – in 2011. Sinn Féin in 2020.

In the case of Labour in 1992 and Sinn Féin in 2020, neither party detected the surge in their support until it was much too late for them to add on the additional candidates their extra votes would have given them in terms of seats. In fairness to both, it came too late to realise that they could have chartered a bigger boat.

This next general election certainly has the potential to be seismic, and the volatility in public support for parties will be tested by opinion pollsters over the next year. Whether that volatility ultimately affects the ballot boxes remains to be seen. But if I was in the polling business, with everything going on right now, I would be very careful about making big claims about any one poll. We know for example that fewer people say they voted for Brexit than ultimately did. That volatility out there – whatever it is – can make fools of polls, and perhaps those who choose to rely too much on them.

Some pollsters will try and convince you of the respective merits and demerits of their methods and those of others. Some say a poll carried out face to face is much surer than an online one. Differences in results between polls by different companies will be more heavily scrutinised as we get closer to the various elections.

Dáil constituency polls – taken locally and with smaller sample sizes – will be taken and weaponised. In the run up to an election, these are produced by the parties in order to make a convincing case as to why one person or another should run, or not run. They can provide insights, but they can be untrustworthy. If a party official tells a candidate that they shouldn’t run, because an opinion poll has them on 0%, there will be a range of emotions, one of which might well be disbelief.

One of the big problems with constituency polls – even if done genuinely – is that the sample size can be small and – depending on who does it – the quality control might not always be so good. The other thing they can’t do is capture the dynamic potential of a candidate. This is why potential candidates are put through the paces, with a constituency poll carried out every couple of months or so. Our candidate above might go from 0% to 3%, and so be able to argue that they now have unstoppable momentum. The party official will admire their tenacity if nothing else. But you know, tenacity in politics is no small thing.

This election cycle is a little different in that many potential or even already selected Dáil candidates are looking to pile up their votes in the local – or in some cases the European – elections. Real votes in a real election are very hard currency. You can expect a fair few local election candidates to be trying hard to get two quotas, and when they do, they will more or less put it up to their party: run me or lose votes. They don’t have to say it out loud. Two quotas in real votes speaks louder than a mountain of polls.

National politicians will be using their canvassing for the local elections to sense check all the polls that come out. In Leinster House, in every era, there are a few politicians from a range of parties who everyone knows has a deep sense of what they might mean. Their view will be sought by all, particularly if, as we get closer to an actual election, the volatility out there might spark into life in one direction or another.

If there is a sudden surge towards one view or position, and the polls capture it, that itself can then create further momentum. That may well be a big factor in our next general election, whether that be later in 2024 or early 2025. Which raises another question entirely, are we best to ban them during election periods? Perhaps we should poll people on that one.