Church need not fear its sleeping giant

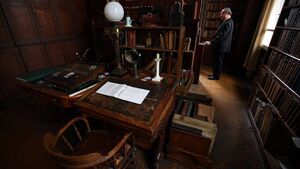

Fr Guy Nicholls, of Birmingham Oratory, stands in the living quarters of Cardinal John Henry Newman which have been untouched since he died in 1890. Picture: Christopher Furlong/Getty Images

John Henry Newman (1801-90) was a famous Anglican clergyman who converted to Catholicism in 1845, was made a cardinal in 1879 by Pope Leo XIII, and was canonised a saint in 2019. At a time when a sometimes bitter and competitive spirit was evident in those who converted (in both directions), Newman became something of a hero for Catholicism, though his path to Rome didn’t always run smoothly.

For example, in 1859, Newman wrote an article, , which was described by one writer as "an act of political suicide from which Newman’s career in the (Catholic) Church was never fully to recover". The then Pope Pius IX was annoyed; the bishop of Newport (Wales) formally denounced Newman for heresy and Monsignor Talbot, the then agent of the English bishops in Rome, called him "the most dangerous man in England".

When 200 laymen wrote to the Catholic Duke of Norfolk defending Newman, Talbot warned: "If a check is not placed on the laity of England, they will be the rulers of the Catholic Church instead of the Holy See (Rome) and the episcopate (the bishops)."

Dismissing the province of the laity as "to hunt, to shoot, to understand", Talbot concluded that "to meddle with ecclesiastical affairs they (the laity) have no right at all". When Bishop William Bernard Ullathorne of Birmingham snidely asked, "Who are the laity?", Newman replied, "The Church would look foolish without them."

Almost exactly 100 years later, the Catholic bishops of the world were leaving Rome after concluding the Second Vatican Council, for which the phrase ‘A People’s Church’ had become a popular summary of its conclusions. So Newman must have allowed himself a quiet smile that the legacy of "the most dangerous man in England" had been so comprehensively validated.

However, Newman had to wait another half a century to allow himself a second smile when Pope Francis proclaimed that he intended to implement the reforms instigated by Vatican Two. Yet, what happened post-Vatican Two in terms of accepting the rightful role of lay people could be summed up in the redolent phrase – "very little if anything at all"– an Irishism that indicates less was happening than was being said was happening.

In the 60 or so years after the Great Council, the Catholic Church was under the extended unsympathetic leadership of the John Paul II/Benedict XVI years. Thus, we discovered the great Irish dancing definition of change (two steps forward and one step back) which soon mutated into its lethal reversal (one step forward and two steps back) to such an extent that, as a Church, we were for a time in danger of reversing into the nineteenth century.

The result was a showdown with what was perceived though never named as ‘the lay threat’. In the words of the late, great theologian, Seán Fagan, the laity became "a sleeping giant whose function was mainly to pray, pay and obey". But the dream, both out of conviction and from need, still lives and a complex of circumstances – from Pope Francis naming unacceptable toxicities like clericalism, misogyny and homophobia to the laity reclaiming their baptismal jurisdiction – the sleeping giant is awakening to what may be a new dawn.

But a more active and determined laity – many of whom are now more theologically proficient and less prepared than heretofore to be dismissed in the manner of Monsignor Talbot above – though fewer than before, are still prepared in significant numbers to exercise their baptismal right and duty to share in the Church’s mission. For some, the lay promise offers what seems like the last great hope for spreading the gospel message of Jesus in the world.

Unfortunately, too, that represents if not a threat at least an irritant to the clerical world. An aged clergy – average age above 70 and climbing steadily – and a progressively weary cohort, though recognising in theory the promise of lay ministry, rightly recognise too the personal challenges facing them, as energy is depleted, work expands as priest numbers decline and issues become more complex as the last great threshold of life hovers in the near distance.

Little wonder that in such circumstances reactions from priests to the rich possibilities for service by a committed laity are less positive than might be expected. Little wonder too that as clergy we become more defensive rather than more relieved or more grateful for the willing and capable hands at the plough. There is even a sense in which we can imagine we are facilitating the necessary change and are open to the possibilities on offer in the transfer from ‘the last priests in Ireland’ to a lay-driven Church.

We are, I suspect, most of us if not all of us to some degree, unaware of our inability to relinquish control and decision-making. It is the result not of individual bloody-mindedness but of absolute immersion in a clerical culture in which we became embedded and which grew organically into a presumption of entitlement, precedent and personal dispensation.

A famous example of that afflicting blindness was a retiring bishop who, in an effort to shape his own legacy, sent his priests a resumé of a long list of his achievements during his extended episcopate.

He concluded, with a grand flourish, that his diocese would have no difficulty introducing synodality as he had already implemented it.

A question for all of us who see motes in the eyes of others but never the beams in our own. (Matthew 7, verses 3-5).