‘We’ll either smash them by this strike or die’

Freedom or the grave... women appeal for the release of detainees on hunger strike in Mountjoy Prison in October 1923. Picture: Walshe/Topical Press Agency/Getty Images

In late October 1923, a letter was delivered to the home of Mrs Ellen McGrath in the heart of Ballina. It was no ordinary letter and the sort which no mother would ever wish to receive. No doubt Mrs McGrath instantly recognised the handwriting of her youngest son Martin Joseph, who had spent the last eight months interned as a Republican prisoner in The Curragh Camp - better known as ‘Tintown’ - in Co Kildare, some 140 miles away.

The hastily jotted letter was brief and to the point. It did not bring good news. Martin was preparing to join ‘The Strike’ the very next morning, and in the event that he would not survive, was taking the opportunity to bid his beloved mother a final farewell.

“Goodbye Mother,” the 26- year old wrote. “Say some prayers for our success.”

‘The Strike’ was, of course, the mass hunger strike of October and November 1923, one of the final acts of the bitterly divisive Civil War that played out a century ago this month. Martin J. McGrath, a veteran of the War of Independence, was one of some 8,000 Republican prisoners who took part in a nationwide campaign of hunger striking in a bid to compel their Free State captors to agree to their unconditional release.

By late 1923, months after the official end of the Civil War, more than 11,000 Republican prisoners - men and women - remained in prisons and camps around the country. Fearing a return to violence, and bolstered by legislation in the form of the Public Safety Act, the Free State government had no intention of simply flinging open the prison gates. Instead, their former comrades would be released gradually, and in batches - judged according to the risk they posed to the fledgling Saorstát Éireann.

There was another way for internees to ensure their immediate release: they could agree to sign the ‘pledge’ - a document - promising allegiance to the Free State and forswearing any attempts to depose it. Few, including Martin McGrath, would ever countenance putting their name to such an oath.

“Our enemies have tried to fool us for too long and break our moral spirit, so we will either smash them by this strike or die,” McGrath wrote to his mother. “The Staters would release me... if I signed their infamous document… if the signing of the document was to be a condition precedent to my release, whenever it does come, it must be unconditional absolutely.”

As the cold and dark of winter 1923 set in, McGrath and his comrades steeled themselves for their final - and arguably most perilous - battle of the revolutionary period, one which would be the ultimate test of their minds, bodies and souls.

Born in Kiltimagh in 1897, Martin McGrath was one of six children born to Ellen (neé Sweeney) and Partick McGrath.

The family lived in Aiden Street, and Patrick - a Galwayman by birth - was employed as a gardener and labourer. The couple had married in 1888 in Ellen’s native home of Ballina. In 1903, the McGraths moved back to Ballina, taking up residence on Garden Street, close to Ellen’s parents’ home. Sadly, Patrick passed away in 1912, leaving Ellen to rear the children alone.

With the outbreak of the ‘Tan War’ in 1919, Martin, like so many young men and women of that generation, would be called upon to play his part in Ireland’s tumultuous struggle for independence. McGrath had already been active on the political scene, campaigning on behalf of Sinn Féin in the historic General Election of December 1918. He joined the ranks of the Ist Battalion IRA, North Mayo Brigade, serving alongside notable figures of the day such as Phelim Calleary, PJ Ruttledge, Stephen Donnelly, Jack Byron and Tom Ruane, to name but a few.

On one occasion he and Ruttledge smuggled quantities of an explosive material used for bomb-making known as ‘war flour’ or ‘cheddar’ on the train from Dublin. McGrath left the package with George Hewson , local pharmacist and prominent brigade member. Hewson would later recall his ‘sheer terror’ when a uniformed Auxiliary entered his premises while the ‘package’ was still in plain sight. Luckily for Hewson, it was a Kodak camera in the shop window that ‘Auxie’ had come to inspect!

As well as taking part in various ambushes and skirmishes, McGrath acted as registrar at sittings of ‘Dáil Courts’ in Ballina - these arbitration courts were an important and peaceful challenge to British authority. In February 1922, he oversaw the official handover of the former RIC barracks on Charles Street (now Walsh Street) to the local brigade. The hugely symbolic occasion was a cause for great jubilation. Certainly, McGrath could not have envisioned that within 13 months, he and many of his compatriots would find themselves imprisoned by their fellow Irishmen, with no sign of a release on the horizon.

On March 1, 1923, McGrath was among a number of high-profile anti-Treatiyites rounded up by Free State soldiers in Ballina and its surrounds. The men were transported first to Galway Jail, then onto their new home behind the wire in Tintown No 2 Internment Camp.

The camp was brought into being by the Prisoners’ Department of the Provisional Government to accommodate the ever-growing numbers of internees. Rows of windowless huts with serrated concrete floors were erected, encircled by high barbed wire fencing. Armed sentries patrolled the perimeter, calling out ‘All’s Well Here’ on the hour, every hour.

Conditions were primitive - the huts were overcrowded, cold and damp. Sanitation was poor and food rations were meagre. The men relied on parcels from home to supplement their paltry diets and no doubt to keep their spirits up. Unsurprisingly, sickness and disease were rife among the men. Frustrated by their situation and worried about what might become of them, keeping morale high was an arduous task. It was against this already bleak background that the hunger strike took place.

Far from being a coordinated campaign, and without official sanction from the Republican leadership, the strike had begun in Kilmainham Gaol on Sunday, October 14, when prisoners under the command of Newport naive and O/C of the Fourth Western Division Michael Kilroy demanded to be treated as POWs, have their conditions improved and ultimately hasten their release. Within days, the strike had spontaneously spread to nine prisons and camps nationwide, including the female prisoners held in the North Dublin Union. Soon, in excess of 8,000 internees had joined the protest - 3,300 in Tintown alone. Martin McGrath was one of eight Ballina men on the strike. He was joined by Pappy Coleman, Denis Sheerin, Pappy Forde, Michael and Jim Walkin, Padraig McAndrew and Thomas Lofus (Bonniconlon).

Castlebar-born Ernie O’Malley wrote candidly about his experience of the strike in his memoir ‘The Singing Flame’.

“I was frankly afraid of it,” he revealed. “I wondered how long I could last.”

O’Malley’s detailed account laid bare the agonisingly gruelling nature of the undertaking - violent headaches, cramps, hallucinations, loss of vision and memory, and intense physical and mental suffering. O’Malley believed that the numbers refusing food were too high and that a small cohort of chosen strikers would have been more impactful. He was proven correct. Within the first four weeks, many came off the strike.

“There was no dishonour for a man to break a strike,” wrote O’Malley. “Hunger-striking was not a fair test anyway, it seemed to attack the spirit more than the body.”

The strike did not have the support of the Catholic hierarchy, who warned that any action of self-starvation would be regarded as a sin - a notable departure from the stance taken during the War of Independence. Newspapers of the day, subject to Free State censorship, carried little news of the strike to readers, vastly curtailing the propaganda potential of the mass action.

On November 20, Corkman Denis Barry succumbed to heart failure and died on the 35th day without food. Two days later, his comrade Andy O’Sullivan died after 40 days on hunger strike. Out of the thousands who had begun the mammoth protest, 176 remained on strike.

Finally, on November 23, Kilroy issued orders that the strike would be ended. The process of bringing the men - many of whom were by now totally unrecognisable - back from the brink began. Ernie O’Malley recalled how food parcels from family members came flooding in, but of course, it would have been far too dangerous to simply begin eating as normal. Instead, a diet of tiny amounts of egg and brandy was rationed at regular intervals.

The ending of the strike was a victory for the Free State, who had stood firm in their resolve to make no concessions to the prisoners. Nevertheless, the problem of what to do with thousands of prisoners, many of whom had varying degrees of ill health, could not be left unaddressed.

As Christmas 1923 approached, the prisoner release schedule was ramped up, and over 3,000 internees could look forward to spending the festive season at home. Among them was Martin J. McGrath.

It would be July 1924 before those deemed the most dangerous, including Ernie O’Malley, would be allowed to walk free.

In the years that followed, Martin J. McGrath established himself as one of the best-known public servants in Mayo.

He served on both the Ballina Town Council for over two decades and as Chairman of Mayo County Council for seven years in total.

At one point he held the record for the number of public boards and committees he was a member of.

Martin knew everyone, and everyone knew Martin. In 1938, he married a local woman who was well-known to him from his youth.

Her name was Ida O’Hora and she was Ballina’s most prominent Cumann na mBan soldier. Coincidentally, Ida had been arrested by Free State soldiers on the same day as her husband-to-be in March 1923. She was transferred to Kilmainham Gaol, and later the North Dublin Union, where she too joined the hunger strike. Her health never fully recovered as a result.

For Martin and Ida, it was a case of ‘opposites attract’.

She was quiet, shy and reserved, whereas Martin was known for his outgoing and colourful personality.

The couple operated a newsagents shop at Upper Pearse Street for a time. Martin entered the auctioneering business and Ida served as Old Age Pensions clerk for the county for many years.

In 1946, Martin established the Ballina branch of Clann na Phoblachta, hosting the party’s enigmatic leader Sean MacBride on many occasions. MacBride, son of Maud Gonne and martyred 1916 leader John MacBride, spent many an evening in the home of Martin and Ida. No doubt the trio indulged in some reminiscing of days gone by - the good and the bad.

Martin contested the 1948 and 1952 general elections on behalf of the ‘Clann’. He was unsuccessful on both occasions - his comrade of old PJ Ruttldge was returned in ‘47, and in ‘52, Pheilim Calleary took the North Mayo seat following the passing of Ruttledge. Martin’s beloved mother died that same year.

McGrath returned to local politics as an independent councillor. In 1966, Ida passed away, and it was only when his own health began to fail that Martin finally slowed down. Interestingly, Martin never applied for a military pension, but in 1970 he sought his service medal, which was duly awarded to him.

He went to his eternal rest on January 19, 1974. His funeral at St Muredach’s Cathedral drew large crowds, a testament to his immense popularity and the esteem with which he was held across the county.

He was laid to rest beside Ida in Leigue Cemetery, where a simple headstone belies the fascinating lives of one of Ballina’s most interesting couples.

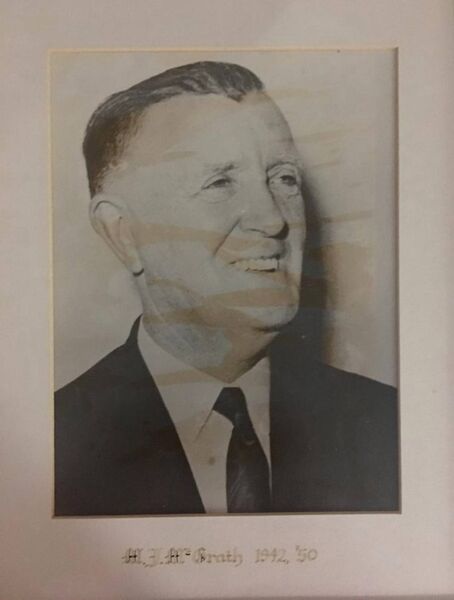

On the walls of Ballina Municipal District Office hangs a striking portrait of Martin J. McGrath - he is smiling broadly and exudes a certain charisma. Few who see it could ever imagine that 100 years ago this month, he was prepared to give his young life for the Republic he held so dear.