The night when death came to a North Mayo fishing village

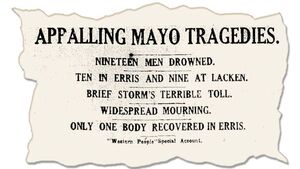

The Western People's coverage of the North Mayo drownings of 1927.

On the night of October 28, 1927, nine fishermen from Lacken were swept to their deaths in one of the worst storms to ever hit the west coast of Ireland. JAMES LAFFEY recounts the dramatic events of that tragic night 95 years ago.

October was coming to an end and the fishermen of Rathlacken were making the most of those fading autumnal days. Rarely had the catches of herring been so plentiful in Lacken Bay.

68-year-old Tom Melia had hung up his oars some 16 years previously but the promise of a good evening’s ‘catchin’ was enough to entice him back onto the calm waters of the bay on October 28, 1927. His sea-faring skills would be put to the ultimate test before the night was out.

Like most coastal communities in the first half of the twentieth century, fishing was a way of life for the people of Rathlacken. Most of the local men were engaged in subsistence farming but it wasn’t enough to keep them - and, more importantly, their families - alive. In an era before multi-nationals and REPS payments, something else was needed to augment the paltry income derived from farming small, unproductive plots of land on the west coast of Ireland - and that something was fishing.

Even men who had professional occupations were forced to take to the waters of Lacken Bay to supplement their weekly wage. James McLoughlin’s father earned six shillings per week as a postman but he also had a share in a fishing boat.

McLoughlin’s boat was one of nine vessels that left the pier at Lacken at around 5.30pm on that fateful Friday evening. The boats were reasonably sturdy affairs, measuring between 24 and 26 feet in length, and carrying crews of eight or nine men. The fishermen tended to stay within the confines of Lacken Bay where they would remain for a couple of hours, spreading their nets for the catches of herring that would be sold at the market in Ballina in the coming days.

Survivors would later claim that the bay was so calm it was like a ‘sheet of glass’ when the nine boats cast off from the pier. But some would say, too, that there were ominous signs on the horizon.

Michael Murray, of Castlelacken, whose father, Thomas, survived the tragedy recalls his father telling him that he met a neighbour, Paddy Golden, on the way to the pier.

“Paddy pointed to the sky beyond the Gazebo [a belfry-type structure on the hill overlooking the Bay] and said: ‘Be careful tonight, boys, I don’t like the look of that.”

Golden was pointing to dark clouds to the ‘far back’ of the sky.

Sam Bourke, father of Robbie Bourke, of Carrowmore House, was thatching oats with a neighbour, John Newcombe, as the boats prepared to depart the pier. Newcombe was to accompany his brother-in-law, Thomas Lynott, on the ‘Rose of Rathlacken’. As he was leaving, Newcombe remarked to his colleague that it was a very calm evening for fishing. Sam Bourke’s response was telling: “It’s too calm and I don’t like it.”

John Newcombe made his way to the pier only to discover that the ‘Rose of Ratlacken’ had already departed without him.

His place had been taken by Thomas Goldrick, a 40-year-old ex-British Navy serviceman, who had fought in World War I. He was asked, at the last minute, to make up the numbers on the ‘Rose of Rathlacken’ as a minimum of eight men were needed for a fishing trip. The veteran of many a naval storm willingly obliged.

One of the last acts of the fishermen as they put out to sea was to remove their caps and recite the ‘Our Father’ as they passed the pier head. At least half of the boats were named after Irish saints, demonstrating the importance of religion in the lives of the fishermen.

The local Catholic Church and Parochial House were only a stone’s throw from the pier and Parish Priest, Fr Michael Quinn, might have even heard the prayers of the men drifting in the calm air on that October night.

Fr Quinn’s house boasted one of the few wireless sets in the locality and he listened to the weather forecast as usual at 6.30pm. The forecasters were predicting an approaching change of weather, probably a storm. But it was too late for Fr Quinn to warn the fishermen of the imminent danger. The nine boats - with more than 80 men on board - had left for the fishing grounds of Lacken Bay an hour earlier.

As darkness fell across the bay, Fr Quinn could do little but pray for the safe return of his parishioners.

***

The nine fishing boats were not that from the shore. In fact, none of the boats was more than 700 or 800 yards from the pier when they cast out their nets for the first haul. They had been at sea for more than two hours when the crew of the ‘Mystical Rose’ became uneasy. The night had grown dark and there was an eerie stillness in the air.

The young skipper of the ‘Mystical Rose’, 29-year-old John McHale, shouted across to the crew in the nearby ‘Rose of Rathlacken’ that he was going to make for the pier. One of the crew members in the ‘Rose of Rathlacken’ replied that he did not believe the night was going to be bad and he would stay out for a while longer. It proved a fateful decision.

The ‘Mystical Rose’ had secured a catch of 500 to 600 herrings and the bulging nets were hauled aboard as the crew prepared to return to shore. It is a measure of the uneasiness amongst the crew on the ‘Mystical Rose’ that they left the catch in the nets instead of emptying the herring into the boat. The wind was blowing hard by now and the crew of the ‘Mystical Rose’ were concentrating all their efforts on reaching the pier.

The boat was within one hundred yards of the pier when the full force of the mini-tornado struck from the south-west of the Atlantic. Chaos ensued on the hitherto calm waters of Lacken Bay. The nine boats were quickly swept apart with the members of each crew left to battle valiantly for their survival. The shouts of the men could not be heard above the roar of the gale as the frail crafts hurtled at lightning speed through the fast-moving water. Several of the boat crews cut adrift their nets, laden with herring, in a desperate attempt to make it to the safety of the pier. The crew of the ‘Mystical Rose’ were almost within touching distance of the pier when their boat was caught by the full force of the storm.

The skipper, John McHale, later recalled that the gale was so ferocious the eight-man crew could make ‘no progress’ against it.

“We were like a cockle-shell on the waters. The wind was so strong that we could not even dip our oars with any effect. We realised that we had no chance whatever of making the quay, and so with despair in our hearts, we tried to make for the strand in the hope that we might be washed ashore, for we could do little to help ourselves. We knew if we were washed past the strand and onto the eastern coast of the bay we were lost.”

The eastern coast of Lacken Bay - on the Kilcummin side - was a death-trap for any sailor. It consisted of a jagged, rocky coastline, with forbidding, stone-faced cliffs that would bludgeon a fishing boat to smithereens within a matter of seconds. McHale and his crew knew their only hope of survival was the mile and a half of strand, also on the Kilcummin side. And, so, the crew of the ‘Mystical Rose’ headed blindly for the strand.

“We struggled, not knowing what second might be our last. The spray from the waves blinded us. Water came into our boat. We baled as best we could, every man pulling his puny best... we thought of nothing but doing our best in our helplessness to reach land anyhow, anywhere, hoping it would be on the soft strand, and not on the terrible teeth of the rocks there beyond. We were nearly mad with fear and despair. And then we struck. I knew it was the strand. And we managed to get ashore.”

The crew of the ‘St Patrick’ - there were actually two boats out that night named ‘St Patrick’ - were in a similar death-battle with the wind and the sea. They too had set the strand as their target but were swept onto the rocks where their boat split her bow and water began to pour in. The eight-man crew scrambled onto the rocks and began to make their way to safety. One of the men, Anthony Kearney, who was lame in one leg, slipped between two ledges in the cliff-face and was lost. The other seven men survived - but only just. John Goulding would later recall that he was under salt water ‘at least two or three times’ before he finally clambered to safety.

Thomas Williams had an equally fortunate escape from the notorious rocks.

“I went down twice,” he recalled, “and when I came up the second time I caught hold of some floating wreckage [from the boat]. The next place I found myself was on the shore, being swept in by a huge wave.”

Six of the nine boats made it to the strand at Lacken on that fateful night. The other three were swept onto the merciless rocks at nearby Kilcummin Head. The crews of two of the three boats miraculously survived - with the exception of the unfortunate Anthony Kearney - but the eight-man crew of the third boat, ‘Rose of Rathlacken’, would perish as their fishing vessel was ripped to shreds against the craggy cliff-face. Their deaths devastated the local community.

***

As the fishermen fought desperately for their lives at sea, their wives and children paced the shore, shouting pitifully into the shrieking wind in the vain hope that they might get some sort of signal from their menfolk. But the howling wind was so deafening that the women could barely hear each other as they stumbled across rocks and cliffs in a frantic effort to catch a glimpse of some sign of life in the turbulent bay. Every plaintive cry was lost on the wind.

Each of the women carried lanterns that flickered feebly on the shoreline as one powerful gust after another bore down on the mainland. Eyewitnesses would later say that they struggled to maintain their balance as they waited helplessly on the shore for the men to return.

It was correctly assumed that the boats would make for the vicinity of the pier and it was here the crowds gathered. No-one believed it was possible for boats to come ashore on the strand at Kilcummin and it was generally accepted that if the boats were swept towards the rocks on the eastern side of the bay the crews would surely perish.

James McLoughlin was five years of age when the tragedy occurred. He lived next door to Patrick Kearney who had accompanied his brother Martin on the ‘Rose of Rathlacken’. James’ father was on one of the other boats that managed to make it home safely.

“Sometime during the night my mother came into our bedroom and she was crying. I cannot remember what she said to us but we knew something was not right. The front door opened and Mrs Kearney [Patrick Kearney’s wife] came in with a storm lamp and she was crying too. She hugged my mother.

“Mickey McLoughlin came in and then Sonny Loughney, both carrying storm lamps. The priest called in about the same time my father came through the door. My father had a bag on his shoulder with herring in it which he dropped on the floor and sat down...”

John McHale and the crew of the ‘Mystical Rose’ had caught a fleeting glimpse of the lanterns on the pier as they battled to bring their boat ashore.

“The poor people ashore were screaming with fear for their sons or brothers or husbands who were out on the water that dark, terrible night,” recalled McHale. “They came out with lamps to aid us in their fear. But that was no good to us in the face of that raging gale.”

McHale later recalled that it took all eight crew members of the ‘Mystical Rose’ to secure the boat on the strand at Kilcummin after it had been swept ashore by a huge wave.

“We had to hold on to her - the whole crew - or the wind would have taken her. Somehow we secured her, and then we staggered home where we raised the alarm. We said we believed all the other boats were lost, and the scene was awful... People came crying to the house all through the night looking for information - people whose friends were out with us, but who couldn’t trace them. I answered them as best I could. It was little enough I could tell them.”

The storm abated almost as suddenly as it had first erupted. By 9pm, the scale of the devastation was becoming apparent to the residents of Lacken and the surrounding villages. The ‘Rose of Rathlacken’ was smashed to pieces and the crew, which comprised the majority of the menfolk from the townland of Rathlacken, had been drowned.

When all hope was lost, the people gathered on the pier and Fr Quinn, raising his hand in the darkness, pronounced absolution for those who had not come home. Among the eight crew members who perished was 40-year-old Thomas Goldrick, the former navy officer who had survived countless sea battles during World War I. The others were Anthony Goldrick (20), Michael Goldrick (34), Pat Goldrick (18), Patrick Kearney (45), Martin Kearney (35), Anthony Coolican (22) and Thomas Lynott (50). The death toll increased when it was learned that Anthony Kearney (36), from the ‘St Patrick’, had lost his life while attempting to clamber to safety on the treacherous cliff face.

For days and weeks after the tragedy, the people of Rathlacken waited for the sea to return the bodies of its menfolk. But the sea did not oblige. The only body ever recovered was Anthony Kearney’s, although there were reports of at least one body being washed ashore in Donegal.

Ten days after the storm, a reporter from the Western People visited the pier and found a woman staring forlornly out to sea. She was Mrs Winnie Goldrick, mother of Anthony, who was the breadwinner for three other siblings, the youngest being six years old. The reporter noted:

“Surely the grieving of that poor mother with her overload of sorrow must melt a heart of stone. I pitied her and watched her as she plodded her lonely way across the sands.”

Many of the surviving fishermen vowed not to return to sea but they ultimately had little choice in the matter. Stark necessity tends to conquer even the worst fears. Life, or at least some semblance of it, resumed in that little coastal community of North Mayo, but it was never the same again.

In 2007, Michael Murray recalled the enormous impact of the tragedy on the people of Lacken; it left an indelible mark on every youngster, including those - like Michael - who were born in its aftermath.

“Sitting around the fire on a ‘Visiting Night’, the neighbours would constantly recall and retell each and every detail as the personal tragedy of so many unfolded,” he recalled. “There was no need for exaggeration in the telling: the anxiety was all too real and too raw, and would remain so for many a long day.

“The tragedy took place at a time before counselling was recognised and it was in the support that people gave to each other by sharing, listening, giving time and attention to the orphans and widows left behind... that was what brought the community through.”

The night of October 28, 1927, was one of the worst ever experienced off the west coast of Ireland. Apart from the nine fishermen who lost their lives in Lacken Bay, ten died off the nearby Inishkea Islands, nine men from Inishboffin and 17 from Rossadelisk in Connemara also drowned, bringing the total death toll in Mayo and Galway on that dreadful night to 45.

This article was first published in the Western People in 2007