The GAA: the organisation for all seasons

Michael Cusack was a teacher and a sportsman, a linguist, a journalist and an astute political observer.

During these weeks of county finals and All Ireland club championships, it is worth reflecting on the presence of the Gaelic Athletic Association in our culture. What is it that is so unique, so effective and so contagious about this organisation that seems more like an organised religion than a sporting body? It seems to be everywhere; it thrives in the rural parishes of the Ox Mountains as well as the crowded precincts of Dublin City.

Is it the link to our ancient games and pastimes? Is it the link to nationalism? Maybe its effectiveness comes from its far-flung network, reaching into every townland in the 32 counties. Maybe it’s the fact that it is run so professionally or perhaps it is the appeal of the amateur game. Whatever the reason, whatever the charm, the GAA has a hold on us and, for the most part, it is a holy and a wholesome relationship.

Before the foundation of the GAA, sporting activities in Ireland were either rough and ready or being taken over by the more formal influence of Britain. They had cricket, rugby and athletics but luckily, at that time, there also remained, in certain places in Ireland, the rudiments of our ancient games.

There was a basic form of hurling and football played by the masses. The former was based on stick and sliotar, the latter was born from kicking a wind-filled pig’s bladder. The Cultural Revival of the late 1800s formed a major part of Ireland’s break for independence from the Empire. It saw the revival of our ancient games as a way to build manliness, pride in our past and ambition for the future.

To assume that the establishment of the GAA was an overnight success would be wildly inaccurate. It had as many birth pains as any nationalist organisations forming in Ireland at that time and its early years were fraught with so much infighting and heaves that its first success was its own survival.

The famous meeting at Hayes’ Hotel in Thurles, which founded the GAA, will show that there was a collection of founding fathers but for my money, Michael Cusack was the daddy of them all. He was a bright, intelligent man with a skin as thick as a buffalo. He was a teacher and a sportsman, a linguist, a journalist and an astute political observer. He was a thickset man, set thickly in his ways, but what a hero!

The Michael Cusack Centre, located in his native County Clare, gives a nice cameo of Cusack and his origins.

Cusack’s passion for reviving our ancient games was uncompromising. His view was that if you were not with him, you were against him… and if you were against him, God help you. At a certain point, this worked against Cusack. He hated the British and he hated the Irish who wished to leave well enough alone. So, Cusack oscillated between being hugely regarded by some and intensely disliked by others. Such was the thickness of his skin, however, that he survived the lot. But his lack of tact did get him into all kinds of hot water.

In a piece written especially for the GAA in 2022 by Damian White, , we begin to see how it was that the GAA took such a foothold, a foothold that still exists to this day.

Cusack was a temperamental man, unafraid to share his opinions in colourful language.

At this point in time, it would have been quite reasonable for Cusack to have said: 'My work here is done.'

Cusack had lit a spark that would eventually burn in every corner of Ireland. That successful recipe contained ingredients that is difficult to analyse. The main meal was a healthy mix of nationalism and parochialism. Add to this a healthy side order of physical fitness and personal ambition, and top off the lot with the spice of local rivalry.

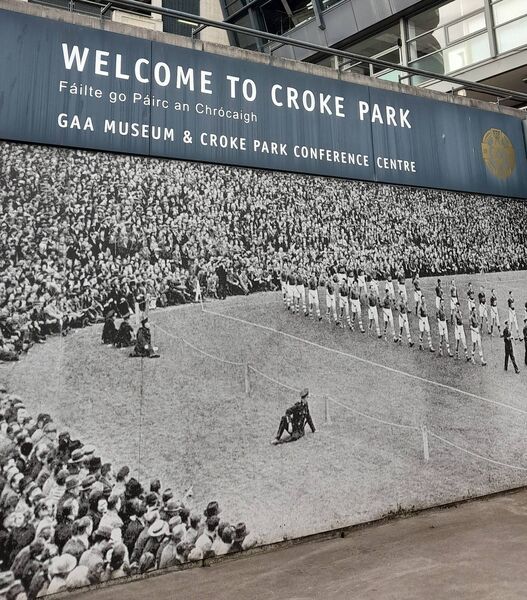

In recent weeks, I enjoyed two very unique GAA experiences. One was a visit to the Croke Park Museum and the other was attending the 2023 GAA World Games in Dungiven near Derry. Both experiences filled me with pride; pride in my Irishness and pride in the GAA.

While taking the Croke Park tour, I fell in with a family from Turin. They were dyed-in-the-wool Juventus fans. When I told them that the Sligo colours were also black and white, we became instant football friends. The thing is with the GAA; wherever you go, there is always connection to be made.

The GAA, writing about their World Games, gives us some idea of the enormity of that project.

If I was filled with pride on seeing the Croke Park Museum, I was utterly blown away by attending the World Games. The organisation of the event, the diversity of the participants, the passion for our native games, were truly amazing. The event was a melting pot of all that is good about Ireland and the GAA.

Great visionaries, such as Michael Cusack, eventually pass on, great players come and go, great teams get consigned to memory, but the GAA itself, it would appear, will live forever.